Introduction

Para-phenyelenediamine (PPD) is one of the most common allergens in cosmetics. While genetics can increase chances of allergy, anyone can develop a PPD allergy. High concentrations and repeated exposure increase the likelihood of becoming sensitized. Basic information about PPD is covered in an earlier article, What You Need to Know About Para-Phenylenediamine.

Occupations that involve repeated exposure to PPD, such as hair stylists, and fur and textile workers, show higher rates of employees with PPD sensitization [13]. Outside of occupation-related sensitization, the average person is sensitized to PPD through a black henna tattoo, or through the use of hair dye. Prevalence rates of PPD sensitization are about 6.2% in North America, 4% in Europe, and 4.3% in Asia [1]. Overall, sensitization rates appear to be increasing over time [2]. Rates are higher in populations with darker hair, as dark hair dyes contain higher PPD concentrations. Rates of sensitization are also higher in countries where “black henna” is commonly used in place of traditional henna.

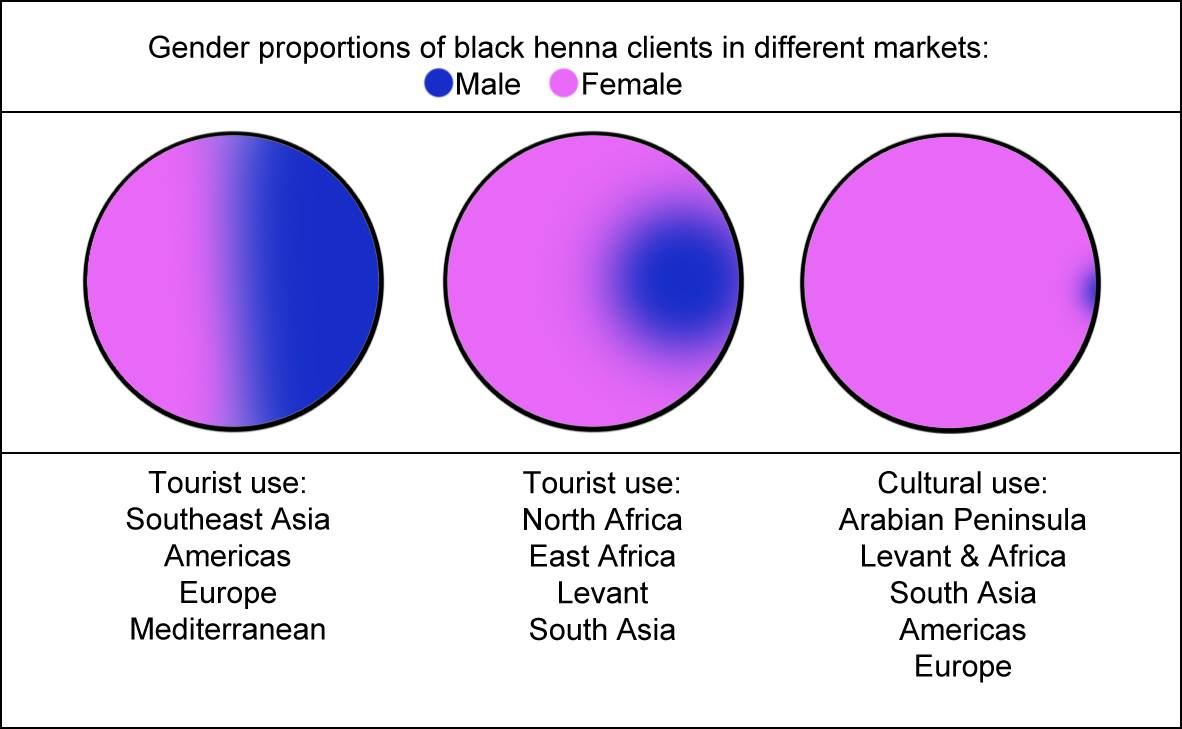

PPD sensitization rates also vary between genders. Both body art and the use of hair dye are gendered behaviors; more women participate than men. This leads some to presume that PPD sensitization is more of a concern for women. While it is true that, overall, a higher percentage of women have PPD sensitization than men, it is important to discuss issues specific to men’s self-grooming and help-seeking behaviors that put the male population at unique risks. Certain populations of men experience higher rates of facial dermatitis due to frequent beard dyeing. Men who work in industries involving frequent contact with products that contain PPD or cross-reacting allergens may be forced out of their jobs to avoid continual allergic reaction. Men show reluctance to seek medical attention; this puts them at risk for future complications which could be avoided. Understanding gendered behavior may lead to better education, prevention, and treatment of PPD sensitization in men.

Source: https://shewhoseeks.blogspot.ca/2012_02_01_archive.html

Avenues of PPD Sensitization

Traditionally, self-grooming and concerns for beauty have been characterized as feminine behaviors. Men spend less time and money in the use and consumption of beauty products and services. Gender-specific grooming practices will be explored further in the next section. About 30-40% of women and up to 10% of men in North America are regular hair dye users [2],[3]. Another study estimated that 70% of women and 20% of men have used hair dye at least once in their lifetime [4].

