Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Sample Selection And Label Analysis

- Powder and Paste Qualities

- Chromatography

- Results

- Discussion

- Limitations and Considerations

Introduction

This article is the second in a series comparing products sold as henna for hair. The purpose of this series is to describe and compare henna for hair products commonly found online on sites such as Amazon or eBay as well as in ethnic grocery stores, health food stores, and import stores in the USA.

Part One introduced objectives and methodology. It compared products that are marketed as either “pure henna,” or which are described as henna blended with other natural herbs for a red hair color result. To read part one, click here.

This article, Part Two, will continue using the same format as Part One. Part Two examines “henna for hair” products claiming to color hair brown or brunette. First, product labels are analyzed. Second, the plant powder is described in terms of texture (sift), color, and odor. After mixing, the qualities of the resulting pastes are also described. Finally, each past sample is tested using paper chromatography to determine the presence of added dyes. The products are compared to Ancient Sunrise pure henna and indigo powders.

Many products labeled and sold as henna contain additional ingredients, either plant-based or synthetic. Products whose labels claim to be “100% natural” or who use similar terms often fail to disclose all ingredients. Many products are imported from countries whose regulations are less stringent or loosely enforced. Additionally, products vary in quality. Poor sift results in powders containing larger pieces of plant particulates as well as sand. Products with poor packaging will become stale more quickly, causing the dye to be less effective. In many cases, products marketed as natural and safe in all actuality contain added dyes such as azo-dyes, metallic salts, and parapheneylene-diamine (PPD). To learn more about the difference between BAQ henna, compound henna, and other products claiming to be henna, read this article.

The FDA has a standard for henna and products entering the United States labeled as a “henna” hair coloring product. These guidelines do not appear to be regularly enforced as are regulations for products labeled as henna for use on skin. The result is that many products labeled as “henna for hair” which do not meet the guidelines make their way into the United States with relative ease.

The FDA forbids the sale of and is empowered to confiscate of any henna product labeled for skin use, or products showing images of henna used on the skin. Customs and border protection is empowered to search the importing company’s website to determine if henna is intended for use on skin, and may seize and destroy henna that appears to be imported for use on skin.

“Black henna,” or products labeled as henna containing PPD, have been known to cause skin reactions and sensitization. For more information about black henna, read the articles “Henna is Not Black,” “What You Need to Know About PPD,” and Chapter One of the Ancient Sunrise E-book.

The purpose of these studies is to determine the quality of those products in comparison to Ancient Sunrise® Henna for Hair products and to test for the existence of dye additives. This series investigates the following categories:

- Part One: “Pure” henna, herbal henna mixes, and red result henna for hair products

- Part Two (this article): Brunette result henna for hair products

- Part Three: Black result henna for hair products

Premixed “Henna for Hair” Products

All of the products analyzed in this section claim to contain a blend of multiple plant dye powders and in some cases additional synthetic ingredients. All claim to contain henna. Most claim to contain indigo. Because henna and indigo require separate mixing and dye release processes, Ancient Sunrise packages plant powders separately. The most effective method for mixing henna and indigo involves mixing henna first with an acidic component and allowing time for dye release, normally 8-12 hours at room temperature. Indigo does not require an acidic component nor dye-release time because the dye releases and demises rapidly. It is mixed with only water and then combined with dye released henna just before applying to the hair. To learn more about the proper way to mix henna and indigo for brunette results, read this article.

Premixed “henna for hair” products may provide a simpler mixing process but in turn sacrifice full coverage and color permanence. Most of the products in this article recommend mixing the powder with water to form a paste and applying immediately. This is most likely due to indigo dye’s rapid demise. Without proper dye-release, the lawsone and indigo dye molecules will not bind to the hair as effectively. The result may be lighter than desired and will fade over time.

Finally, many of the following products report a number of “ayurvedic herbs” in their ingredients in addition to plant dye powders. Most of these herbs do not affect the color result but claim to condition the hair and scalp and/or promote hair growth. Please note that this article is not meant to support or deny the effectiveness of these claims. Descriptions of the herbs should not be interpreted as recommendations.

