Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Sample Selection And Label Analysis

- Powder and Paste Qualities

- Chromatography

- Set 1: Dye Released Paste Samples

- Set 2: Powder and Water Samples

- Discussion

- Limitations and Considerations

Introduction

There is a wide variety of products available for coloring hair which claim to be pure henna, or which claim to contain pure henna powder along with additional natural plant ingredients. There is no international standard for what can be marketed as henna, and it is often difficult to tell which products are what they claim to be. Many henna for hair products lack an ingredient declaration. A package may show only some ingredients or have no ingredients list at all.

Additionally, products which claim to contain all-natural ingredients vary in quality as there are no internationally agreed upon standards for “all natural”. Powders may be poorly sifted, containing sand or larger plant particles which make for difficult application and removal. Stale or low dye-content henna products may contain additives such as additional dyes or metallic salts to compensate for poor quality of materials. Green dye may be added to henna powder to make it look fresher.

The FDA has a standard for henna and products entering the United States labeled as a “henna” hair coloring product. These guidelines are do not appear to be regularly enforced as are regulations for products labeled as henna for use on skin.

The FDA forbids the sale of and is empowered to confiscate of any henna product labeled for skin use, or products showing images of henna used on skin. Customs and border protection is empowered to search the importing company’s website to determine if henna is intended for use on skin, and may seize and destroy henna that appears to be imported for use on skin.

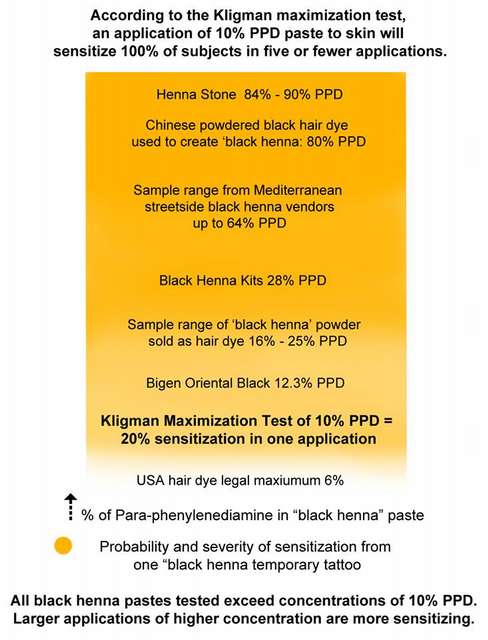

“Black henna,” or products labeled as henna containing PPD, have been known to cause skin reactions and sensitization. For more information about black henna, read the articles “Henna is not Black,” “What You Need to Know About PPD,” and Chapter One of the Ancient Sunrise E-book.

This article is the first of a series that will test and compare various “henna for hair” products which have been found online on sites such as Amazon and Ebay, in import stores in the USA, and in ‘health food stores’. The purpose of these studies will be to determine the quality of those products in comparison to Ancient Sunrise® Henna for Hair products, and to test for the existence of dye additives. This series will feature articles investigating products within the following categories:

- 1.“Pure” henna, herbal henna mixes, and red result henna for hair products

- 2. Brunette result henna for hair products

- 3. Black result henna for hair products

This article will cover the first category by investigating nine samples of retail henna hair dye products which are labeled and/or advertised as 100% pure henna, a 100% natural mix of henna and additional “herbs”, or as henna-based hair products which claim to color the hair red. Subsequent articles will report on henna for hair products claiming to color hair brunette and black.

The first part of this article will report on product labeling, visual and textural qualities of the products as dry powders, and visual and textural qualities of products when mixed with liquid to form a paste. The second part of this article will report the results of paper chromatography tests designed to determine the existence of dyes, lawsone or otherwise, in each sample.

Sample Selection and Label Analysis

Nine “henna” hair dye products were selected based on the following criteria:

1) The product claims to contain only 100% natural henna.

OR

2) The product claims to be 100% natural, containing henna along with additional “herbs.”

AND

3) The product either claims a red result or does NOT claim to dye the hair brunette or black.*

*Products that claim to contain henna and other plant powders for brunette and black hair results will be tested and reported in future articles.

Not all products that are marketed as 100% pure henna state explicitly state a hair color result, as some are marketed for both hair and skin, as well as for mixing with other plant dye powders such as indigo. Henna has been used for hair, skin, and home remedies for centuries. It can be assumed that if a product claims to be 100% henna, it should provide a reddish result on lighter hair..

These products are a random collection of henna products purchased in shops and online, easily accessible to the retail consumer. In fact, very few brands, if any, submit their plant dye powders to the same testing standards as Ancient Sunrise®. Ancient Sunrise® products are sent to an independent laboratory for multiple tests prior to sale to ensure they do not contain adulterants, accidental or deliberate.

Below are images of the labels for the nine samples. Beyond this section, each sample will be referred to as its corresponding number. They will be tested alongside Ancient Sunrise® Rajasthani Twilight henna powder, which will be referred to as “AS”.

Sample #1

The product claims to be 100% natural. The ingredients are reported as “100% Natural Henna Powder.” The product also claims to be organic.

This product fits into criterion 1. There is no information suggesting there are other ingredients other than henna. The label would lead the everyday consumer to assume that the contents of the packaging are pure, natural henna powder.

However, descriptions on sites selling this product claim a “Beautiful golden brown color” which is inconsistent with results expected from pure henna. This would suggest either 1) The product is not what it claims to be or 2) Poor quality product and/or poor instructions lead to a lighter result.

Instructions are included on the back of the packaging. On the side of the box, it states that this is a product of India.

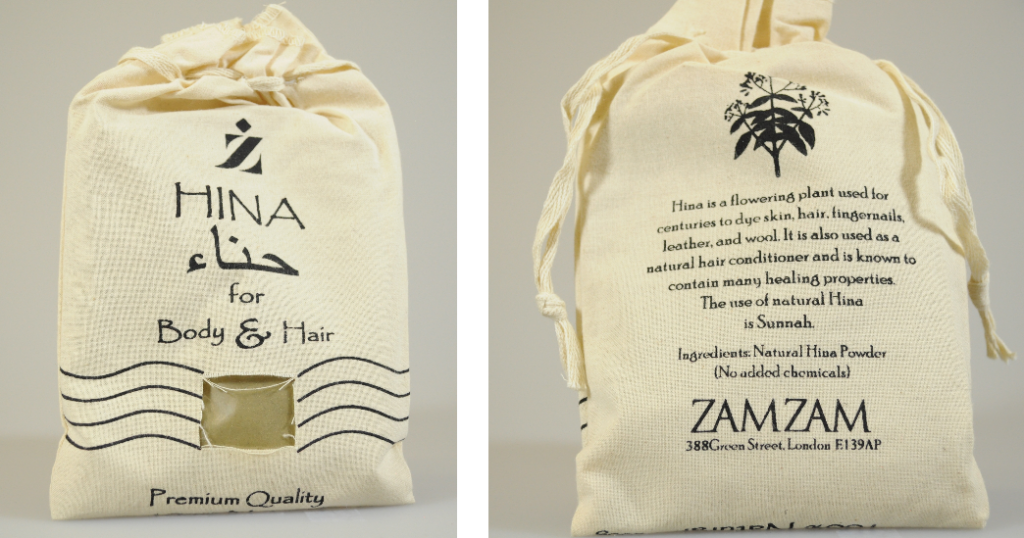

Sample #2

This product fits both criteria 1 and 3, as it claims to be 100% natural henna powder, and also reports a red result in addition to showing multiple images of red hair on the packaging.

No instructions were provided. The label includes an address of an import company. The website listed does not exist. Some additional searching found that the company has a contract with a manufacturing and export company in Pakistan, and that this is one type of product they export, along with clothing and gift items.

