Navigate:

Commercial hair dye companies are slowly learning a painful secret: “Fast, easy, and cheap” has been beneficial for business for just over a century, but will not be sustainable in the coming decades.

The majority of permanent and semi-permanent hair dyes available in stores and used in salons contain para-phenylenediamine (PPD). PPD, a coal-tar derivative dye, was first used as a commercial fur dye until consumers quickly realized that they could use it on their own hair [1]. PPD-based hair dyes entered the market at the turn of the 20th century. Oxidative hair dyes could be made in a range of colors. The products were easy to use and worked quickly. The color result was relatively permanent. These features made PPD dyes very attractive.

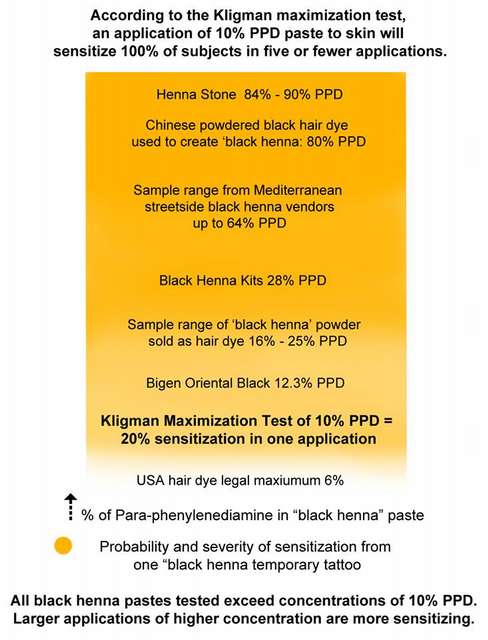

Oscar Wilde was one of the first public figures believed to be sensitized to PPD. Repeated exposures, and/or exposures to high concentrations of PPD lead to sensitization and allergic reaction. This can happen to anyone. As with other allergens, a person can be born allergic to PPD, or that person can develop a sensitivity after exposure. Only about 1.5% of the population is born allergic to PPD. The rest are sensitized through exposure. Kligman’s study showed that 100% of subjects developed a sensitization to PPD after five or fewer patch tests of a 10% PPD mixture [2]. Although sensitization rates vary depending on demographics, country, and gender, conservative estimates say around the numbers are around 6.2% in North America, 4% in Europe, and 4.3% in Asia [3].

The PPD Era

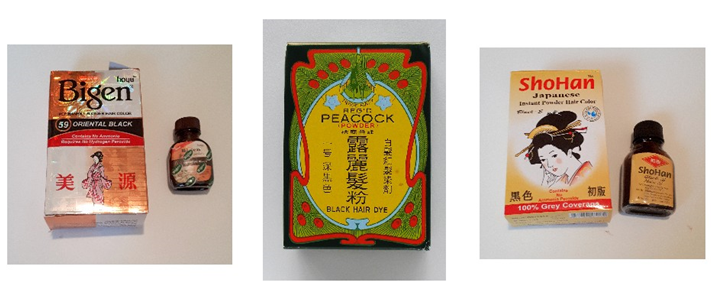

Prior to 1934, there was no restriction on the concentration of para-phenylenediamine allowed in beauty products. It was even in eyelash tints, which led to corneal ulcerations and conjunctivitis [4]. One such product, LashLure, ended up in an installation at the 1933 Chicago world’s fair called “The Chamber of Horrors.” This installation, set up by the FDA, exposed dangerous products. Although doctors, manufacturers, and some consumers were aware of the dangers of PPD hair dyes from the very beginning, they continue to be sold in the United States. While products containing higher than 6% PPD are now illegal, it is still easy enough to find highly concentrated, powdered PPD hair dye products online and in local ethnic grocery stores. Certain countries such as France, Germany, and Sweden have banned PPD products altogether [5].

An advertisement for hair dye from 1885.

PPD sensitization rates have risen. It is projected that by 2030, about 16% of the western population will be sensitized [6]. This means that fewer people will be able to use oxidative hair dyes and other products containing PPD; hair dye companies will see a loss in their customer base. These companies will also see increased reports of injury, and increasing numbers of lawsuits.

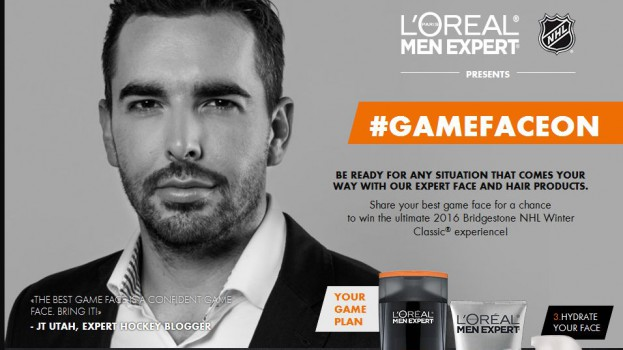

Commercial hair dye companies are now showing interest in returning to a practice that has existed for thousands of years: Dyeing hair with henna and other plant dye powders. For example, L’Oreal recently announced its plans to release a line called Botanea, an all-natural and vegan hair dye line based on henna, indigo, and cassia. Other companies have also produced and marketed henna and plant-based dye products to varying degrees of success.

Whether this “new” return to plant dye powders will be successful to cosmetics corporations will depend highly on the ways they choose to produce and market the product, and how they plan to engage a population which has been dependent on oxidative dyes for so long. Not only will it require these companies to learn the science behind this completely different technique, but to also admit and come to terms with the danger of PPD which they have denied for over a hundred years. Finally, it will also call for the development of henna farms and mills in areas where henna crops will thrive, and the establishment of high standards for exported products.

PPD Sensitization as an Epidemic

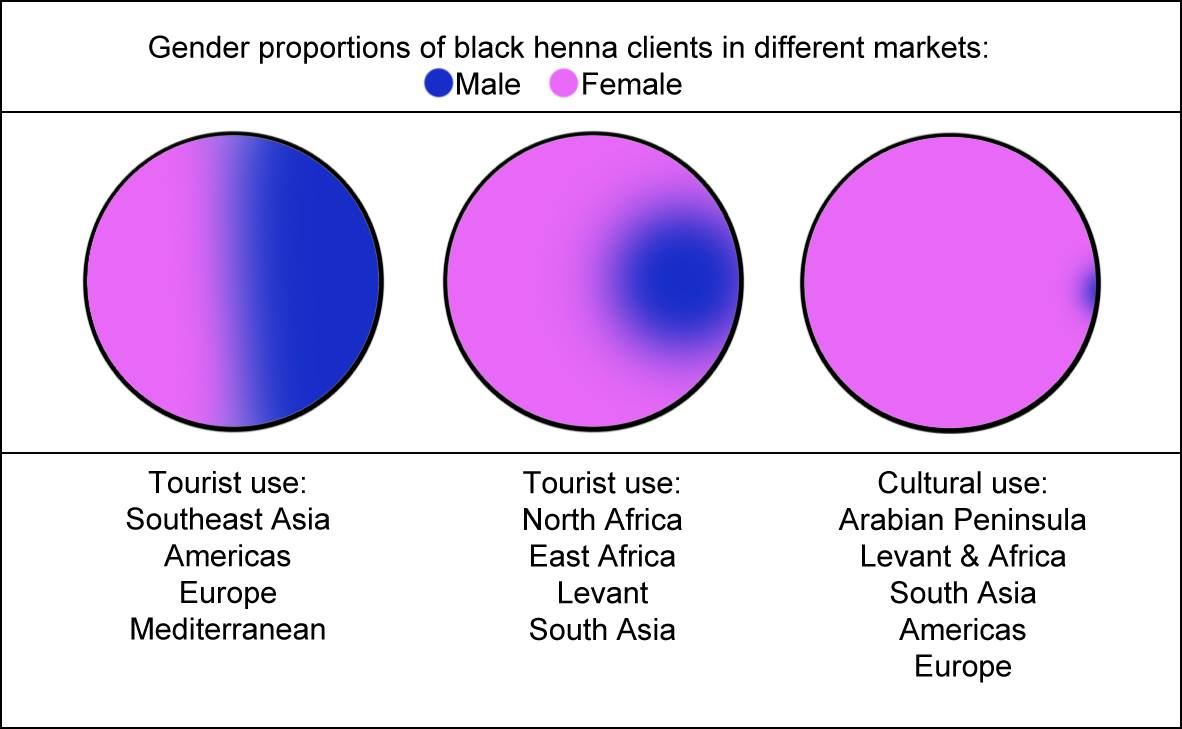

In the past decades, we have seen a rise in the rate of PPD sensitization. Not only are more people developing reactions to PPD, but their ages are getting younger. This is correlated with the popularity of “black henna” tattoos in tourist areas, as well as the increase of young people using hair dyes [7]. Catherine Cartwright-Jones, Ph.D. explores this epidemic in detail in her dissertation, “The Geographies of the Black Henna Meme Organism and the Epidemic of Para-phenylenediamine Sensitization: A Qualitative History.”

“Black henna” is nothing but a concentrated PPD hair dye mixture, applied directly to the skin. Hair dyes in the United States contain up to 6% PPD. These “black henna” mixtures can contain 25% PPD concentration or higher, enough to sensitize a person within one application. The use of PPD on the skin is illegal in the United States, but “black henna” stalls are very common in tourist areas, and the law is not actively enforced.

The practice of using concentrated hair dye to create designs on the skin began in North Africa in the 1970s, and by the 1990s it was popular in western tourist destinations such as resorts, amusement parks, and boardwalks. When a child or young adult gets a “black henna tattoo” while on vacation, then, years later, uses a commercial hair dye containing PPD, they can experience a reaction serious enough to land them in the hospital. To learn more about PPD sensitization, read What You Need to Know about Para-Phenylenediamine (PPD).