On the other hand, getting a “black henna” tattoo is much less gendered in western cultures, leading to a fairly even split in the numbers of males and females getting a temporary “black henna” tattoo. Traditional henna body art is highly gendered; it is used for decorating and beautifying women, especially for celebrations and social events. In contrast, “black henna,” when it is used in spaces of tourism, is used to mimic the look of true tattoos. It is not limited to a specific custom or style. “black henna” is readily available on boardwalks and beaches, and in shopping malls, resorts, amusement parks, festivals, and fairs. Those who get “black henna” body art are usually children or young adults. [5], [6]. Children are attracted to body art that mimics tattoos because they like to imitate adult behavior. Parents who believe that “black henna” is harmless allow their children to have body art done, unaware of the risk of sensitization. Thus, both young boys and girls get “black henna” body art.

Source: Daily Mail

Of those who get a “black henna” tattoo, an estimated 50% will become sensitized [6], [7]. Some will experience a delayed contact dermatitis reaction following; some will not. A person can develop a sensitization even if they did not react to their first exposure. It is rare for consumers of “black henna” to understand the connection between the product used to create “black henna” body art, and hair dye. Children become sensitized to PPD through “black henna,” then later on may choose to dye their hair. The chances of a person previously sensitized by black henna having a severe (+++) reaction to PPD hair dye is about 40% [8]. A study found that 16% of adolescents in Manchester, England had a PPD allergy. Most of this was likely caused by the “black henna” they had gotten on holiday [8]. We will see a wave of hair dye reaction cases around 2030, when this population begins showing gray hair.

While girls and women favor delicate designs, boys and men are more likely to choose tribal-style patterns that cover large areas of the skin with a solid application of “black henna.” This larger surface area increases the amount of PPD to which the person is exposed, thus increasing the risk of sensitization. If the client experiences a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the body art, a larger area of their body is subject to dermatitis symptoms such as blistering, permanent scarring, and hypopigmentation. This is only just one way gendered behavior creates unique variables in PPD sensitization.

If a parent sees that their child is suffering from a reaction to their “black henna” tattoo, they will probably take the child to a medical professional. Adults, especially men, may be less likely to seek medical attention for their own allergic reaction, especially if it is not severe. Neglecting to seek medical attention causes a person to remain uneducated about the nature of their allergy, putting them at risk for repeated exposures and reactions. Men’s help-seeking behaviors will be discussed later in this article.