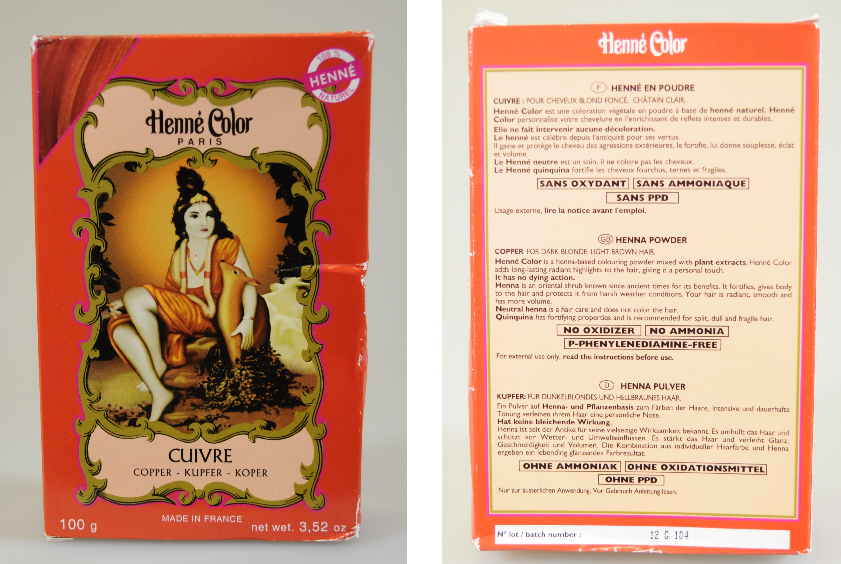

Sample #3

While the front of this package claims it is 100% natural henna, and states that the shade is copper, the back is unclear. It says “Copper: for dark blond, light brown hair,” which most likely means that dark blonde or light brown hair may be colored to a copper color. It also mentions “neutral henna” which suggests that it contains cassia obovata. However, on the website, the only ingredient listed for this product is “Lawsonia inermis (henna) leaf extract.” Based on the reported ingredients, this product fits criterion 1 as a product that claims to be pure henna.

A pamphlet included in the box provides instructions which recommend mixing the paste with hot water and applying once the mixture has cooled.

While the packaging says that the product is made in France, there is no indication of the origin of the henna powder. If it does contain henna, it is most likely mixed and/or assembled in France with ingredients imported from elsewhere.

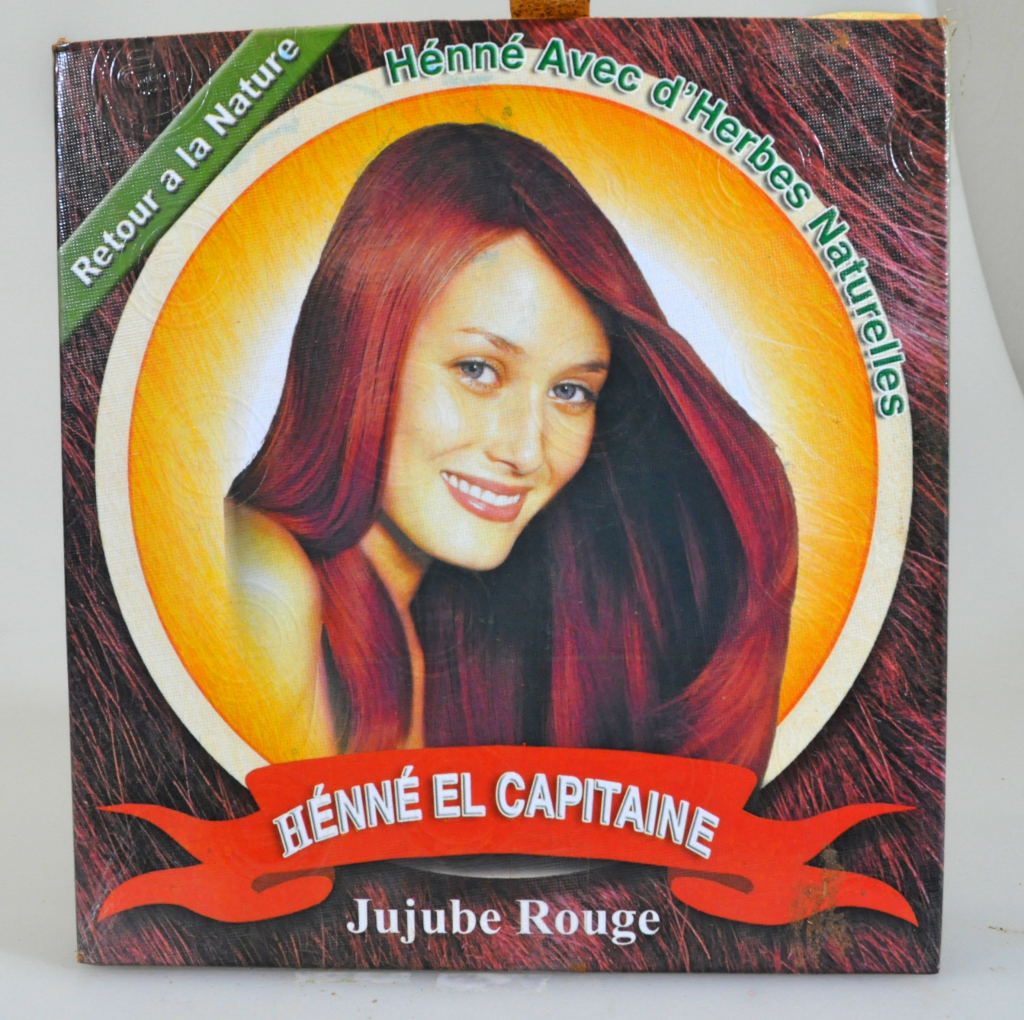

Sample #4

This product claims to contain henna under the insert’s first section, “Composition.” It claims to provide a deep red result. However, the description is confusing, as it states that lawsone and “mannitte” are responsible for coloring. If mannite is to be understood as the sugar alcohol, mannitol, it would not affect color.

The product claims to be “Henna with natural herbs,” but these additional ingredients are not reported anywhere. In the chromatography section, it will become clear that this product clearly contains more than just henna powder.

This product includes instructions on the insert, and is a product of Egypt.

Sample #5

This product’s label includes something close to an ingredients list, as it reports henna powder along with additional herbs which are meant to affect the color result as well as to condition the hair.

This product fits criterion 2. There is no indication of color result, other than stating that the blend of herbs and henna “give the dark color”. In fact, the label states “It does not contain any colour or dye.” This may be intended to mean that the product does not contain any synthetic dyes. If the product does contain henna, it would color light hair a red tone. None of the additional herbs listed are ones which produce a dye, but some plant powders can affect the tone of hennaed hair. This is most likely what the packaging means to suggest.

The instructions recommend mixing the product with water in an “iron vessel”* and letting it sit for to hours. If the product does contain amla powder, it may be enough to create an acidic mix.

The product was manufactured in India.

*An iron dye pot can be effective at decreasing the vibrancy of dye colors in a boiling pot to dye yarn or cloth, but will not change the result of henna on hair. The iron pot may cause the dye released paste surface to look browner, but there is no significant effect on the hair.

Sample #6

This product, like #5, is labeled as a henna and herbal mix for conditioning hair, but does not explicitly state a color result. On the product’s site, it is described as providing a “rich burgundy shade.”

The front of the packaging includes the words “100% natural” and “Mehendi,” another term for henna. It is unclear whether this should be read as two phrases or one, as the from also clearly states that there are nine additional herbs. The back of the package describes supposed benefits of the added herbs. The phrase “Rajasthani Mehendi” means that the henna in this product is from the Rajasthan region of India, which is where much of the world’s henna, including Ancient Sunrise® henna, is grown.

The ingredients list states that henna powder is the first ingredient, followed by powder forms of the following: aloe, neem, brahmi, bhringraj, amla, hibiscus flower, shikakai, jatamansi, and methi. All of these ingredients are commonly known and sold in South Asian stores as health and beauty herbs.

This product has instructions on the back of the packaging. It recommends mixing the powder with water and letting it sit for 2-3 hours. Like sample #5, it is possible that some of the added herbs are acidic enough that water would be enough. It also suggests adding oil or curd for “extra softness.” Doing so would affect the dye uptake, leading to lighter results. To learn more about what not to add to henna mixes, read Henna for Hair 101: Don’t Put Food On Your Head.

It is from India, and is a very popular “henna for hair” product both in South Asia and in the States, and is widely available online and in international grocery stores.

Sample #7

This product claims to contain henna. The brand’s website describes it as a 100% natural product. The site also sells “henna neutral” (cassia powder) and “henna black/basma” (indigo powder), which would suggest that their “henna red” is their henna (lawsonia inermis) powder. Therefore, this product seems to fit criterion 1, a product is labeled/advertised as a 100% pure henna powder product, but it is not entirely clear due to a lack of ingredient declaration.