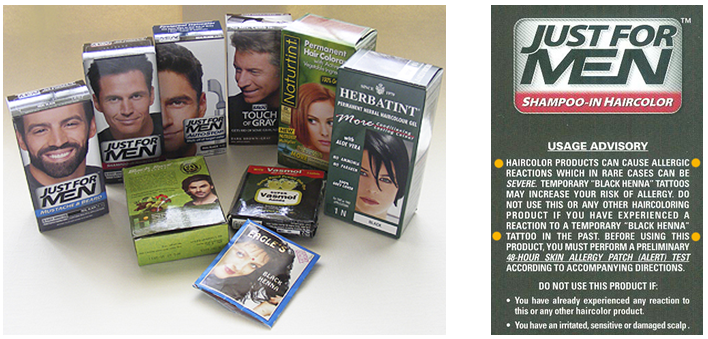

These powdered hair dyes contain concentrated PPD and are easily available online and in local stores despite restrictions.

PPD is also used in printing, the manufacturing of black rubber, and many other industries and products. From the start, doctors and scientists were concerned about the negative effects of PPD and warned consumers of its dangers [8]. However, on November 2, 1934, the FDA struck up an agreement that hair dyes could contain up to a 6% concentration of PPD as long as the packaging contained adequate warning. Since then, the vast majority of permanent and semi-permanent hair dyes sold in stores and used in salons contain PPD.

Here is the exact wording from the FDA:

“What the Law Says About Coal-tar Hair Dyes

Under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), a law passed by Congress, color additives must be approved by FDA for their intended use before they are used in FDA-regulated products, including cosmetics. Other cosmetic ingredients do not need FDA approval. FDA can take action against a cosmetic on the market if it is harmful to consumers when used in the customary or expected way and used according to labeled directions.

How the law treats coal-tar hair dyes:

- FDA cannot take action against a coal-tar hair dye, as long as the label includes a special caution statement and the product comes with adequate directions for consumers to do a skin test before they dye their hair. This is the caution statement:

Caution – This product contains ingredients which may cause skin irritation on certain individuals and a preliminary test according to accompanying directions should first be made. This product must not be used for dyeing the eyelashes or eyebrows; to do so may cause blindness. (FD&C Act, 601(a)) - Coal-tar hair dyes, unlike color additives in general, do not need FDA approval. (FD&C Act, 601(e)).”

What this means is that companies producing hair dyes containing 6% PPD or less, as long as they provide adequate warning and instructions for patch testing, are relatively well protected from injury suits. Despite numerous serious reactions to hair dye, and despite it being well-documented that PPD is a highly sensitizing compound responsible for the vast majority of hair dye allergies, these companies are widely immune to legal repercussions.

Taking The Hair Dye Giants to Court

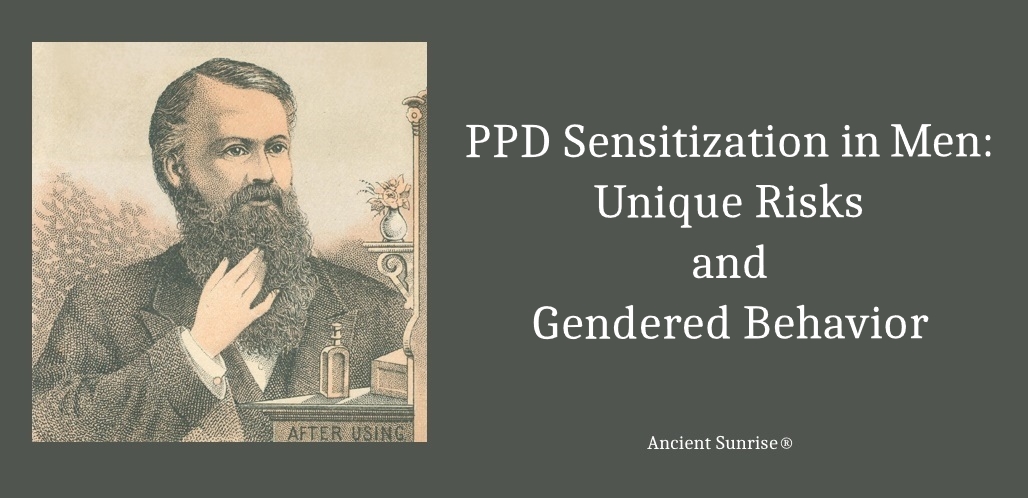

There have been a number of attempts at lawsuits and class action suits against certain companies, such as several recent cases against Just For Men. Those involved in the class action suit against Just For Men believed that the company was intentionally targeting men of color in the marketing of their Jet Black dye, which contained a high level of PPD. Other cases posited that the patch test instructions were not sufficient for properly determining sensitivity prior to applying the dye.

The problem with patch-testing is that PPD often causes a delayed hypersensitivity reaction whose onset may not occur until several days after the test. Most patch tests advise waiting 24 hours. Some people experience no reaction following their first application, but have been sensitized to future reactions. This lack of initial reaction leads to serious consequences when that person, unaware of their new allergy, is exposed to PPD again. Many people who experience severe reactions to hair dye had gotten a “black henna” tattoo earlier in their life. In the case of products sold to men for hair and beard use, a consumer may find that they do not react when conducting a patch test on the inner arm, but experience a reaction on their face, where the skin is thin, sensitive, and potentially abraded from grooming.

The required warning and patch test advisory on a package of Just For Men hair and beard dye.

Lawyers defending hair dye companies have used PPD’s delayed reaction to their advantage, by insisting that there is no way to tell for sure whether the product caused the reaction, if the reaction did not appear until several days after the customer used the product.

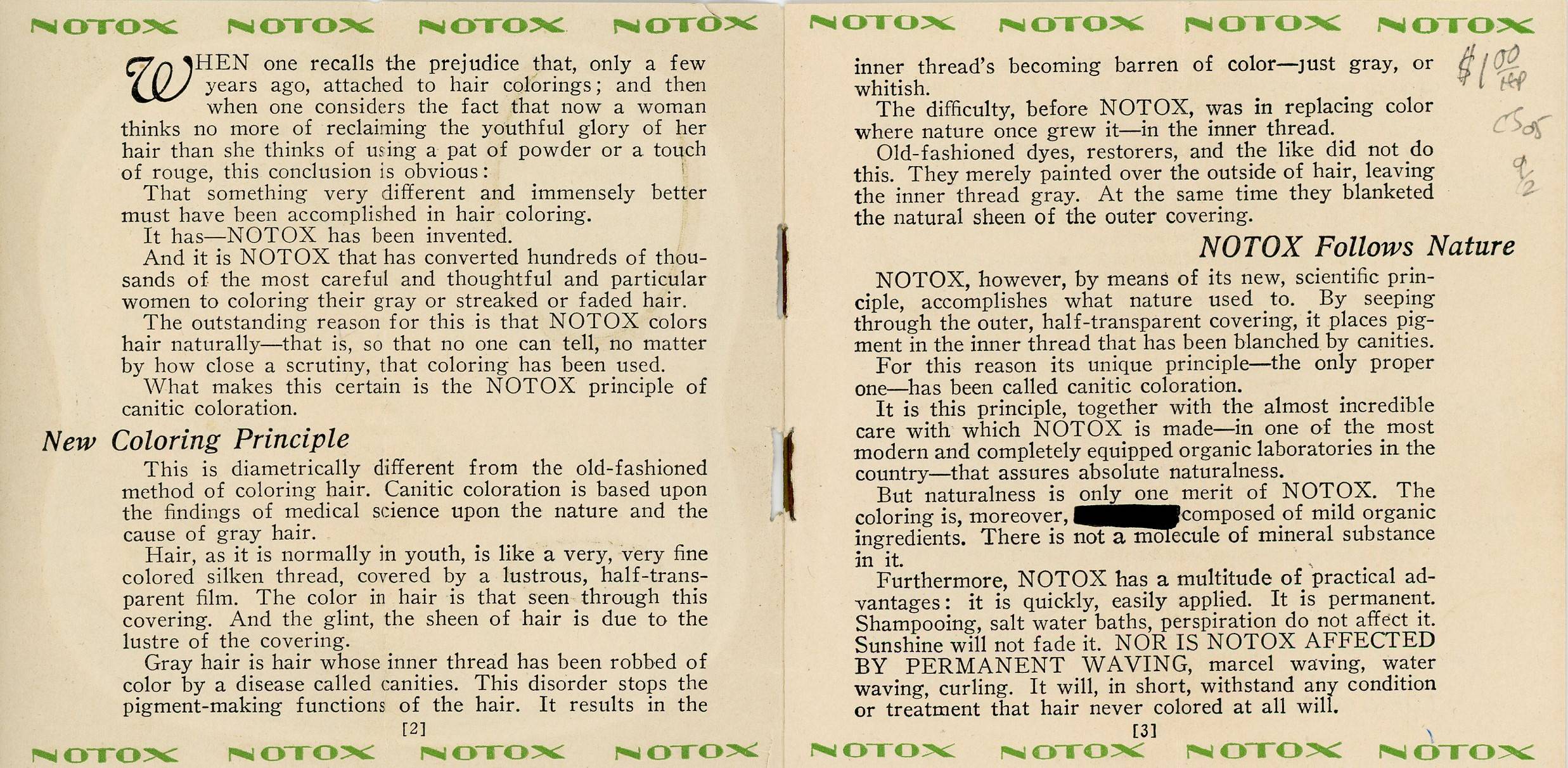

One of the first legal suits against a hair-dye company was that of hairdresser Pauline Karr against Inecto Notox Rapid in 1926. Notox was aggressively marketed as a safe and harmless dye which could be easily applied at home. Despite the fact that companies, consumers, and doctors were already aware of the dangers of PPD, Inecto and other companies did not disclose their products ingredients; at that time, they were not legally required to do so, as the formula was protected as a trade secret.