Grooming Practices as Gendered Behavior

Conventional ideals for appearance differ greatly between those for men and those for women. Entire books are dedicated to the sociology behind gendered beauty norms; therefore, it is impossible to cover this subject in its entirety within this article. One salient feature is that feminine and masculine norms are often presented as binary, and in opposition with one another [9]. If one behavior is used in traditionally feminine self-grooming, it is avoided in traditionally masculine self-grooming [9], [10], [11]. This is particularly evident in the way we treat hair. In western societies, most men keep their hair short, while most women have longer hair. Of course, there are many exceptions, and there are people and groups who intentionally choose to defy norms through their appearance. As societal constructs of masculine and feminine ideals shift, so do people’s choices in personal style. However, there is still an overall trend in gendered grooming behaviors. Cosmetics companies actively seek to maintain these norms in the sorts of images they use in marketing their products.

Overall, women dye their hair more than men. Women’s fashion trends change more rapidly than men’s, and women change their personal style more frequently than men do [10], [11]. They do so by altering the length, color, and texture of their hair. Cutting, dyeing, curling, straightening, braiding, and using tools, products, and accessories all help in keeping a style “fresh” or “up-to-date.” Conventional feminine beauty values youth, and fears the appearance of age [9]. Women are much more likely to dye their hair to mask grays, while gray hair is less of a concern for most men. These behaviors play into the higher rate of PPD sensitization in women.

Men’s styles focus on conformity, consistency, and professionalism. Men do not change their hair as frequently. Feminine beauty is associated with youth; gray hair is undesirable. On the other hand, men are less concerned with going gray. Gray hair may even increase a man’s attractiveness. It is “distinguished.” The term “silver fox” is used predominately to describe mature, attractive men. Younger men in white-collar professions have even been told that adding some gray into their hair may help their appearance and rapport with clientele [9]. The brand Touch of Gray promises to dye men’s hair while leaving just enough gray to maintain that distinguished, mature image. While traditional concepts of masculinity once idealized the perfect man as rough and rugged, the increase of educated and white-collar careers caused a gradual shift to the image of a clean-cut, well-groomed, professional man, whose power comes from his professional success and wealth, and his ability to attract women [9], [10], [11].

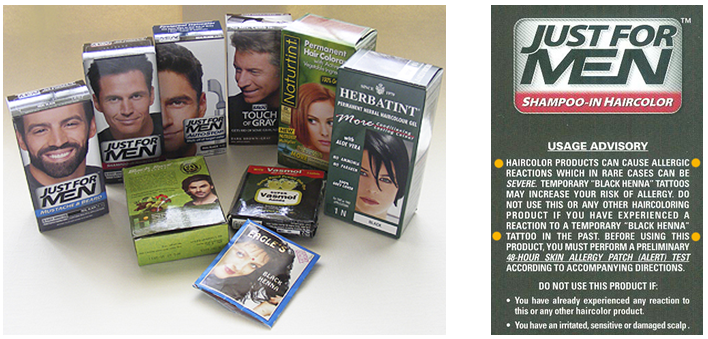

The image on the right shows the warning and patch test advisory on Just For Men dye.

Many men do dye their scalp hair and facial hair to mask their grays. The popular brand, Just for Men, directly targets men with its very name. Grooming products marketed toward men attempt to both reinforce the masculine ideal, and present self-grooming as a valid, masculine behavior. Marketing focuses on how the product will augment a man’s ability to attract women, or his image of professional success. By re-framing the use of hair and beauty products as a masculine behavior, companies can increase their number of male consumers.

Men’s use of hair dye is increasing, and the age of the average hair dye user is decreasing. More and more young people are using hair dye as a means of beauty and self expression, rather than for masking gray [22]. This shift in the demographic will lead to higher rates of sensitization and at younger ages, for both men and women.

Dyeing Beards

Facial hair is rather unique to men. Biologically, higher levels of androgen hormones lead to thicker, longer facial hair. While women also have facial hair, it is traditionally minimized through plucking, shaving, or bleaching. Few women have the biological ability to grow thick beards. Just as scalp hair can be cut, dyed, and styled to express a person’s identity, so can facial hair. Because it is mostly men who have noticeable facial hair, the use of dyes on facial hair and the repercussions are a uniquely male issue.