However, the table on the back seems inconsistent with true henna results, as they suggest that, one would see some variation of brunette or copper results. Like sample #1, it is possible that this is either due to the product containing additional ingredients, or ineffective mixing/application methods.

I will still include this product in within this group of samples because it is both labeled as henna, includes the word “red,” and the website claims it is a 100% natural product.

There is a US address on the back, but no indication of where the henna was grown.

Sample #8

This product fits criterion 1 as it claims to be 100% natural henna. It includes instructions on the back of the packaging. The brand’s website appears to sell additional hair care products such as shampoos, conditioners, and oils. The product has an Indian address on its packaging.

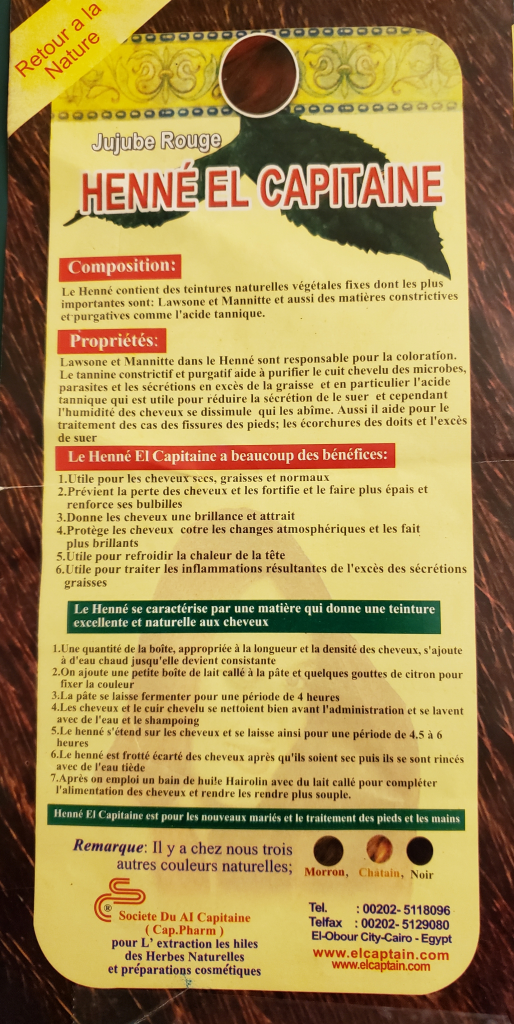

Sample #9

This product qualifies for criterion 1 as a product that claims to be pure henna powder. The information made available on this packaging is minimal. It states that it contains natural “hina” (henna) powder with no added chemicals, and that henna has been used as a dye for centuries. There are no instructions. The address listed is in London, UK, but the source of the henna is not listed. An internet search found that this brand, like sample #2, is part of an international exporting company that sells a variety of items such as health product, gifts, and books. It specializes in Islamic items.

Powder and Paste Qualities

There was a wide variation in powder sift, texture, and scent among the samples. When mixed with liquid, the resulting pastes also varied in qualities.

Ancient Sunrise® henna is grown in the Rajasthan region of India and is finely sifted. Many of the Rajasthani hennas have a slimy, stringy texture when made into a paste. This is because henna plants will have more or less natural mucilage depending on the cultivar (variety of plant). Not all hennas have this texture, and some are naturally more creamy. Pakistani henna tends to have less mucilage and a greater coefficient of expansion. The higher coeffient of expansion and lower mucilage leads to paste cracking when henna is used as body art; it does not make any difference in hair application.

It could be assumed that hennas manufactured in a country were also grown there, unless the address is outside of where henna is naturally grown, such as those products with company addresses in Europe or the United States. In the case of the latter, it not possible to determine the origin of the henna. More information on this textural quality of henna pastes can be found on page 23 and 24 of Chapter Four: Henna Science and Microscopy from the Ancient Sunrise free E-book.

Quality henna powder should not be gritty, chunky, or contain visible pieces of plant leaf and/or stem. Henna should not bubble or turn frothy when mixed with liquid. Some other plant powders which contain saponins, such as Zizyphus, do froth. Bubbles may also indicate some reaction between the acidic liquid and an unknown ingredient in the powder.

Pure henna has a neutral, plant-like odor similar to dried straw or hay. It does not smell floral or spicy; it smells like leaves. Pure henna powder does not have a perfumed, pine, camphor, or eucalyptus scent. Henna powders can vary in color from light green to olive green. While color can be indicative of the powder’s freshness and quality, it is not always the case. Powders can be made greener by adding dyes.

For products labeled as henna for use on hair, the FDA has the following specifications:

“It shall not contain more than 10 percent of plant material from Lawsonia alba Lam. (Lawsonia inermis L.) other than the leaf and petiole, and shall be free from admixture with material from any other species of plant.

Moisture, not more than 10 percent.

Total ash, not more than 15 percent.

Acid-insoluble ash, not more than 5 percent.

Lead (as Pb), not more than 20 parts per million.

Arsenic (as As), not more than 3 parts per million.”

In other words, a product labeled as henna needs to be made from the leaf or petiole (leaf stalk) of the plant rather than the bark, roots, or any other part. It should be a dry good. It should contain no more than 15 percent inorganic filler, or ash. This can include substances such as sand and metallic salts. “Free from admixture with material from any other species of plant” means that products containing henna mixed with other herbs or plant materials are illegal to enter the United States. Several of the products selected for this article are labeled as herb mixes. Others, while labeled as pure henna, smell like additional herbs were included but not reported on the labeling or ingredients.

Please note that even if a henna product conforms to FDA standards, this does not necessarily make it a quality product. This list is simply the minimum for what the FDA considers an acceptably safe product for sale and use within the United States. A product labeled as henna for hair could be roughly ground henna leaves with 15% sand and still be legal. It is also important to mention that this article does not aim to determine the legality or safety of any of the products tested. This article serves only to report on observable physical qualities and on the presence of dyes in each product.

Below are the observations on each sample.

#1. This product was labeled as 100% natural, organic henna powder. No other ingredients were reported. The color was not of any concern. However, there was a faint herbal scent that suggested additional plant powders were added, most likely one or more of those commonly found in henna herbal mixes, such as shikakai, neem and so forth. The sift was fine. When mixed into a paste, the consistency was acceptable; its a slimy, gel-like texture was similar to Rajasthani hennas, such as the AS sample. This makes sense, given that product was from India.

#2. This product also claimed to be pure henna. However, there was a very noticeable herbal scent. The color of the powder was much deeper than a henna powder should be, almost like the color of nutmeg powder. Larger particles in the powder suggested a low sift. When mixed into a paste, the product frothed slightly and had a gritty consistency. The paste also showed a darker color than would be normal for a henna paste that had just been mixed. Shikakai powder has a red tone and herbal scent, lathers slightly when mixed. This may explain the qualities in found with this product, but would mean that the product is definitely not pure henna.

#3 The product claimed to be pure henna. There was nothing out of the ordinary about the color or texture of this product. Some of the powder formed soft lumps which could be broken with light pressure. There was no discernible scent beyond a normal plant-like scent. The color was acceptable for henna powder. The paste consistency was thinner and runnier than the others, despite all powders being mixed with the same amount of liquid.

#4. The product was labeled as “henna with natural herbs.” There was a very strong herbal scent of something other than henna. The powder was a vivid, brick red, and did smell like the other “herbal hennas” and like samples #1 and #2. The powder had large plant particulate matter and long, thin pieces of plant fiber. When liquid was added, the liquid itself immediately turned blood red even prior to mixing. The paste, after mixing, was blood red. This suggests that the product contains a water-soluble red dye. The paste texture was much grittier than a normal henna paste should be. Shikakai would not be a sufficient explanation for the color of this powder because while it has a red color, shikakai does not produce a dye.

#5. This product was labeled as henna with added herbs. The scent matched this. The powder showed large stem and/or leaf fiber particles which were easily visible to the naked eye. The paste consistency reflected this lower level of sift. There was a slight sliminess to the paste; if better sifted, the product may have produced a paste similar to a Rajasthani henna. The light green-brown color of the powder and paste was similar to how a henna product should appear.