The dye dripped onto Karr’s finger, staining it black, and she experienced a severe reaction twelve hours later. Karr lost the use of that finger, and sued Inecto. The company won on appeal. Inecto’s lawyers argued that there was no way to prove that the product itself caused the reaction that occurred twelve hours later, and that the company was so large and successful, with thousands of products sold, that there was no way that the dye could be unsafe. Because the company claimed that its formula was the reason for its success, they believed that they were under no obligation to divulge the dye’s ingredients.

This reasoning was used time and time again in following suits. Hair dye companies claim that any injury cannot be reasonably linked to the use of the product itself, and that if any injury does come about from the product, it must be due to misuse on the consumer’s part. Now with the FDA’s stance, hair dye companies are safe from legal repercussion as long as the dye contains 6% or less PPD, and they have adequate warnings on their product labels.

In some rare cases, the plaintiff wins against the company, such as Falk vs. Inecto in 1927. Falk’s lawyer claimed that Inecto Notox Rapid hair dye contained toxic and dangerous substances and that the company was negligent in marketing it as a safe, non-toxic product.

NOTOX “assures absolute naturalness” and claims to be “composed of mild organic ingredients.”

The End of the PPD Hair Dye Era

What commercial hair dye companies are not immune to, however, is a loss in customer base. It is projected that by 2030, about 16% of the adult western population will be sensitized to PPD. 7% of the population will experience a reaction serious enough to require hospitalization [6]. People working in industries where they are regularly exposed to PPD, such as hair styling, fur-dyeing, black rubber manufacturing, and printing, are at higher risk of sensitization. Many hair stylists have had to quit after no longer being able to handle hair dyes. Those who develop a sensitization to PPD have it for life, and will experience reactions to products outside of hair dye, which contain PPD or ingredients involved in cross-reactions.

These companies are not ignorant of the facts. They know that people experience reactions after using hair dye containing PPD. They know that sensitization to hair dye is related to “black henna” tattoos. PPD was named allergen of the year in 2006. Scientists and doctors have long studied the connection between hair dye and contact dermatitis, and delayed-reaction sensitization. Despite this, the beauty industry giants hire their own researchers to put out articles insisting that PPD is safe [9].

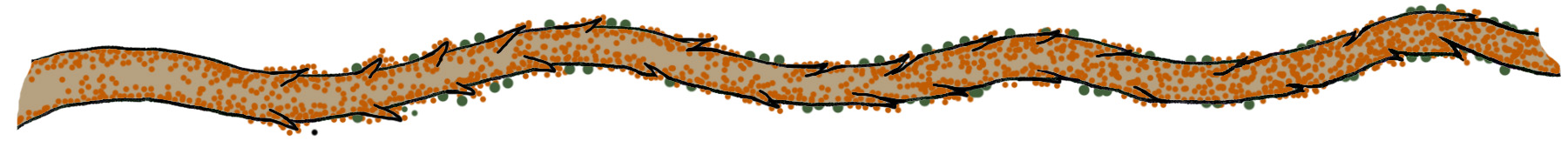

Henna, Cassia, and Indigo plant dye powders have been used to naturally color the hair for thousands of years. When used in the right ratios, these three plant powders can produce an infinite range of natural hair colors, from blonde to jet black. Henna was particularly popular during La Belle Epoque– the end of the 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s. Artists like Toulouse Lautrec painted women with beautifully vivid red hair. Hennaed hair was seen as sensual and exotic.

Henna was upstaged by PPD hair dyes during the mid-1900s, as PPD was cheap, easy to use, and provided fast results. Hair dye companies selling henna attempted to make the process easier for the western customer base by creating compound henna products. These products contained metallic salts and other additives meant to alter the color results and make up for low-quality plant powders. As henna powder imports decreased during WWI and WWII, compound henna products were a way to cheapen the product. These additives had nasty effects, especially when oxidative hair dyes or lighteners were applied over hair that was previously dyed with compound henna. Thus, henna’s reputation was sullied. Henna was associated with dirtiness, backwardness, and brassy, orange hair. Many stylists associate still these negative effects with henna itself, rather than the additives contained in compound henna. The use of pure plant powders as hair dye is not taught in cosmetology schools, while the negative bias toward henna is perpetuated. It is common for stylists to refuse to work on hair that has been hennaed.

But the customer base for commercial hair dyes is shrinking as PPD sensitization spreads. Companies have responded by creating and marketing hair dyes that are “PPD free.” These dyes, though they do not contain para-phenylenediamine, use a molecularly similar ingredient instead, such as para-toluenediamine. Para-toluenediamine is another coal-tar dye within the same molecular family. Is still sensitizing, though less so. Whether a person is sensitive to PPD or PTD, cross-sensitization will still occur. This means that many “PPD free” hair dyes are still unsafe, especially for those who have a PPD sensitivity. PPD sensitivities can also lead to cross-reactions with a number of other materials, such as certain fabric dyes, synthetic fragrances, anesthetics,

PPD also goes by a number of different names. Companies may list para-phenylenediamine under a lesser-known name to make their product appear safer. Here are alternative names for PPD:

- PPDA

- Phenylenediamine base

- p-Phenylenediamine

- 4-Phenylenediamine

- 1,4-Phenylenediamine

- 4-Benzenediamine

- 1,4-Benzenediamine

- para-Diaminobenzene (p-Diaminobenzene)

- para-Aminoaniline (p-Aminoaniline) [10]

Other consumers, whether or not they have a PPD allergy, are simply looking for more natural, or “chemical free” products. We are entering an era in which consumers are more health-conscious, more environmentally-conscious, and more wary of large corporations. People no longer want to blindly buy products, but instead choose to do research, read reviews, and read labels. Companies respond by altering their packaging, releasing new products that appear to be healthier, safer, or containing an exotic, natural ingredient. However, there is no regulation on words like, “natural,” or “pure.” Just because a product contains a natural ingredient does not make it any safer. In the same logic, one could add a plant extract to antifreeze and call it “natural.”

An old shampoo advertisement marketing new “exotic formulas.”

Certain cosmetic companies are now looking into attempting what Ancient Sunrise® has done for years: providing pure plant powder hair dye. If done correctly, this change can be a win in the battle against PPD. But the emphasis is on correctly. We have already seen what happens when henna is manipulated with additives for the sake of “cheap and easy.” Henna does not work well with short-cuts. If these companies wish to be successful, they must take the time to understand the art, science, and culture of the natural hair dye world. Failing to do so will result in a waste of time and resources, and potentially an additional blow to the reputation of henna for hair.

What Must Happen For A Successful Transition

Here is what cosmetic companies will need to understand in order to bring henna for hair into the mainstream market:

1. Henna Has its Own Science That Cannot Be Messed With

In their attempts to sell henna, the biggest mistake that commercial hair dye companies fall into time and time again is their attempt to make it quicker and easier to use. They assume that western consumers want simple, quick-fix solutions and are incapable of using a product that requires too many steps.

We have seen the damage that compound henna products have done, both to the hair of the consumer, and to the reputation of henna. Adding metallic salts to henna will not work. “Henna” products that are sold as a liquid or cream are anything but henna. They may contain some henna (or henna extract, whatever that means), but it is unlikely that the plant dye is doing much of the work. Many of these products contain commercial dyes, either coal-tar derived, or azo-dyes. Any natural plant ingredient is there to make the product seem healthier, whether or not the ingredient is even necessary or useful in hair dye. All of the exotic oils, dried flowers, and cocoa powder in the world cannot fix a formula based on bad science.

Because there is no regulation on what can or cannot be called “henna,” these products are extremely misleading to the uneducated consumer. To read more about products claiming to be henna, read Henna for Hair 101: Body Art Quality (BAQ) Henna, Compound Henna, and Hair Dye That Really Isn’t Henna.