Facial skin is thin and sensitive. Facial hair, on the other hand, is coarser and more resistant to dye [12]. Those who dye their beards might choose stronger, more concentrated products, or leave the dye on for longer periods of time. This increases the chances of becoming sensitized to PPD. Additionally, a person who dyes their facial hair most likely also dyes their scalp hair, and possibly dyes both at the same time for the sake of convenience. Those who are already sensitized may experienced more severe reactions when the compound comes in contact with their face. The proximity to the nose and mouth leads to further risks.

Because facial hair grows quickly, a person wishing to mask gray roots will have to dye frequently. Men who use beard dye do so as frequently as once every five days [12], [13]. Men who keep their scalp hair short will also show gray roots more quickly. Repeated exposures both increase the chances of becoming sensitized to PPD, and worsen symptoms for those who are already sensitized.

Furthermore, PPD sensitization can lead to cross-reactions with several structurally similar compounds, including those found in synthetic fragrances. If a man later chooses to shave their facial hair, the process of doing so can create cuts and micro-abrasions that leave the skin vulnerable to reactions from soaps, lotions, and aftershaves [14].

Ethnicity, Culture, and Class in PPD Allergy Variability

A population’s variation in PPD allergy prevalence rates is dependent on several factors, such as behavior, the accessibility of PPD products, and the concentrations within those products. Demographics and geography play into these factors. In many European countries, laws have limited the maximum concentration of PPD allowed in hair dyes, and a related compound, para-toluenediamine (PTD) is often used instead [2]. (Side note: PTD is believed to be less sensitizing than PPD, but those who are already sensitized to PPD are likely to experience a cross-reaction with PTD. We’ll save that can of worms for another time.) In countries where PPD concentration in hair dye is restricted, or where PTD is more commonly used, sensitization rates to PPD are lower [4]. The same goes for countries with greater light-haired populations [1].

Conversely, in countries with less restriction on PPD concentration, and with larger dark-haired populations, we see higher sensitization rates. In many Asian countries, hair dyes with high PPD concentrations are easily available. Popular hair dye brands can contain up to 80% PPD. “Henna stone,” which is solid industrial PPD, is widely sold for use in hair dye and body art [6], [7]. The median prevalence rate in Asia is 4.3%, but ranges from 2-12% within regions and sub-groups [13].

In Saudi Arabia, and among Arabic men regardless of their location, growing and coloring beards is common practice. The prevalence rate for facial dermatitis from dye is high among this population [12]. A Korean study found that about 64% of adults with gray hair had experience using hair dye, and of that group, about 24% experienced a reaction [15].

A study conducted by the Cleveland Clinic investigated sensitization rates in white and black racial groups, and found that rates were similar among both groups for all allergens except PPD. Black people overall showed much higher rates of PPD sensitization than white people (10.6% vs. 4.5% respectively), and black men had much higher sensitization rates than black women (21.2% vs. 4.2% respectively) [16]. This is likely influenced by a combination of hair dye use/exposure, occupation, and genetic differences.

Black hair care is nearly a multi-billion dollar industry. Black women spend more money on cosmetics than non-black women. However, this alone does not explain why black men have significantly higher sensitization rates than black women. One factor could be that black men who dye their beards must do so frequently, and with high PPD concentrations, similar to the phenomenon seen in Arabic men. One class-action lawsuit against the Just For Men hair and beard dye brand claims that JFM unfairly targeted African American men in their marketing of a product that contained higher levels of PPD.

Additionally, there may be a higher proportion of black men (in comparison to non-black men, and black women) in industries which handle PPD and related compounds, such as fur/leather/textile dyeing, and the manufacture and handling of black rubber products in rubber and automotive industries.

One can look at a statistic for PPD sensitization in, say, North America for example, and make an assumption that all of the population is at equal risk. This is far from the truth; sensitization rates vary greatly between sub-groups. More research needs to be done on specific populations to determine these sub-groups, and the factors which lead to higher rates of sensitization. Hair dye and “black henna” use, as well as occupation cause significant variation. More nuanced demographic data will create a clearer picture of the populations that might require additional attention.