#6. This product, like #5, was labeled as an herbal henna. Both had similar added herbs reported on their packaging. The product was better sifted than #5, but some plant particulates were visible. The powder had an herbal scent. The paste showed more of the shiny, slimy mucilage texture than #5, but not as much as can be seen in the AS sample. This would match the packaging’s statement that the henna was from the Rajasthan region of India. The powder and paste colors were a light green-brown consistent with natural henna products.

#7. This product was the “red henna” product of three sold by the company: Red (henna), Neutral (cassia), and Black (indigo). One might assume that the products are sold for the purpose of mixing, much like Ancient Sunrise plant dye powders, but it is not clear. The powder was of a light green color with pieces of plant fiber visible. The powder had an odor consistent with henna, but the product frothed when mixed with liquid. The paste was quite gritty.

#8. This product was labeled as 100% natural henna. The color was of a light greenish straw tone, along the lines of a standard henna powder color. In color, it was the sample most similar to the AS sample. When mixed with liquid, the resulting paste was noticeable gritty, but with some mucilage. There was no herbal scent.

#9. The product was also labeled as 100% natural henna. The color of the powder was deeper than what might be accepted from a henna powder, almost a muddy green. The powder appeared fairly well sifted, with some very thin, long plant fibers visible. The paste was fairly smooth but not slimy, and a mid-brown color. There was no herbal odor.

AS. This powder is finely sifted, soft to the touch, and a pale green color. No large leaf or stem pieces or fibers as visible. There is a faint dried-hay scent. The paste was a clay-green color had a smooth, slimy texture. In fact, in comparison the other samples, this sample took more focus to apply the paste to paper chromatography strips because of its mucous-like texture.

Chromatography

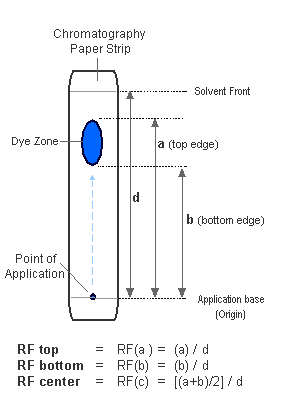

Paper chromatography is a simple method used to separate dyes in order to determine the presence of one or more dyes. The method involves placing a small sample of a substance onto a thin strip of absorbent paper, then hanging the strip so the end of it is just below the surface of a liquid solvent.

As the solvent travels up the strip, dyes move along with it. Dyes which differ in chemical structure will move at different rates before stopping. The result is that each individual dye will create its own mark at a certain place between the point of application and the solvent front (the highest point that the solvent reaches). Multiple dyes will show as multiple marks.

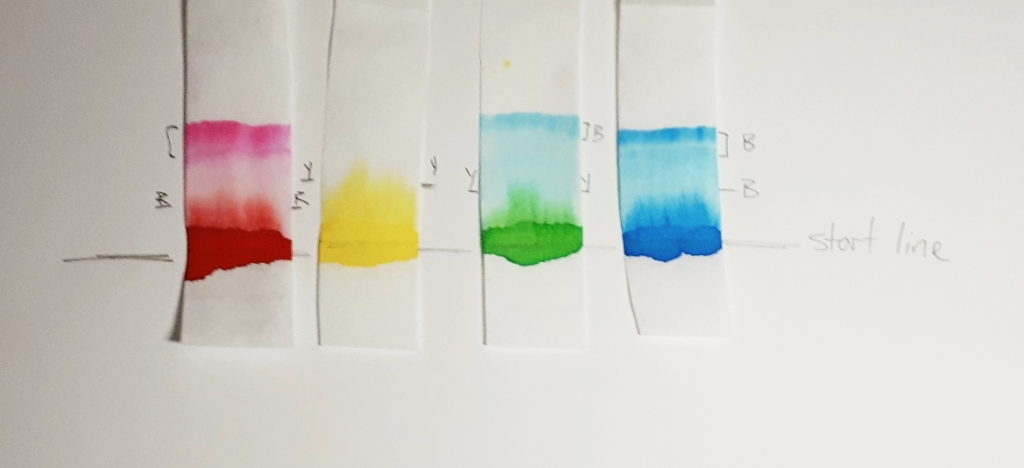

Below is the result of a paper chromatography test done on store-bought food coloring. One can see that the green dye is a combination of yellow and blue dyes, which were separated through the chromatography process.

One drawback of the simpler paper chromatography method is that it alone cannot identify the dye in each sample unless the target dye is already known. Because Ancient Sunrise henna powders are tested by an independent lab, it can be assumed that the only dye present is lawsone, which will show a dye band distinct from other dyes’ banding. If a product results in one or more bands that appear different from lawsone, it can be assumed that other dyes are present.

It was necessary to test each product under multiple conditions to achieve as full a picture as possible. Because the target dyes involved were unknown, it was not possible to test for specific dyes. Instead, each sample was tested multiple times. Depending on the nature of the solvent used, different dye bands were more or less visible on the results.

Chromatography Process

Unlike chromatography tests in which the target dye is known, here we are looking for the presence of dyes, whatever they may be. While we want to see the presence of lawsone, we also want to see what else may be there. “Henna” products may contain a wide variety of unknown dyes, some of which react to some solvents but not others. While a dye may show up on one type of test, it may not at all in another. Therefore, multiple solvents and solvent strengths should be used.

Pre-trial tests were conducted to determine which solvents and solvent strengths yielded the most useful results. Solvent type and strength also affected how long the sample strips were left in the tank before being removed. Leaving samples in the tank too long can risk dyes being “bleached out” by the solvents so that results became unclear. Pre-trial tests helped to determine the best processing times.

The most conclusive results came from sampling the pastes with the following solvents, strengths, and times:

- 1. 99% isopropyl alcohol for 20 minutes

- 2. 1:1 mixture of isopropyl alcohol and distilled water for 15 minutes

- 3. 1:1 mixture of acetone and distilled water for 15 minutes

It was found that 100% acetone moved so quickly up the paper strips that no useful results were obtained. Therefore, samples on 100% acetone will not be reported in this article.

First, each product was made into a paste following classic henna dye-release methods, which will be described in more detail below. In addition, to account for the possibility of time and acidity breaking down any non-lawsone dyes, each product was tested again by mixing each powder with only distilled water and testing immediately.

Below are the methods and results of each set.