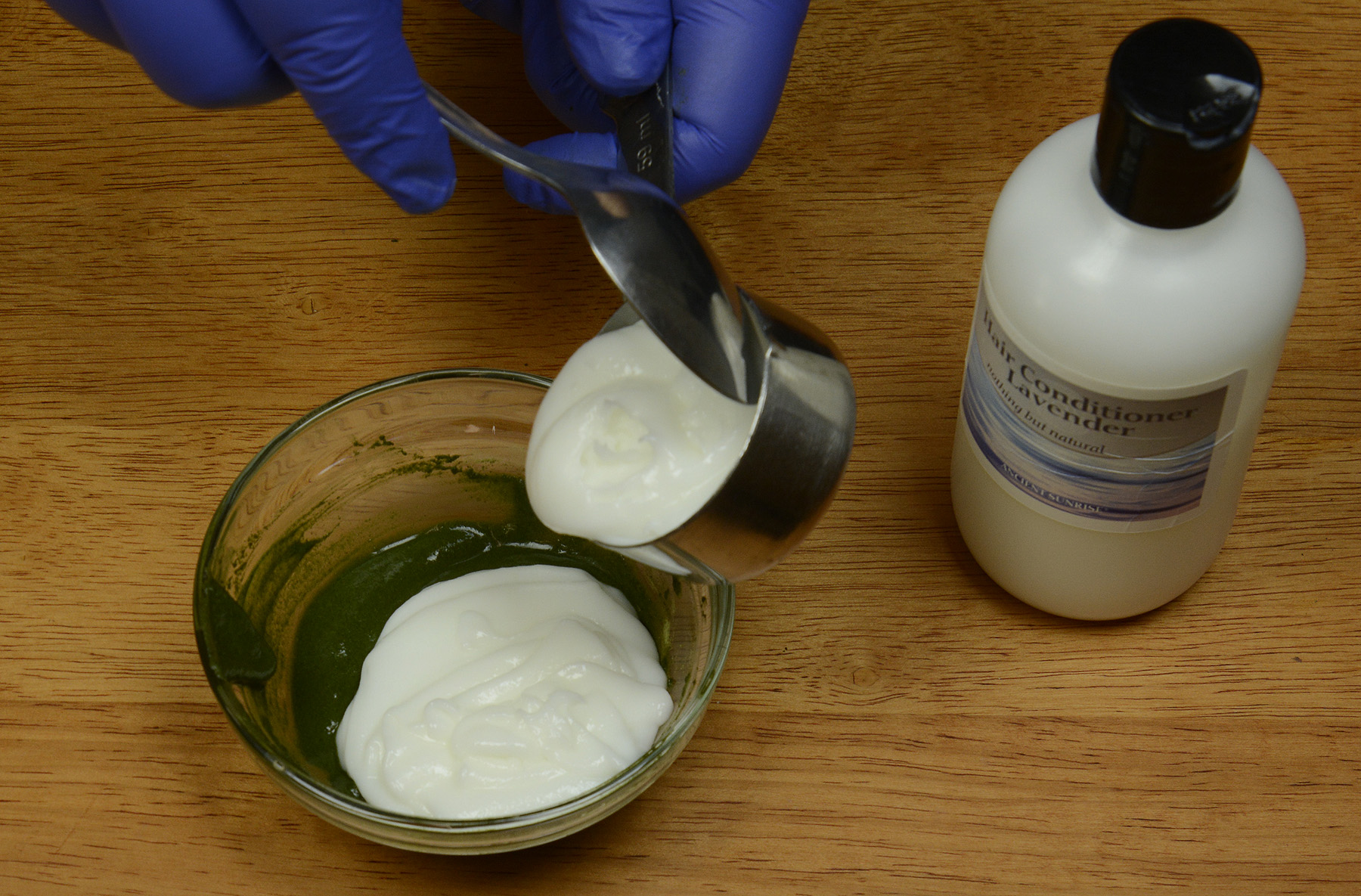

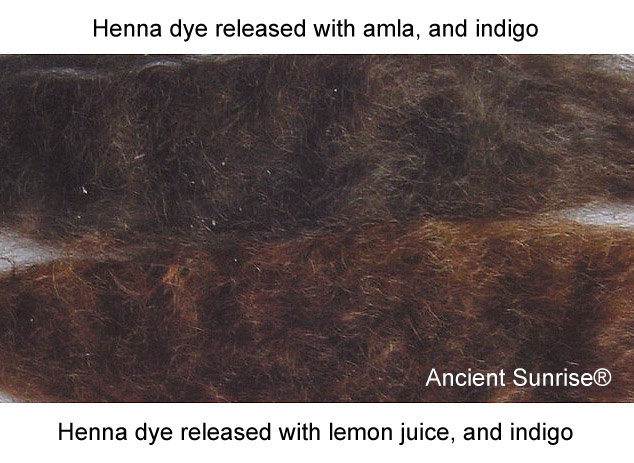

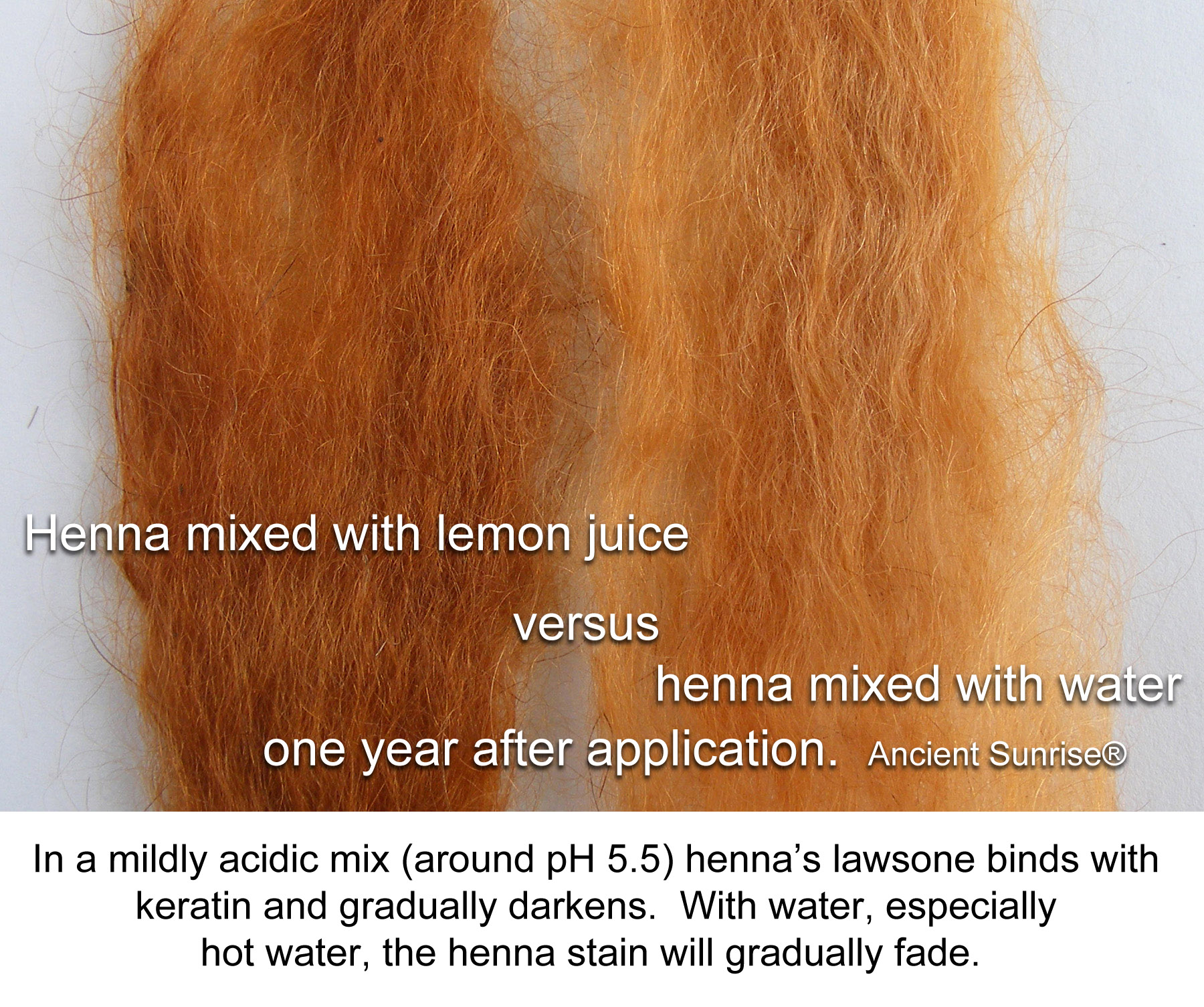

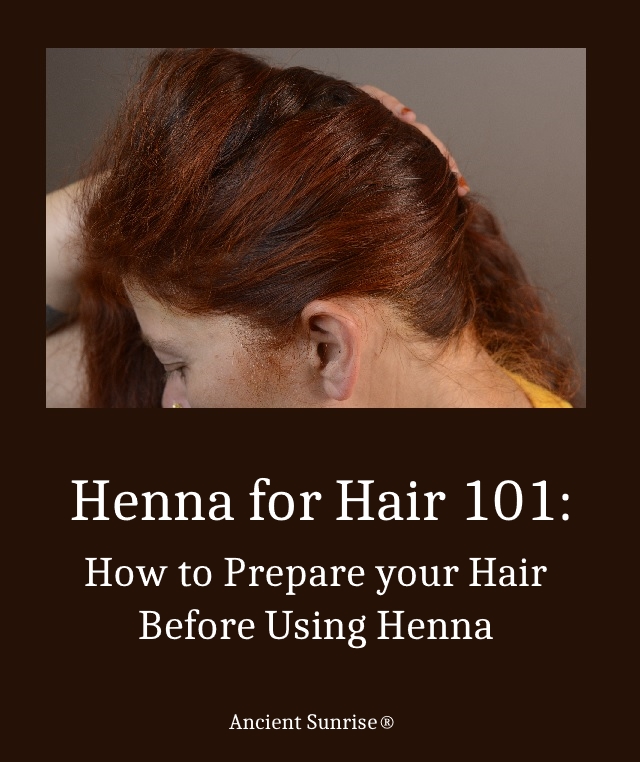

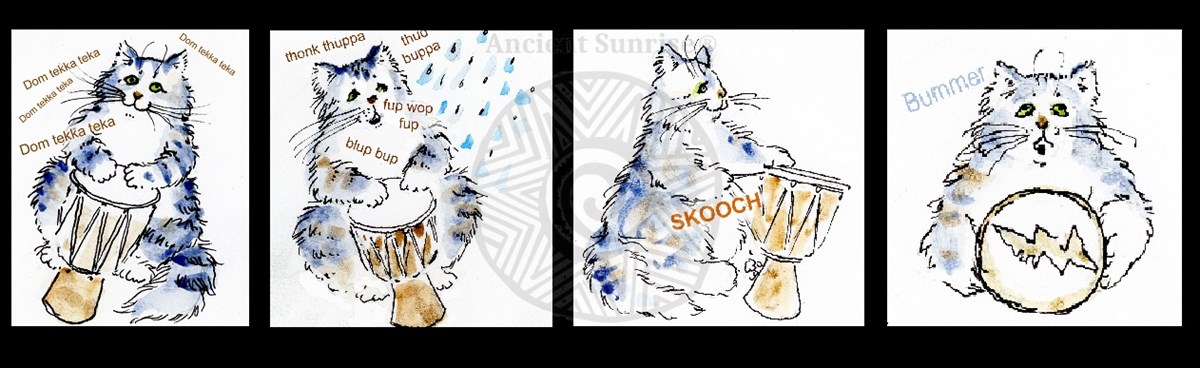

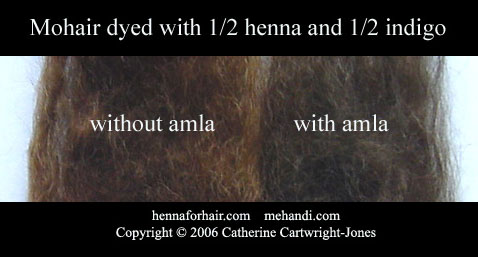

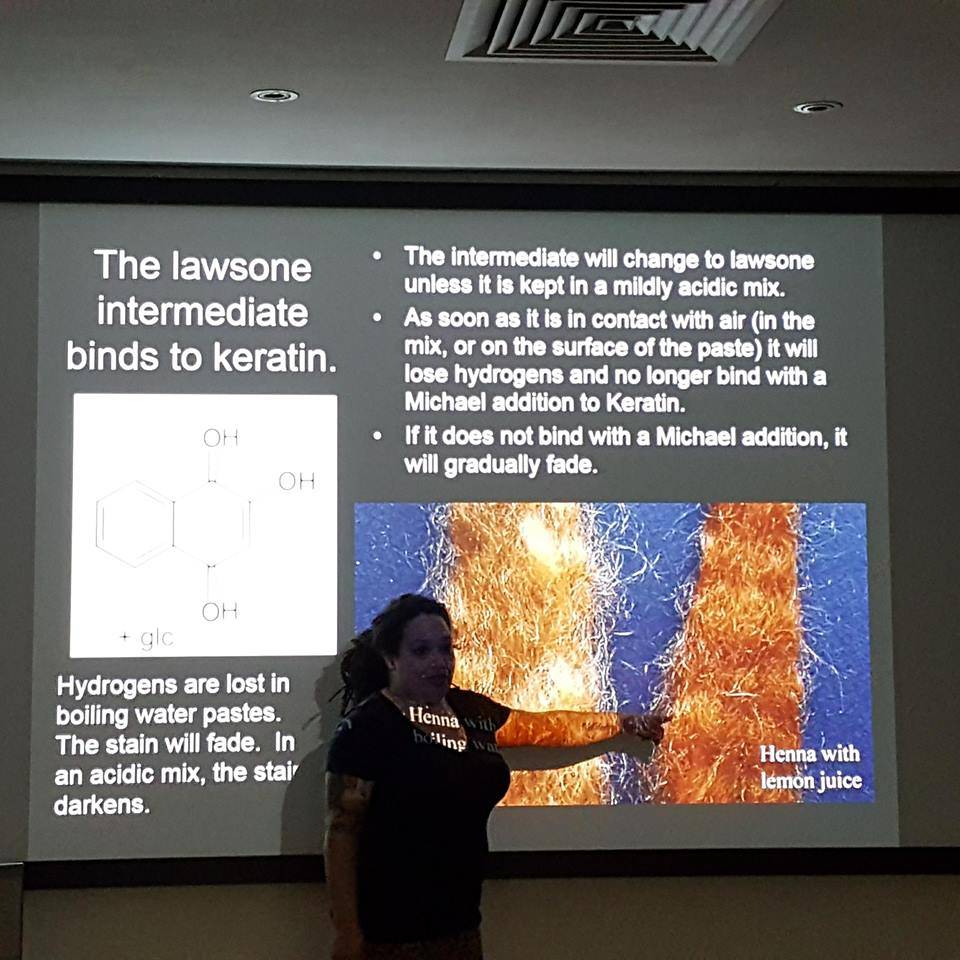

Other companies sell pre-mixed powders containing henna, indigo, cassia, and other plant ingredients all combined into one. These products may recommend mixing the powder with hot water. This will not work because henna and indigo require different dye-release processes to work effectively. Henna must be dye-released with a mildly acidic liquid and left at room temperature for several hours before application. Indigo must be mixed with a neutral or slightly alkaline liquid, and used right away. Thus, a pre-mixed product mixed with hot water will yield undesired results, and fade rapidly.

Some companies offer oil-based “bars” that contain henna and other plant dyes, and are meant to be mixed with water and melted down. Again, these products are an example of bad science. Oil prevents the dye molecules from binding to the hair shaft. The result is, again, far from the desired color and quick to fade.

Plant dye powders cannot be mixed. Extra ingredients, either “chemical” or “natural,” are not necessary. The process cannot be sped up. Cutting corners leads to inferior results. Companies must understand that if they want to bring henna and natural hair dye back to the market in an effective and successful way, they must accept that consumers are capable of and willing to learn the science. Ancient Sunrise® has been doing this for years. Its customer base continues to grow. By providing well-researched resources, attentive customer support, and pure, unadulterated plant dye powders, Ancient Sunrise® has built a community of educated consumers who enjoy healthy, PPD-free color.