Help-Seeking Behavior, Education, and Prevention

Sociological studies in men’s help-seeking behavior affirm that men are less likely than women to use medical services. Studies have focused on mental help and addiction, as well as common physical ailments such as headache and backache [17], [18]. There has yet been a study specifically regarding the help-seeking behaviors of men and women who experience a reaction to “black henna” tattoos, or PPD hair dye. However, one can infer from the general trend of help-seeking reluctance that there is a large population of men who are sensitized to PPD, who are entirely unaware of the allergy or how to manage it.

Overall, most people who become sensitized to PPD from a “black henna” tattoo are not aware that the sensitizing agent, PPD, is the same compound used in hair dye. Numerous case reports have described patients seeking medical care for reactions to hair dye, who reported having gotten a “black henna” tattoo in the past [1-8], [13], [19-22]. It is estimated that, of those who experience a severe reaction to hair dye, only 10-30% of cases will be seen by a doctor, and even fewer by a dermatologist. [19], [20]. In a survey of 521 Korean adults with graying hair, a whopping 74% of those who reported experiencing a reaction to hair dye said that they did not visit a medical professional. The primary reasons were that they did not feel the reaction was severe enough (44.6%), and that they saw the side effects as a normal part of dyeing their hair (39.3%) [15]. Another article estimated that only 15% of people with a hair dye allergy seek treatment, and only a fraction of these people are patch-tested for allergies [22].

Societal influences cause men in particular to choose to “tough out” medical problems rather than seeking help. If a man experiences a reaction to PPD and chooses not to seek medical help, he deprives himself of crucial information related to his sensitization. Most likely, he will think it was a one-time fluke. He might not learn that “black henna” and conventional hair dyes both contain PPD. He might not learn that PPD sensitization can lead to cross-reactions with other products such as black rubber, fabric dyes, photographic developer and lithography plates, photocopying and printing inks, oils, greases and gasoline.

Without consulting a dermatologist or allergist, someone who is sensitized may never learn how to properly manage their new allergy, putting them at risk for repeated exposure and worsening symptoms. Furthermore, PPD sensitization can limit prospective occupations, or force workers to leave their jobs due to continuing and worsening reactions to the materials involved. This would affect people in cosmetology, fur and textile industries, rubber industries, automotive industries, work that involves printing and photo development, and numerous other fields [2].

Studies suggest that men’s help-seeking choices are influenced by the perceived potential for embarrassment, as well as the perceived normality of a problem. If an issue is ego-centric, meaning that it may affect a person’s self-image, men are less likely to seek help. The same goes for if a man perceives a problem as abnormal [17]. Advertisements for erectile dysfunction medications have focused on normalizing ED, as well as reinforcing the notion that the embarrassment of ED is worse than the embarrassment of consulting a doctor. This is an example of an attempt to normalize a medical issue and decrease the help-seeking behavior’s threat to a man’s self-esteem.

While statistics show that few people seek medical treatment for reactions to hair dye, additional factors may cause men to do so even less. First, men are less likely to seek medical help than women. Second, because traditional masculine ideals enforce the belief that preoccupation with beauty, especially hair, is a feminine behavior, many men may be hesitant to seek help for reactions to hair dye. Doing so requires admitting to the use of hair dye, which can create a blow to a masculine self-image. While PPD is one of the most common allergens (named Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society in 2006), people remain largely unaware of its risks. Women are more familiar with hair dye reactions than men. Men may perceive a reaction to hair dye to be both non-normal and a threat to self-image. Thus, it is essential that efforts be made to increase awareness about PPD sensitization, focusing on its severity, high likelihood, and prevalence.