Set 1: Dye Released Paste Samples

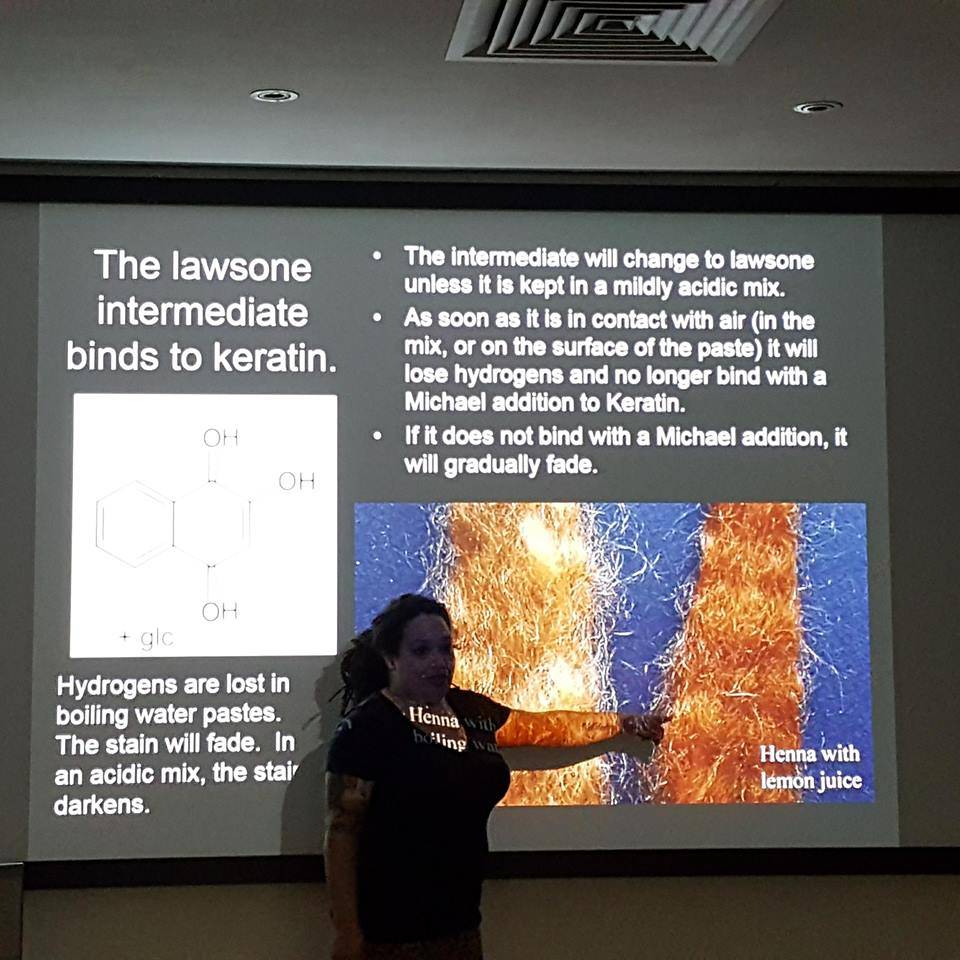

The Lawsone Molecule in Henna

The molecule responsible for the orange/red color achieved by henna is called lawsone. In the henna plant, lawsone precursors exist. When the plant powder is mixed with a mildly acidic mix, the precursors are released as intermediary aglycone molecules in the process that is commonly known as dye release. Aglycones can release in a water-only mixture as well but will oxidize to their final stable state very quickly. The additional hydrogen atoms present in acidic liquid allow the aglycones to stay in their intermediate state longer so that the dye can release more fully before it is applied to the hair. Lawsone in its final state is oxidized and unable to bond to keratin.

The process of oxidation is what gives henna its final color. This is why hair is often lighter and brighter initially after rinsing henna. The color deepens over the course of subsequent days. When the dye molecules in henna paste oxidize before bonding to keratin, this is called demise. This is why pure lawsone on its own is useless as a hair dye.

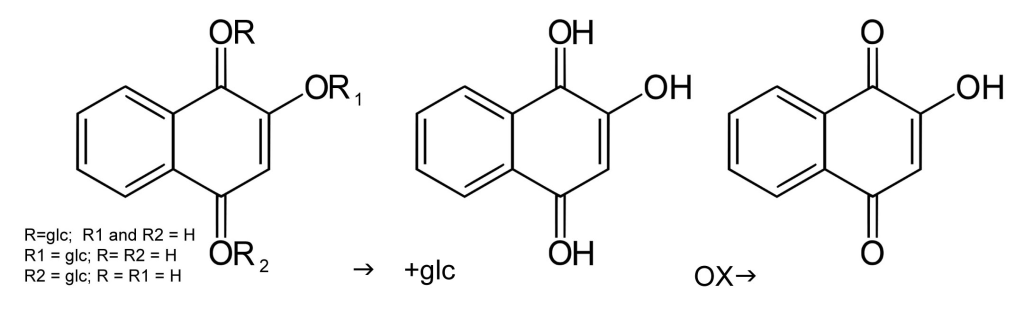

In a mildly acidic liquid, the lawsone precursor (center) is maintained so that it can attach to keratin, after which it oxidizes to its final state (right).

Mixing and Dye Release

Each powder sample was mixed with a prepared solution of distilled water and lemon juice. Lemon juice was added to distilled water until the solution showed a pH of roughly 5.5, as indicated on a litmus strip. The resulting solution was 10 parts distilled water to 1 part lemon juice, or 100ml distilled water and 10ml lemon juice.

Five grams of each powder sample was mixed with the acidic solution to form a paste. The acidic solution was added first to the AS sample to determine an appropriate ratio for creating a paste similar to one that would be used for coloring hair. Thus, the result was 15ml acidic solution for each 5g powder sample*. All prepared pastes were kept in air-tight dark glass jars to prevent excess exposure to oxygen and light. Starting from the moment the final paste was mixed and sealed, all samples were left at 65 degrees Fahrenheit for 12.5 hours for dye release.

*Due to each powder sample varying in particle sift, some pastes were thinner or thicker than others. The variation in paste viscosity may have been a slight factor in test results, but not in any way that could lead to false results.

Set 1 Process

After dye release, a small amount of each sample was applied to paper chromatography strips 0.5 inches from the base of each strip. When not being used, all samples were kept refrigerated at approximately 37-40 degrees Fahrenheit. All samples were tested within 48 hours of dye release. Strips were hung in a glass chromatography tank containing a selected solvent so that the bottom edge of the strips sat just under the surface of the solvent. A glass plate was placed over the top of the tank to reduce airflow. After the determined time, the strips were removed and analyzed.

Below is a short time-lapse video showing how the sample traveled with the solvent. This particular set shows one paper strip for each sample and five strips at a time. One minute of real time is translated to one second of time in the video.

Results

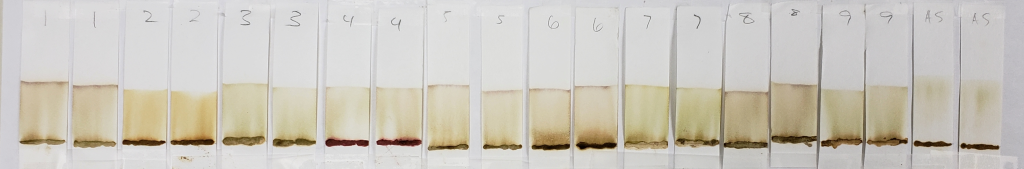

These images show results comparing all paste samples across solvents and times. Samples are all tested numerous times, but for the sake of visual reporting, one or two paper strips of each sample for each test were chosen based on which were the most representative of the group. Outliers were those whose results appeared least like the others, most likely due to an odd variation in the paper strip causing inconsistent solvent wicking. These were disregarded. The remainders showed consistent results with little variation.