2. Henna for Hair is Highly Individualized

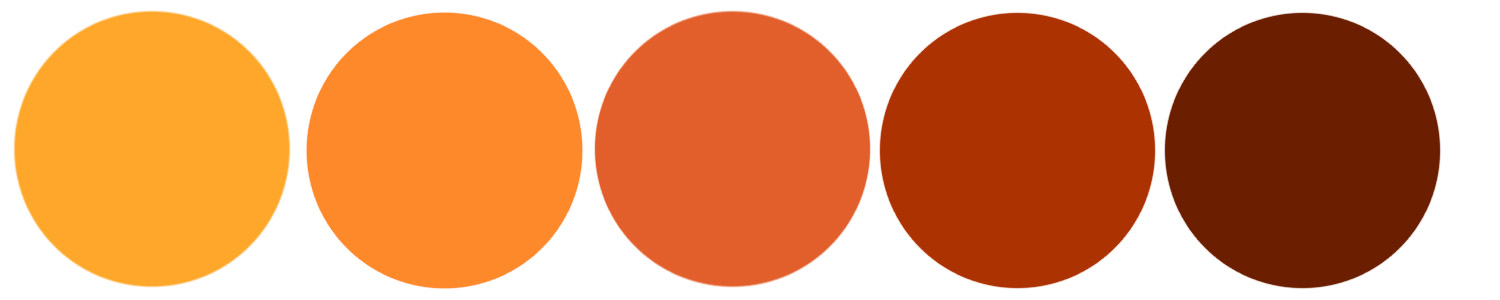

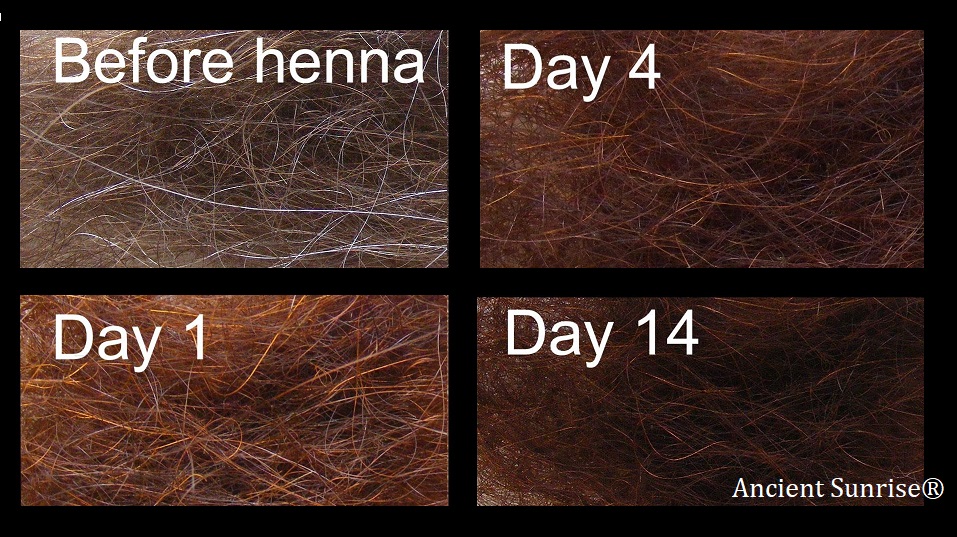

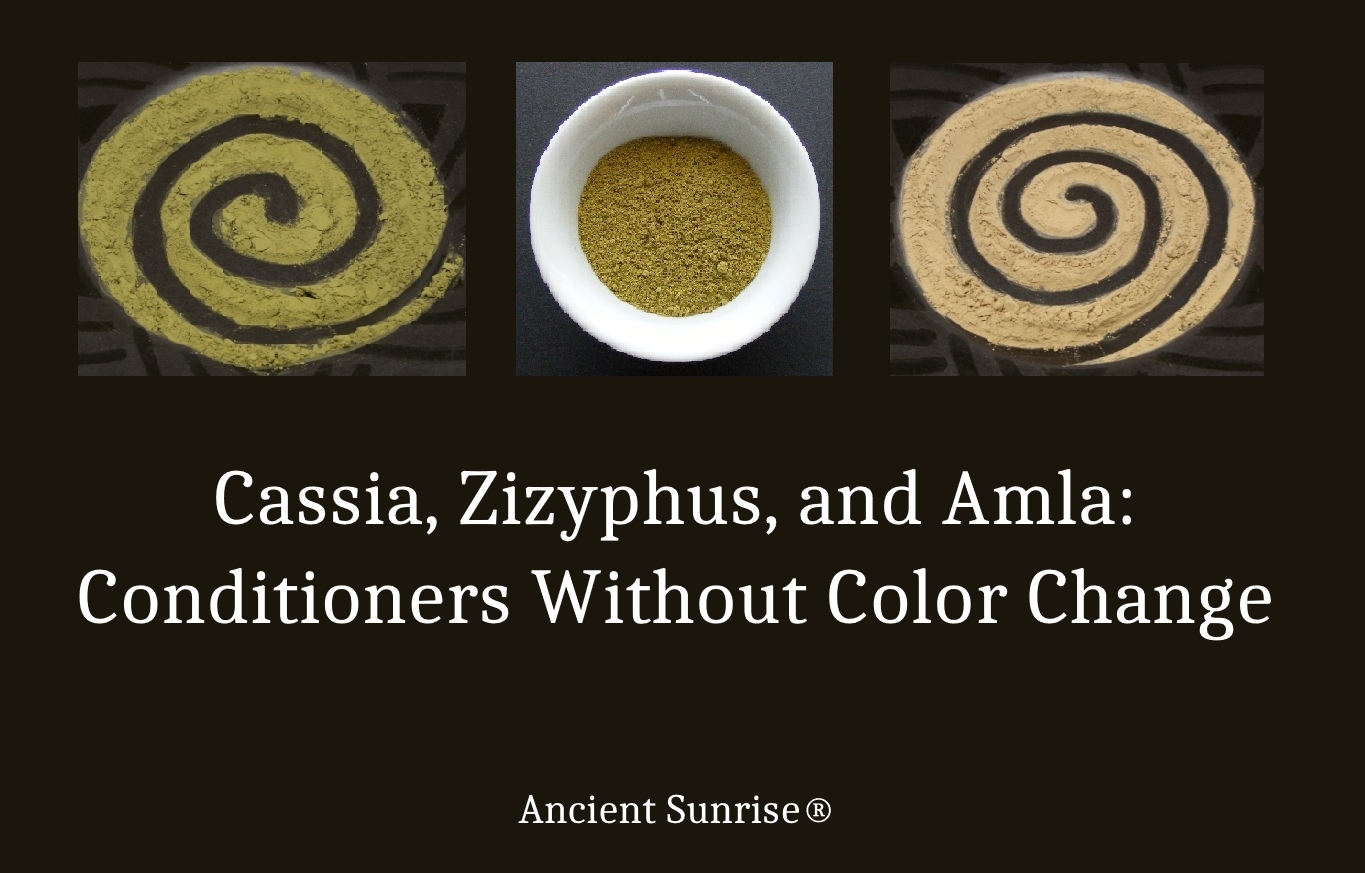

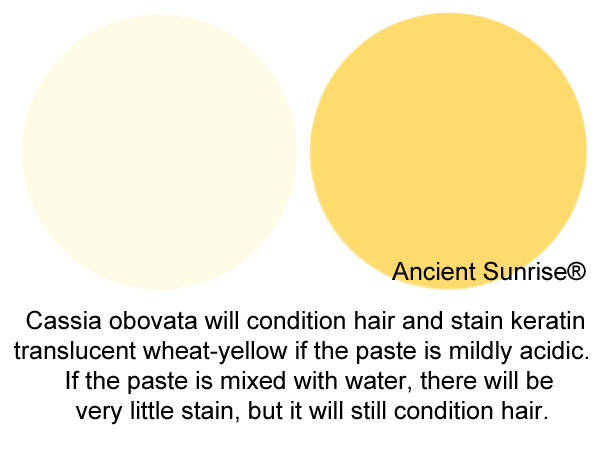

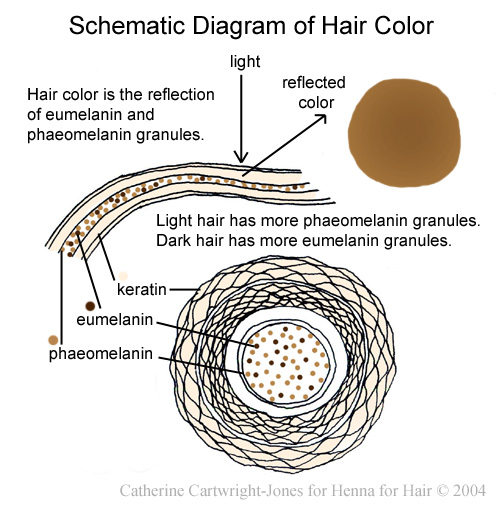

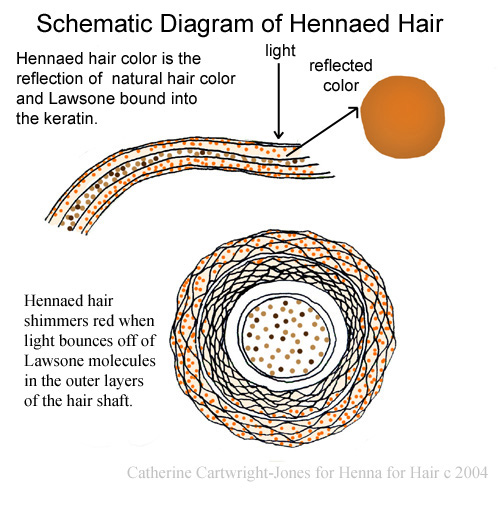

It will not work to force henna for hair into a one-size-fits-all model. Henna, indigo, and cassia all create a translucent stain on the hair. Unlike oxidative dyes which can lift the hair color with ammonia and peroxide, plant dyes cannot cause the hair to be any lighter. Thus, the result is highly dependent on each person’s initial hair color.

Other factors such as a person’s hair texture and condition, body chemistry, local water supply, and personal lifestyle may also affect color results. Therefore, it will not work to slap a color swatch onto a package and claim that that is the result a customer should expect. While many henna-users achieve their desired results within the first or second try, others will need to adjust their recipes and techniques until they find what works best for them.