Just for Men Class-Action Suit

The hair dye brand, Just For Men, is currently at the center of several class-action lawsuits. Users reported experiencing adverse reactions to the products on their scalp hair and/or facial hair. Some suits claim that the patch test advised in the packaging was not sufficient for determining how the product would affect the skin on the scalp and face. In fact, conducting a patch test may increase sensitization. As mentioned earlier, other suits claim that the company intentionally and unfairly targeted black men in their marketing of their Jet Black hair dye, which the legal group claims to contain 17 times more PPD than other dyes from the same company.

If you are a man who has experienced an allergic reaction to Just for Men, consider looking to find if there is a legal group with an open suit in your area.

This series of class action suits is a positive move forward in demanding stricter regulation and more responsibility on the part of hair dye companies. Such legal action has rarely occurred against companies marketing hair dye to women, and fewer acts have been successful. Overwhelmingly, users of hair dye see adverse effects as a “normal” part of the hair dyeing process, and even choose to continue using products that cause reactions because the thought of going gray is worse than enduring contact dermatitis symptoms [15].

Conclusion

Because women make up the majority of hair dye users, there is a paucity of research specific to men’s use of hair dye. It is likely that more men are sensitized to PPD than current numbers suggest. Data taken from medical databases and case reports only include those people who seek medical attention or make themselves available to researchers. Surveys depend on honest self-reporting of behaviors. Men’s help-seeking behaviors may have cause research numbers to be lower than the reality

Based on available data, men make up a smaller proportion of the PPD sensitized population, in comparison to women. There is an exception in the case of black men in the United States. While hair dye allergies are often framed in the context of the female consumer, it is critical that the male population not be forgotten. The use of dye on beards is unique to men and poses special risks. Studies on help-seeking behavior suggest that men are less likely to seek medical attention if they were to experience a reaction. The idea of self-grooming as a gendered behavior further prevents men from openly discussing their use of hair dye.

Young boys who get a “black henna” tattoo on vacation, while at an amusement park, or in other tourist settings, are at risk of experiencing a reaction later on in life if they choose to use oxidative dyes. “Black henna” tattoos contribute significantly to the number of people who have PPD sensitization. In the future, we will see an increase of both men and women who develop severe reactions to hair dye. As societal ideals of beauty, self-grooming, and gender norms change, hair dye use may increase among men. Already there is a shift in the use of hair dye as tool for masking age, to an avenue of self-expression in younger populations [22].

In order to ensure that both men and women are properly educated about the risks and prevalence of PPD sensitization, continued efforts must be made in raising awareness. Consumers should be aware that PPD is highly sensitizing, and that reactions from hair dye are quite common. Steps must be taken to prevent PPD sensitization before the onset. This includes continuing to raise awareness about “black henna” body art, pushing for stricter regulation of products containing PPD, and presenting safe alternatives for altering hair color and masking grays.

To learn more about PPD sensitization, visit the following links.

The Henna Page: Black Henna Warnings

Catherine Cartwright-Jones’ PhD Dissertation, “The Geographies of the Black Henna Meme Organism and the Epidemic of Para-phenylenediamine Sensitization: A Qualitative History”

AncientSunrise.Blog: What You Need to Know About Para-Phenylenediamine

To learn how to use plant dyes as a safe and effective alternative for coloring hair and masking grays, read the Ancient Sunrise® Henna for Hair E-Book and visit www.HennaforHair.com, and www.Mehandi.com.

References

[1] Mukkanna, Krishna Sumanth, Natalie M. Stone, and John R. Ingram. “Para-phenylenediamine allergy: current perspectives on diagnosis and management.” Journal of asthma and allergy 10 (2017): 9.

[2] Hamann, Dathan, Carsten R. Hamann, Jacob P. Thyssen, and Carola Lidén. “p‐Phenylenediamine and other allergens in hair dye products in the United States: a consumer exposure study.” Contact Dermatitis 70, no. 4 (2014): 213-218.

[3] Redlick, Fara, and Joel DeKoven. “Allergic contact dermatitis to paraphenylendiamine in hair dye after sensitization from black henna tattoos: a report of 6 cases.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 176, no. 4 (2007): 445-446.