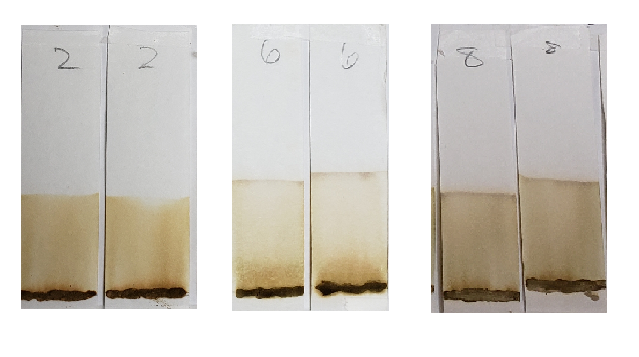

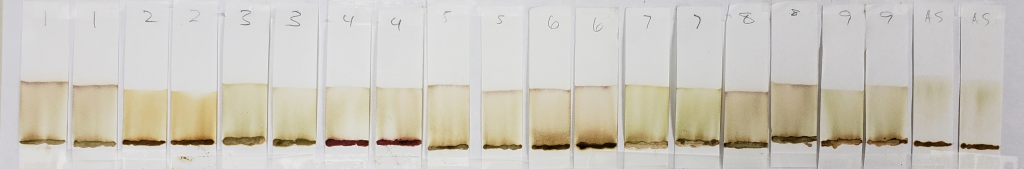

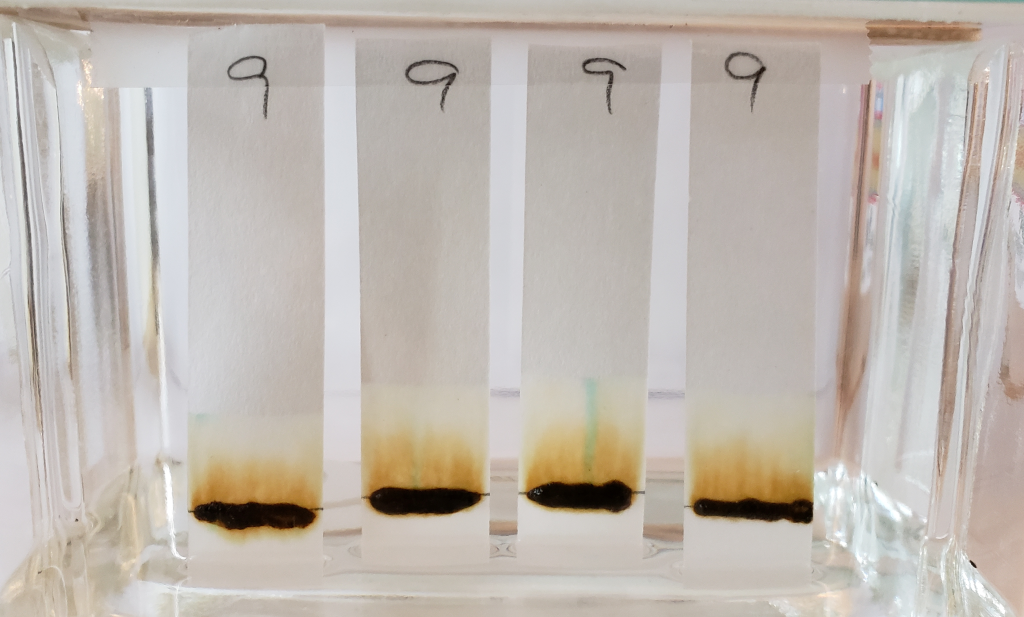

99% Isopropyl Alcohol for 20 Minutes

One can see that all of these strips show mostly pale dyes that range from green to orange to light brown, and that few show clear dye bands below the solvent front. In the world of chromatography, most of these would not be usable results. However, for our purposes, they are interesting. This is because we know that lawsone does not show much color in its intermediate aglycone state. The presence of water can cause oxidation of the aglycone to its stable final form. So, when using an anhydrous solvent, it would be expected that the dye does not turn up bright orange. If it does, it might suggest that final-state (oxidized) lawsone was present in the product, or that an orange dye other than lawsone was added to the product.

If you are familiar with the process of coloring your hair with henna, you will know that the final color result takes a few days to mature. The lawsone molecule exists in a precursor state called an aglycone when it is mixed in an acidic paste and allowed to dye release. As long as the paste is not exposed to oxygen, and if it is not left to demise, most of these molecules remain aglycones. It is through the process of bonding to the keratin in your hair, and to the oxygen molecules in the air that they become stable lawsone molecules, and you see the deeper color. This is also why henna paste applied to the skin is left for several hours, and the design deepens over the following days.

BUT, if a lower quality henna powder is “fixed” with added lawsone, that lawsone would be the stable-molecule type. This is sometimes done by henna sellers to make the product appear to have a higher lawsone content, or as an attempt to make the product more effective. Manufacturers and distributors who do not have a solid understanding of the chemistry of henna do not realize that adding lawsone will do nothing to the efficacy of the product. Stable lawsone will not bind to the hair because it has lost the hydrogens necessary to create a bond. Only the aglycone lawsone molecules released from henna powder by an acidic liquid have the ability to bind to keratin.

One can see that out of all of the other samples, AS (shown above) is one of the palest, nearly a yellow-green color, and almost seems to form a band below the solvent front. Virtually no dye remains near the application point. This indicates two things: first, that there was little to no oxidized lawsone in the paste sample. Second, the fact that the block of space between the paste application line and the solvent front is so “clean” suggests that there is only one type of dye at one point of chemical state. We know that this dye is lawsone in an aglycone state. The more dyes involved, the muddier the strip may appear, as it will show evidence of several observable dyes, or dyes in several molecular states. In fact, even a product that contains a nothing else but a blend of several different hennas would most likely show variation due to those dyes being just slightly different from each other.

Samples such as #2, 6, and 8 are more orange, and also show darker bands right above the sample application sites. The muddy brown band is very prominent in #6. In fact, all samples except for AS showed some level of banding that hugged the paste sample when tested with 99% isopropyl alcohol. This happens when there is a dye present which does not move well with the selected solvent and which prefers to stay low with the sample. Lack of dye movement in itself is not necessarily bad, and is simply indicative of the relationship between the dye and the solvent; however, because we can see that this did not happen with the AS sample, we can guess that those other powders contained something that AS did not.

Both #2 and #6 are particularly orange, which again suggests the presence of either added lawsone or another dye that comes up orange under these conditions. If we revisit the image of those powders prior to mixing, sample #2 especially is of a darker color. #6 and #8 are lighter, but still border on what would be a normal color for henna powder. It is possible that these three products have added lawsone or another orange dye.

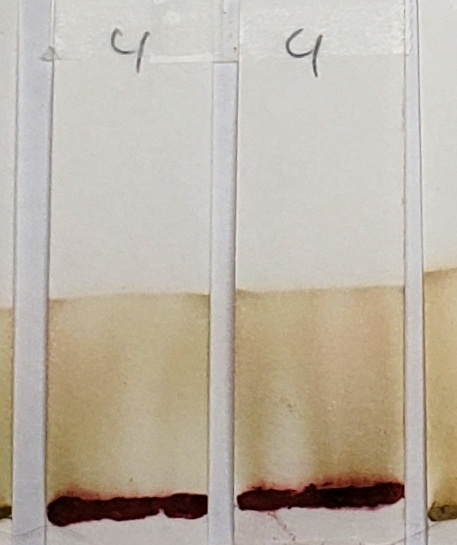

#4 is very interesting, and will continue to be interesting as we go along. There is very clearly the presence of a red dye that is not lawsone. It is a vivid red which appears just above the application point. If you revisit the earlier sections of this article which show the powders and pastes, #4 is a vivid red color as both powder and paste.

#9 shows the presence of a green-blue dye which appears as faint streaks closer to the base of the strips. The solvent front also shows the same color near the edges. In addition, there is a deeper, brown band that stays just above the application point.

#7 also shows a faint green tint similar to #9, but there are no noticeable blue-green bands. Some green tones can be expected due to the presence of chlorophyll in the plant powders. Therefore, a green color does not guarantee the presence of an added dye. However, the blue-green streaks present in sample #9 are not consistent with chlorophyll.