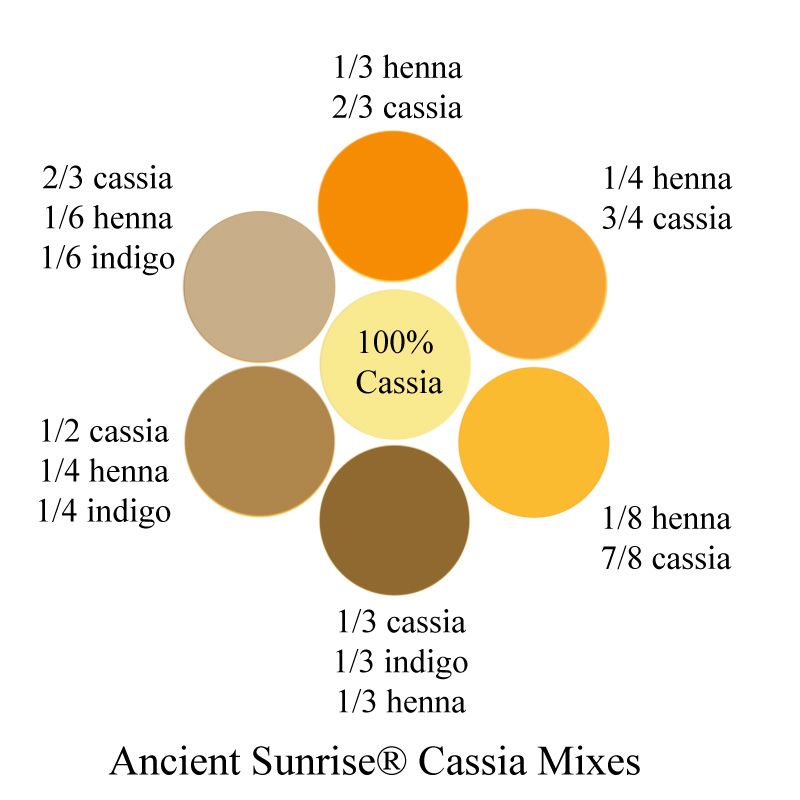

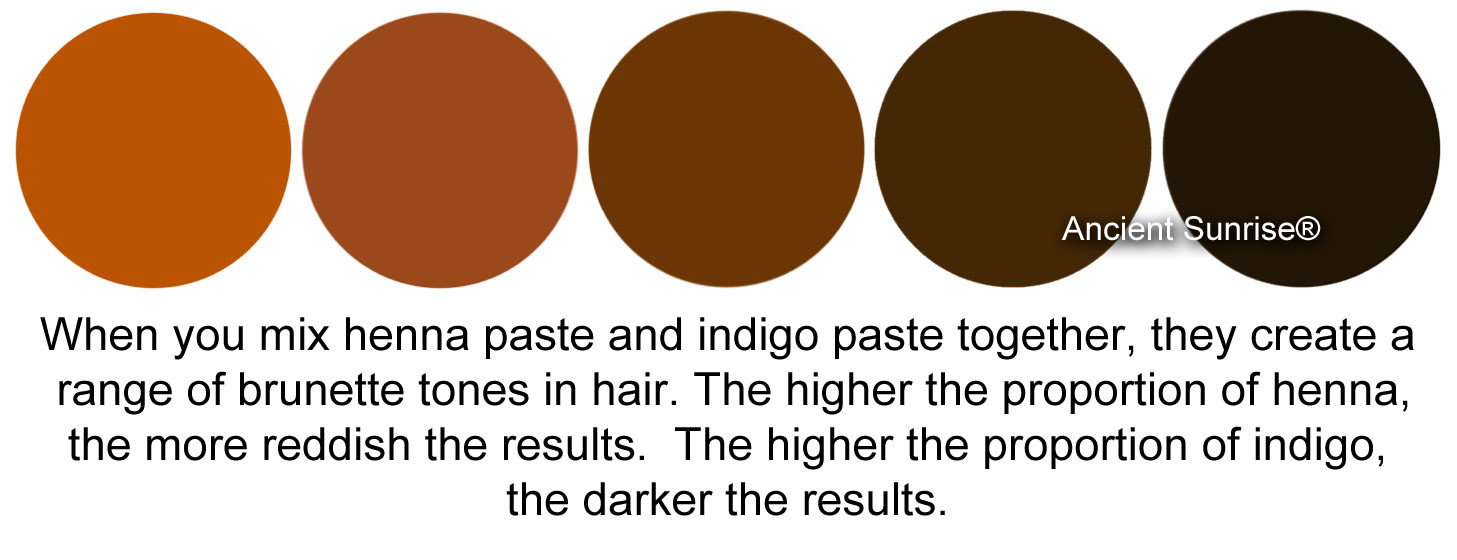

Henna is at the center of most natural hair dye mixes. Alone, it stains light hair red, copper, or auburn. Indigo is used alongside henna to create brunette shades. It can also be applied separately after henna to dye the hair black. Cassia adds golden tones and is the primary dye in blond mixes. To learn more about plant dyes for hair, read Ancient Sunrise® Chapter 5: Plants that Dye Hair.

Off-the-shelf home hair dye kits normally contain two or more bottles containing liquids that are to be combined and then applied. The process does not require much thought on the part of the customer. Henna for hair, on the other hand, involves combining up to three types of plant dye powders in a specific ratio to achieve a certain color. These powders must be packaged individually. When companies try to create henna-based products that mimic the easy application process of commercial hair dyes, the results are inferior.

Ancient Sunrise® Henna for Hair kits provide individually packaged plant dye powders at the correct ratios to achieve a wide range of natural colors.

Because individual differences add so many variables to hennaing hair, both companies and consumers must be aware that it takes patience and communication to achieve the best results. If a customer simply picks up a henna for hair product off the shelf, tries it, and doesn’t like the results, they may never try henna again. They might never know why it didn’t work the way they wanted it to, and what they could have done differently to get the result they wanted.

This is why it essential to create a community of knowledgeable henna-users, and to have this community become part of the mainstream hair and beauty culture. Such communities exist for African-textured hair, for people who grow their hair long, for people who abstain from commercial shampoos, and so on. The Ancient Sunrise® Henna group on Facebook is very active and has over 3750 members. This number increases daily. In this group, members share before and after photos, ask questions, and guide each other. When a question is particularly specific or complex, the Ancient Sunrise® customer service representatives act as the “experts”. They are trained in the science of henna for hair in such a way that they can create individualized mix recipes and offer advice, based on an assessment of a customer’s desires, troubles, and hair history.

Henna for hair is not possible without this kind of support system. Hennaing one’s hair was once common knowledge. Now, people may perm, bleach, and color their own hair at home using store-bought products, but they are largely unfamiliar with mixing and applying plant dye powders. Hair stylists have always functioned as ambassadors between the professional world of beauty, and the day-to-day consumer. If henna is to be successful, it will need to be taught to hair stylists in the same way oxidative dyes are taught. The bias against henna must end, and be replaced with more accurate information. If not, misinformation will spread and distrust will grow between stylists, and consumers who have chosen to switch to henna. The following section will suggest ways in which stylists can become leaders in the switch to plant dyes.

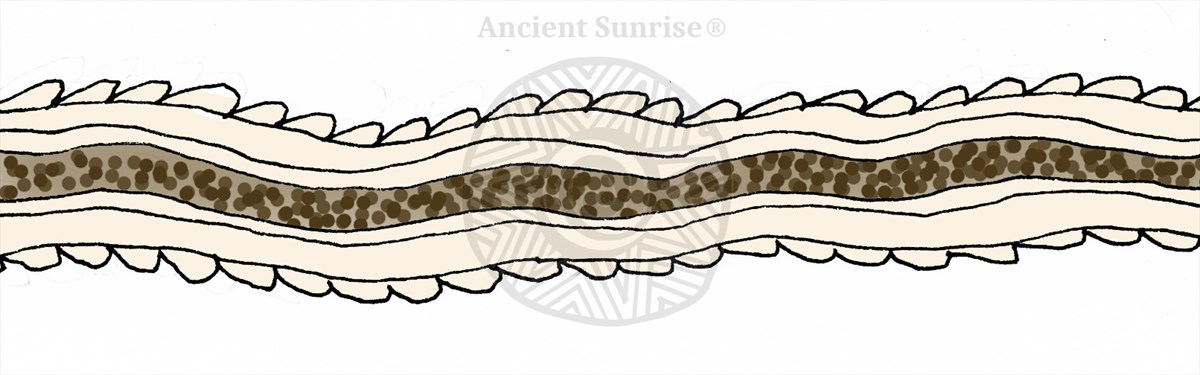

3. Changing the Culture Should Start with Stylists

Henna’s bad reputation continues to live on through the misinformation taught to and spread by hair stylists. This is not the stylists’ fault. Cosmetology texts contain the same out-of-date information in regards to henna that they have for decades. Cosmetologists come to know this misinformation as fact. The dangers associated with henna come from compound henna, where the culprits are metallic salts, not the henna itself. Compound henna products are, indeed, an absolute nightmare for the hair. Now, many stylists still believe that henna damages the hair, that it coats the hair and makes it brittle, and that the hair cannot be lightened once hennaed. In reality, henna is much safer and healthier for the hair. Oxidative dyes use chemicals to break past the keratin cuticle to deposit dye and to destroy melanin cells, thereby weakening both the internal and external structure of the hair strand [11, 12]. Henna, indigo, and cassia deposit dye that binds to the keratin at the outer layers of the strand, leaving the structure not only intact, but reinforced.

Time and time again, Ancient Sunrise® henna for hair users report that their stylists react negatively upon hearing that they use henna. They will scold their clients and try to persuade them to stop. Some stylists will refuse to work on hair that has been dyed with henna. This is understandable; because of the lack of regulation on products labeled as “henna,” it is nearly impossible to determine if the product the client previously used was truly safe, or whether it would react with other chemicals. While Ancient Sunrise® plant dye powders are all subjected to rigorous lab tests to ensure purity and safety, the same cannot be guaranteed by other brands.

Many stylists, however, see the wonderful color and condition of our clients’ hair and begin to develop an interest in henna. Several stylists are now offering Ancient Sunrise® henna for hair services in their own salons. Some have ceased using oxidative dyes altogether, and work exclusively with henna and other plant dyes. Ancient Sunrise® offers free resources and training, as well as a discount to salons and stylists who use our products in their work.

Lisa Marchesi-Hunter offers Ancient Sunrise® plant dye services in her salon in Sedona, Arizona. She and her client have given permission for the use of this image.

PPD sensitization occurs at high rates in the cosmetology industry because stylists expose themselves to hair dye regularly [13]. Many develop such severe reactions that they are no longer able to work as stylists. Henna for hair offers a unique opportunity for stylists who have been sensitized to PPD to continue doing what they love without the risk of allergic reaction. By training stylists in the use of plant dyes, not only will salons be able to offer new services to maintain and build their clientele, but they will be able to employ talented individuals who might otherwise have been forced to find new work.

Stylists have a special and unique relationship with their clients. They connect at a personal level, working with both the client’s appearance and emotions. The clients see them as friends, and also trust their knowledge of hair and beauty. Studies have been done on the use of salons and barbershops as venues for discussing other health issues, such as cardiovascular disease and prostate cancer [14, 15]. It is not absurd, then, to imagine that stylists can have discussions with their clients about switching from oxidative dyes to plant-based dyes, if the client is concerned about sensitization. Now, many doctors who are familiar with the benefits of henna recommend it to their patients who have hair dye allergies. However many of these patients have a hard time finding good products and solid information, and stylists who are willing to help them apply it. It will be of great benefit for more stylists to explore and embrace natural dyes.

4. Henna for Hair Will Require Education and A Shift in Culture

The world of beauty is fast-paced, and constantly innovating. Both professionals and customers are quick to pick up on new styles, products, and techniques. Social media helps to spread new trends quickly. While only a few years ago many people would have never heard of the terms, balayage, or ombré, these are now highly sought-after styles, illustrated by thousands of images on the internet and social media sites. Special communities share and discuss techniques for a variety of hair textures and needs. The same is happening now for henna, and must continue into the mainstream, if hair dye companies wish to be successful in selling henna, indigo, and cassia plant dye powders.

This is because the process of dyeing hair with plant dye powders cannot easily fit into a small pamphlet that accompanies a product. The current model of the store-bought hair dye market sets the company as the “expert” of knowledge that is seemingly too complicated for the average customer. The company is trusted to “know what is best” for the consumer, so the consumer can simply buy a product and apply it without question. With henna, a company cannot sell a secret formula; it must provide individually packaged, pure plant powders, along with the correct resources to help the consumer learn how to use them. It is the difference between selling a can of soup, and selling the raw ingredients and a solid recipe.

Henna for hair communities encourage consumers to take knowledge into their own hands. These customers want to know what they are putting on their bodies, and exactly how to create their desired look. They want to know not only how to do it, but how it works and why it works. This new model replaces the instructional pamphlet with active learning and interpersonal interactions. Henna users use resources and each other to perfect their techniques. Passive consumption is replaced with educated consumers making active decisions based on the information they share and seek out.