[4] Schuttelaar, Marie-Louise Anna, and Tatiana Alexandra Vogel. “Contact Allergy to Hair Dyes.” Cosmetics 3, no. 3 (2016): 21.

[5] Goldenberg, Alina, and Sharon E. Jacob. “Is the Use of PPD in Black Henna Tattoo Criminal or Remiss?.” International Journal of Integrative Pediatrics and Environmental Medicine 1 (2014): 22-26.

[6] ‘Black Henna’ and the Epidemic of para-Phenylenediamine Sensitization: Mapping the Potential for Extreme Sensitization to Oxidative Hair Dye, Presentation at Society of Cosmetic Chemists’ 70th Annual Scientific Meeting, December 10, 2015, Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[7] Presentation to USFDA June 30, 2016: ‘‘Black Henna’ and the Epidemic of para-Phenylenediamine Sensitization: Awareness, Education and Policy, Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[8] Smith V, Clark S, and Wilkinson M. “Allergic contact dermatitis in children: trends in allergens, 10 years on. A retrospective study of 500 children tested between 2005 and 2014 in one U.K. centre.” British Association of Dermatologists’ Annual Conference. Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, U.K. (2015).

[9] Synnott, Anthony. “Shame and glory: A sociology of hair.” The British journal of sociology 38, no. 3 (1987): 381-413.

[10] Ricciardelli, Rosemary. “Masculinity, consumerism, and appearance: a look at men’s hair.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie 48, no. 2 (2011): 181-201.

[11] Barber, Kristen. “The well-coiffed man: Class, race, and heterosexual masculinity in the hair salon.” Gender & Society 22, no. 4 (2008): 455-476.

[12] Hsu, Te-Shao, Mark DP Davis, Rokea el-Azhary, John F. Corbett, and Lawrence E. Gibson. “Beard dermatitis due to para-phenylenediamine use in Arabic men.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 44, no. 5 (2001): 867-869.

[13] Handa, Sanjeev, Rahul Mahajan, and Dipankar De. “Contact dermatitis to hair dye: an update.” Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology 78, no. 5 (2012): 583.

[14] Jensen, Peter, Torkil Menné, Jeanne D. Johansen, and Jacob P. Thyssen. “Facial allergic contact dermatitis caused by fragrance ingredients released by an electric shaver.” Contact dermatitis 67, no. 6 (2012): 380-381.

[15] Kim, Jung Eun, Hee Dam Jung, and Hoon Kang. “A survey of the awareness, knowledge and behavior of hair dye use in a Korean population with gray hair.” Annals of dermatology 24, no. 3 (2012): 274-279.

[16] Dickel, Heinrich, James S. Taylor, Phyllis Evey, and Hans F. Merk. “Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups.” American Journal of Contact Dermatitis 12, no. 2 (2001): 77-82.

[17] Addis, Michael E., and James R. Mahalik. “Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking.” American psychologist 58, no. 1 (2003): 5.

[18] Hunt, Kate, Joy Adamson, Catherine Hewitt, and Irwin Nazareth. “Do women consult more than men? A review of gender and consultation for back pain and headache.” Journal of health services research & policy 16, no. 2 (2011): 108-117.

[19] Søsted, H., T. Agner, Klaus Ejner Andersen, and T. Menné. “55 cases of allergic reactions to hair dye: a descriptive, consumer complaint‐based study.” Contact dermatitis 47, no. 5 (2002): 299-303.

[20] de Groot, Anton C. “Side‐effects of henna and semi‐permanent ‘black henna’tattoos: a full review.” Contact dermatitis 69, no. 1 (2013): 1-25.

[21] Jacob, Sharon E., and Alina Goldenberg. “Allergic.”

[22] McFadden, John P., Ian R. White, Peter J. Frosch, Heidi Sosted, Jenne D. Johansen, and Torkil Menne. “Allergy to hair dye.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 334, no. 7587 (2007): 220.