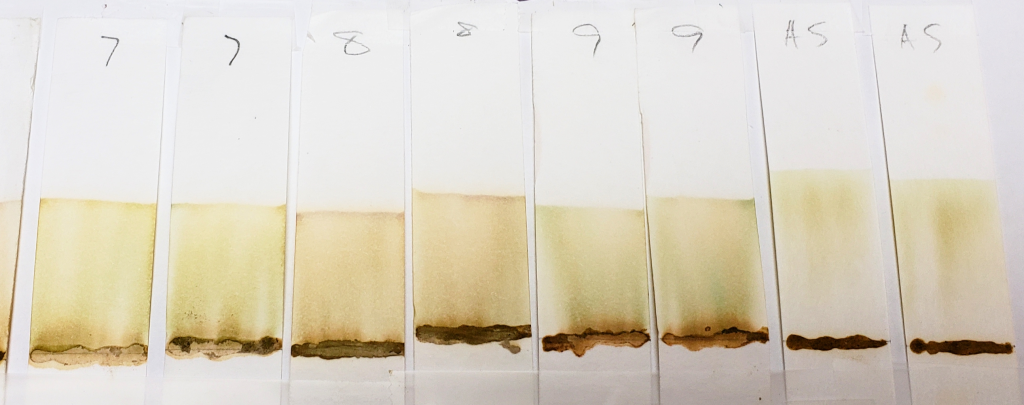

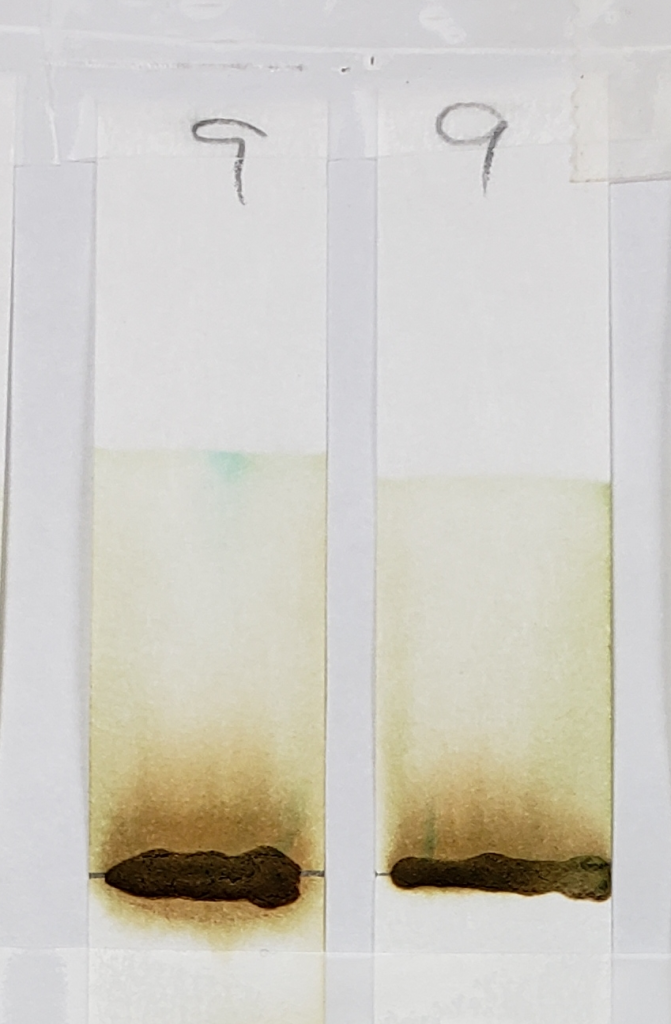

1:1 Dilutions for 15 Minutes

In comparison, dye bands were more visible when pastes were tested with equal parts solvent and distilled water. This is because water causes the lawsone dye to oxidize, turning the dye a deeper orange. In fact, the dye stained the paper strip as it moved upward with the solvent.

Water alone was not an effective solvent because the dye did not travel with it quickly enough. Pure solvent, on the other hand, pulled the dye too quickly, leaving little to no banding, as was shown by the 99% isopropyl alcohol set. By combining distilled water and solvent, both dye oxidation and dye movement was achieved in a way that showed visible dye bands.

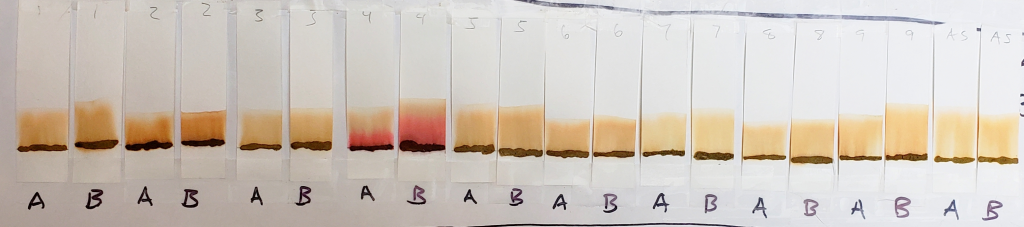

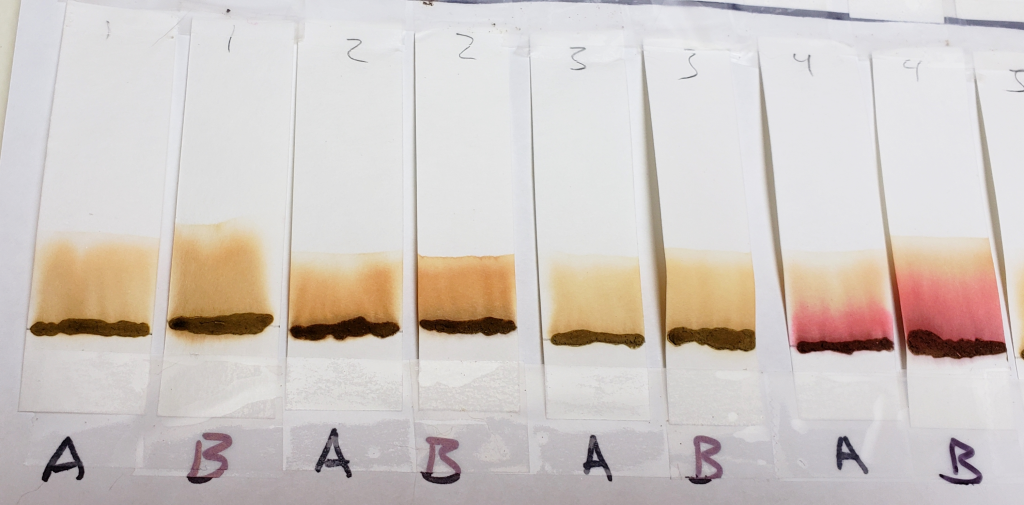

In the image above, A and B labels indicate results for 1:1 isopropyl alcohol/water and 1:1 acetone/water respectively. Both were left in the tank for 15 minutes. Results were generally similar for both solvent dilutions.

In comparison to 99% isopropyl alcohol, results from 1:1 dilutions were deeper orange with dye bands visible on most samples. While they are still faint, the banding for lawsone can be seen as stripes of deeper color just below the solvent front.

One can see that the AS sample remained relatively pale, and that the dye seemed to move more cleanly away from the application line, leaving lighter streaks where little or no dye stained the paper.

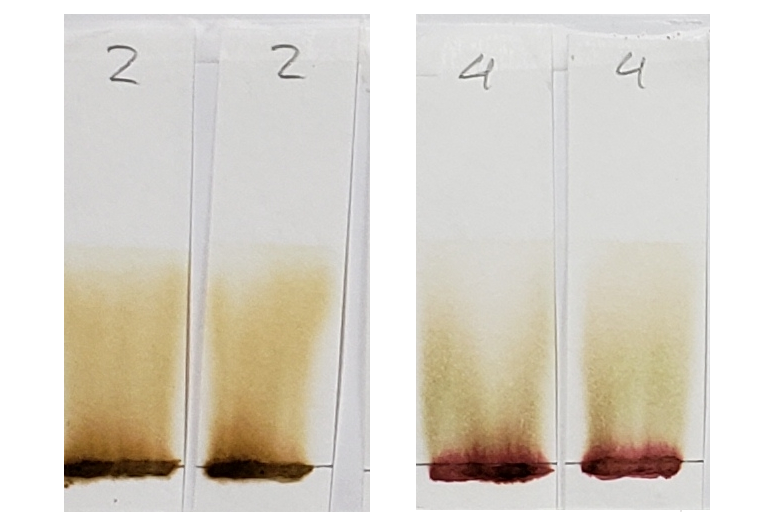

Sample #4 clearly shows the presence of a red dye along with lawsone. There is a bright red band that stays near the application line. The band moved higher in the 1:1 acetone/water sample, but both tests show separate red and orange bands.

Sample #2 shows a significantly darker dye which creates a nearly solid stain from application line to solvent front. There is a band near the top which could be lawsone. If you look closely, there is a slightly deeper orange band that stays near the application line. This suggests that there may be an additional orange dye along with lawsone. Sample #1 also shows a darker color in comparison to other samples, which may suggest the presence of additional dyes.

Another notable detail is the color of the paste samples at the application line after processing. Many are bleached out as the solvent pulls the dye from the sample. The AS application line is the palest. Samples #2 and #4, however, remained very dark. This is another reason to believe that additional dyes besides lawsone were present.

Sample #9, which show blue-green dye streaks when processed with 99% isopropyl alcohol, changed significantly when processed with 1:1 dilutions. Most likely the faint blue-green dye was overpowered by the orange stain.

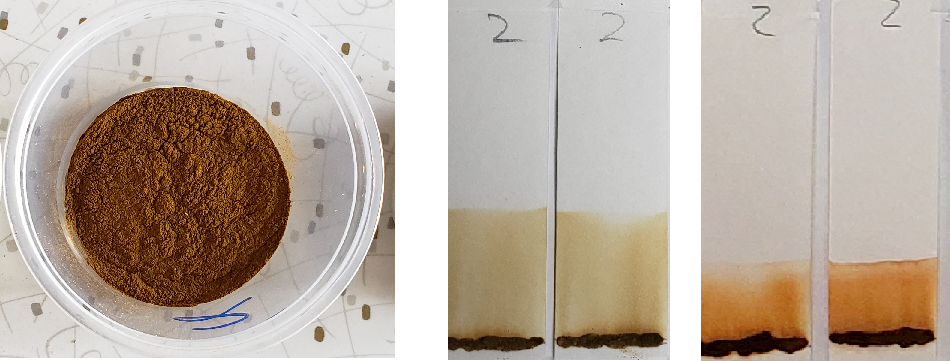

Set 2: Powder and Water Samples

It is important to note that all samples were treated as if they were 100% pure henna powder– that they contained no additional dyes or acids, and that they would require an acidic solution and dye release time. This was done to keep results consistent.