Where henna was originally used, women spent entire days together at public bathhouses where they would gather to clean themselves, relax, chat, and henna their hair. These techniques were passed from person to person, and from mother to child. Now, as people bathe and groom alone, the internet takes the place as the 21st century bathhouse.

If training is made available to stylists, either through elective additional programs, or within the cosmetology curriculum, stylists can then become trusted experts and ambassadors for plant dyes. This will require that the outdated misconceptions about henna be replaced with up-to-date information. This information is already freely available through Ancient Sunrise®. We have recently designed a training program which can visit salons interested in using the brand, educating stylists on the science and technique over the course of a few days. This program is adaptable to the size and needs of each individual business. The price is dependent on instructors’ time, materials, and travel costs.

Gwyn presents to a salon company in Italy. Photo credit: Maria Moore

As the more salons begin to offer natural, safe alternatives to PPD-based hair dyes, others will follow suit in order to compete in this new market. It is very likely that, if done correctly, plant-based hair dyeing will become commonplace in the hair styling industry. One day, the use of oxidative hair dyes may be an old-fashioned, backward practice.

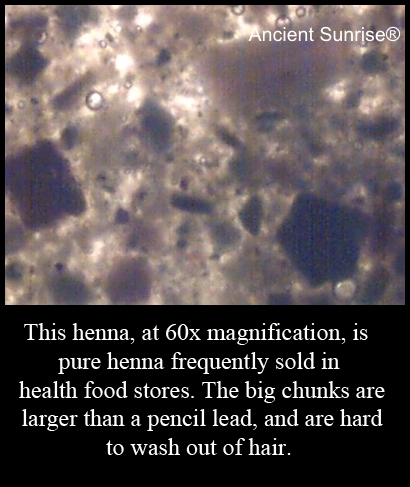

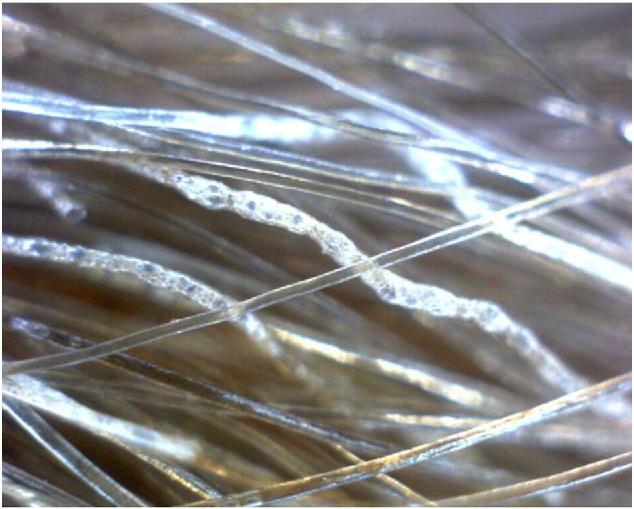

5. Mainstreaming Henna Will Require a Reliable Source of High-Quality Product

If henna is to replace PPD dyes in the western market, there will need to be enough product to meet demands. Ideally, henna for hair should be regulated to ensure quality, consistency, and safety. The product should have to meet a standard for sift quality, as well as a standard for maximum allowable pesticides, added dyes, mineral content, and other chemical adulterants (ideally, this maximum should be close to zero). Quality regulation is essential because the reputation of henna has already been tainted by decades of bad product. Stylists and consumers must trust that these products are safe, that they will not damage their hair, and that they will not interact with other products in destructive ways. Pure henna can be lightened with chemical lightening agents. It can be dyed over with oxidative dyes. Adulterated henna products cannot.

Meeting a high demand for quality product will require the existence of enough farms and milling facilities that operate within the expected standards. Henna is grown in semi-arid climates. Countries such as India, Iran, Yemen, Sudan, and Morocco have grown and produced henna. Currently, the majority of exported henna comes from the Rajasthan area of India. Political, economic, and agricultural factors have caused many countries to decrease production and cease exporting henna. A growth in demand from the western market could greatly boost the agricultural economy of those nations interested in growing and exporting henna.

Henna is a hardy, drought-tolerant crop which does not require pesticides to thrive. The life of a henna shrub is about fifty years. Because only the leaves are harvested, the crop remains in the soil year after year. The plant’s dense, twisting root system prevents soil erosion. Henna is an ideal crop to grow in the southern boundary Sahel desert in Africa, where it can add to the “green wall” project preventing desert spread. As this region has ideal conditions for henna crops, it can present a great economic opportunity for those who live and work there. Building the henna industry there will require working with locals to establish farms and mills, and maintaining quality standards.

Currently, there are no regulations on products labeled “henna” coming into the United States. Much of the henna powder currently sold for hair is poorly sifted, stale, low dye-content henna, with large plant particulates, sand, and other debris. This makes the henna difficult to apply and rinse cleanly. Hair is left tangled and with poor color results. As stated before, many products contain additional chemical adulterants.

Henna is permitted by the FDA only as a hair dye, and not for use on skin. It will be beneficial to legalize pure henna plant powder for all uses and to set up regulations based on lab testing. This way, the United States can ensure that the product entering the country is free of harmful adulterants, and that only products that meet these standards can be sold as henna. These standards should include panels for heavy metals, metallic salts, minerals, and pesticides. Additional testing can regulate sift quality. Legalization and regulation will lead to safer products and wider availability.

A henna plant and its root system.

Final Notes

PPD sensitization is rising at a rate that will soon make the current hair dye industry unsustainable. A transition from oxidative hair dyes to pure plant dyes within the mainstream market is definitely possible, but it will require earnest effort on the part of those companies which seek to make it happen.

Hair dye companies will have to completely un-learn their previous ideas of what a hair dye is, and what their consumer expects a hair dye to be. They must engage with stylists and consumers to educate them on products and techniques which are far different from what is commonly used today. They must take the time to establish farms and facilities which are capable of putting out high-quality product.

Doing so will allow for more people to dye their hair safely and with beautiful, damage-free results. It will provide alternatives for both consumers and stylists who are sensitized to PPD. It will increase opportunities for economic development in those regions suitable for growing henna, and protect those regions from desert spread. It will prevent future allergies and injuries. Switching to henna is a common-sense, feasible solution, but one that must be executed with the utmost deliberation.

References

[1] Ashraf, Waseem, Shiela Dawling, and Lew J. Farrow. “Systemic paraphenylenediamine (PPD) poisoning: a case report and review.” Human & experimental toxicology 13, no. 3 (1994): 167-170.

[2] Kligman, Albert M. “The identification of contact allergens by human assay: III. The maximization test: A procedure for screening and rating contact sensitizers.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 47, no. 5 (1966): 393-409.

[3] Mukkanna, Krishna Sumanth, Natalie M. Stone, and John R. Ingram. “Para-phenylenediamine allergy: current perspectives on diagnosis and management.” Journal of asthma and allergy 10 (2017): 9

[4] McCally, A. W., A. G. Farmer, and E. C. Loomis. “Corneal ulceration following use of Lash-Lure.” Journal of the American Medical Association 101, no. 20 (1933): 1560-1561.

[5] Brancaccio, Ronald R., Lance H. Brown, Young Tae Chang, Joshua P. Fogelman, Erick A. Mafong, and David E. Cohen. “Identification and quantification of para-phenylenediamine in a temporary black henna tattoo.” American Journal of Contact Dermatitis 13, no. 1 (2002): 15-18.

[6] Smith, Vanessa M., Sheila M. Clark, and Mark Wilkinson. “Allergic contact dermatitis in children: trends in allergens, 10 years on. A retrospective study of 500 children tested between 2005 and 2014 in one UK centre.” Contact dermatitis 74, no. 1 (2016): 37-43.

[7] McFadden, John P., Ian R. White, Peter J. Frosch, Heidi Sosted, Jenne D. Johansen, and Torkil Menne. “Allergy to hair dye.” (2007): 220-220.

[8] Wilbert, Martin I. “Cosmetics as Drugs: A Review of Some of the Reported Harmful Effects of the Ordinary Constituents of Widely Used Cosmetics.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) (1915): 3059-3066.

[9] Nohynek, Gerhard J., Rolf Fautz, Florence Benech-Kieffer, and Herve Toutain. “Toxicity and human health risk of hair dyes.” Food and Chemical Toxicology 42, no. 4 (2004): 517-543.

[10] DermNet, N. Z. “Allergy to Paraphenylenediamine.” (2005).

[11]Ahn, Hyung Jin, and Won‐Soo Lee. “An ultrastuctural study of hair fiber damage and restoration following treatment with permanent hair dye.” International journal of dermatology 41, no. 2 (2002): 88-92.

[12] Sinclair, Rodney D. “Healthy hair: what is it?.” In Journal of investigative dermatology symposium proceedings, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 2-5. Elsevier, 2007.

[13]Lind, Marie-Louise, Anders Boman, Jan Sollenberg, Stina Johnsson, Gunnel Hagelthorn, and Birgitta Meding. “Occupational dermal exposure to permanent hair dyes among hairdressers.” Annals of occupational hygiene 49, no. 6 (2005): 473-480.

[14] Releford, Bill J., Stanley K. Frencher Jr, Antronette K. Yancey, and Keith Norris. “Cardiovascular disease control through barbershops: design of a nationwide outreach program.” Journal of the National Medical Association 102, no. 4 (2010): 336.

[15] Luque, John S., Siddhartha Roy, Yelena N. Tarasenko, Levi Ross, Jarrett Johnson, and Clement K. Gwede. “Feasibility study of engaging barbershops for prostate cancer education in rural African-American communities.” Journal of Cancer Education 30, no. 4 (2015): 623-628.