However, there was the possibility that added water-soluble dyes were present which could have been broken down by the acidic solution, or by sitting too long after mixing. Thus, the same process was repeated with paste samples made from just distilled water. These samples were tested immediately after mixing, with no wait time.

Theoretically, this set would show very little lawsone especially in the 99% isopropyl alcohol condition, as the henna would not have had much chance to release lawsone in its aglycone precursor state. The 1:1 dilutions may still provide an environment for a fast release/oxidation of lawsone, but some additional dyes may be better seen than in Set 1, if they were affected by the acidity and/or 12 hour wait.

For each sample, 1g powder was mixed with 3ml distilled water. The paste was stirred until a uniform consistency was achieved, then a small amount was immediately applied to paper chromatography strips and tested with the same solvents and times as Set 1. To repeat, the conditions were as follows:

- 1. 99% isopropyl alcohol for 20 minutes

- 2. 1:1 mixture of isopropyl alcohol and distilled water for 15 minutes

- 3. 1:1 mixture of acetone and distilled water for 15 minutes

New paste was made for each solvent condition so that each sample was tested immediately after mixing with water.

Results

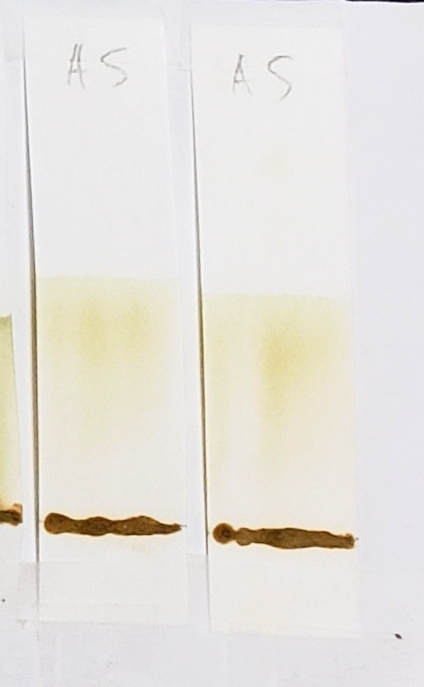

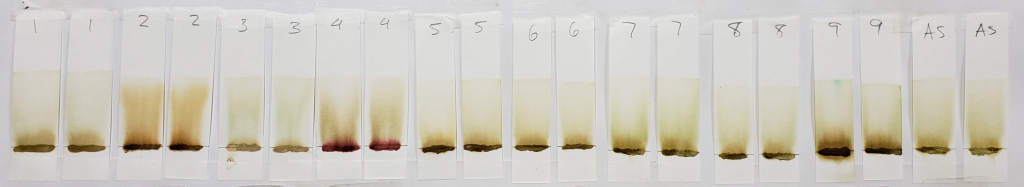

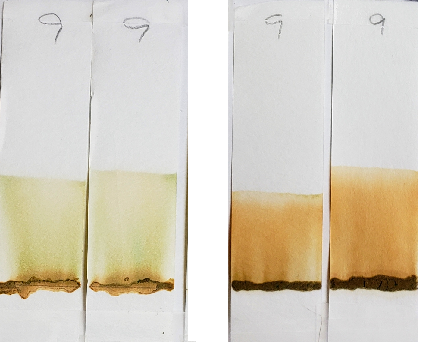

99% Isopropyl Alcohol for 20 Minutes

The image above shows results for powders mixed with distilled water only and immediately tested in 99% isopropyl alcohol. Unlike the results of dye-released pastes tested with 99% isopropyl alcohol, samples mixed with only water showed consistent bands rising to just above the application point. Less dye traveled upward with the solvent, leaving paler tones near the solvent front. Below is the image for dye-released pastes tested with 99% isopropyl alcohol for comparison.

Notable results for this set are those of samples #2, #4, and #9.

Sample #2 appears more vividly orange than all other samples. This occurs in both the dye-released set and the water-only set. There is strong evidence for an added orange colored dye, lawsone or otherwise.

Sample #4 shows the same red dye that has been apparent in all tests. Because more red dye traveled with the solvent in the water-only set in comparison to the dye-released set, this is most likely a dye which is affected by pH and/or time.

The faint green-blue dye that was noticeable in previous tests of sample #9 is particularly present in this condition. It was especially noticeable during processing. In the image below, all four strips show streaks of green-blue dye traveling upward with the solvent. The clearest is the strip second from the right.

After the strips were left in the glass tank for a full twenty minutes, the dye had collected at the solvent front. Some dyes streaks can also be seen rising just a few millimeters out of the application point. Particles of the same color can also be seen within the paste. It is clear that the green-blue dye is some form of powder or crystal mixed into the product.

1:1 Dilutions for 15 Minutes

The paper chromatography results using equal parts water and acetone, and equal parts water and isopropyl alcohol appeared very similar to the results of the dye-released pastes tested with the same dilutions. Nothing additional was revealed that was already noted in the earlier tests. This may be because the distilled water present in the diluted solvents was enough to reveal water-soluble dyes.

Discussion

The purpose of this article was first: to observe and report the visible qualities of each product, such as the product packaging, and the color, scent, and texture of the product both as a dry powder and after being mixed with liquid; and second: to determine the existence of dyes other than lawsone or lawsone precursor molecules through the use of paper chromatography.

None of the methods used in this article can definitively determine the safety or quality of a product. Thus, it is not our intention to rate, review, or suggest any product outside of the Ancient Sunrise brand. The fact that some products appeared similar to pure henna does not mean that they were void of additives or adulterants not shown by these tests. Paper chromatography cannot show the presence of non-dye chemicals such as pesticides. Given those disclaimers, let’s jump into what was observed.

The presence of red, orange, and green dyes in some samples indicate that those products included additional ingredients besides pure henna powder. While all of the samples tested showed the presence of some lawsone, many samples displayed results inconsistent with the AS sample which we know to be 100% pure henna powder. When dye-released pastes were tested with 99% isopropyl alcohol, all samples except AS showed dye that did not move with the solvent, staying low to the application line. Some samples were much darker in color, which is inconsistent with the pale yellow-green color that would appear with lawsone in a precursor state. It is unclear if some samples included oxidized lawsone, and whether that lawsone was added during manufacturing or if other conditions such as the age or storage of the product may have led to the presence of oxidized lawsone.

Sample #2 showed a very deep orange color in all solvent conditions. When tested with 99% isopropyl alcohol, the deeper color dye was visible just above the application site. In 1:1 dilution tests, the dye traveled further up the strip, staining the strip orange from application to just under the solvent front. This suggests that there is an added water-soluble orange dye present in sample #2.

Blue-green dye was visible in sample #9 when tested with 99% isopropyl alcohol. In diluted solvent conditions, the blue-green dye was no longer visible. This type of dye was most likely added to give the powder a greener color, rather than to affect the color outcome on the hair.

Right: Sample #9 tested with 1:1 dilutions. The lawsone staining overpowers blue-green dye visibility.

Because there is a marketing claim that a greener henna powder is fresher, adding green dye to henna powder is not an uncommon practice. Detailed information about henna powders “polished” with green dye can be found on page 39 of Chapter Four: Henna Science and Microscopy. Ironically enough, sample #9 was among the darker colored powders and pastes in the group, so the addition of green dye did not seem to do what it intended. Below is an image at 60x magnification of a henna powder which shows added green dye.

Limitations and Considerations

Paper chromatography is only one type of chromatography, and not as exact as methods accessible in a certified laboratory. High-performance thin-layer chromatography, for example, is capable of separating dyes into much clearer bands, and then a scientist can calculate and compare the distance of those bands between the application point and solvent front to determine more about the nature of each dye. In many cases, reactants can be applied to chromatography results to cause substances to be visible if they are not already. Access to such methods would have been beneficial. An example of high-performance thin-layer chromatography can bee seen on page 22 in Henna Science and Microscopy.

Additionally, some samples varied in age, which can affect the quality of a powder to some degree. That being said, pure henna products have a shelf life of several years as long as they are kept sealed and in a cool, dry environment. Because the products tested may have contained additional unknown ingredients, it is difficult to say whether those specific non-henna ingredients may have broken down or changed with time.