Sample Selection and Label Analysis

Eight “henna for hair” products were selected for this study based on the following criteria:

- 1: The product is marketed as a “henna for hair” product or a plant-based product containing henna which is meant for coloring hair.

- 2. The product claims to color hair a shade of brown or brunette.

The traditional method for achieving a brunette result using plant dye powders involves a combination of henna and indigo. Many of the products selected for this article include both henna and indigo in their ingredients disclosures. These products will be compared with Ancient Sunrise Rajasthani Twilight Henna and Ancient Sunrise Zekhara Indigo plant dye powders.

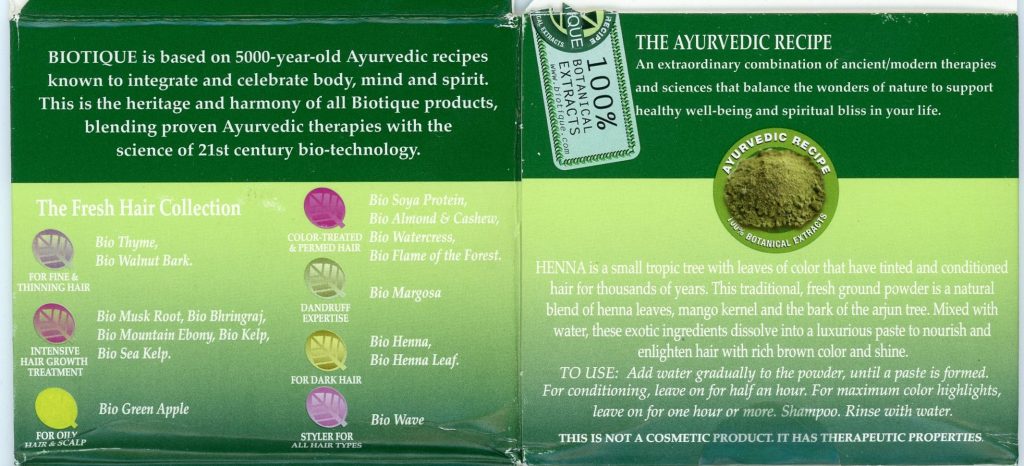

Below are the images of the labels for the selected samples. In the future, each sample will be referred to by its assigned number.

#1

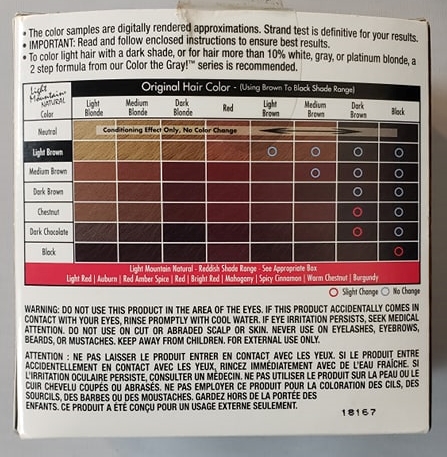

This product is made in the United States and is widely available at health stores and online. The labeling and packaging are thorough in comparison to many “henna for hair” products and are reminiscent of the labeling and packaging of box hair dye. The color on the label is “chestnut.”

The ingredients listed are “henna, indigo, centaurea, rhubarb, and beetroot.” Centaurea, also known as cornflower, can be used as a natural blue dye for fabric. Whether or not it is an effective dye for hair is unknown. Most natural fabric dyeing processes involve boiling and the use of a mordant. Similarly, rhubarb and beetroot have been used to dye fabrics yellow and red respectively. To learn more about what ingredients do or do not effectively color hair, read “Does it Dye Hair?” Rhubarb is acidic and may aid in dye-release, but the instructions do not include a dye-release period.

The internal pamphlet offers detailed instructions and information regarding application, patch testing, and a warning against use near the eyes. The instructions are to mix the powder with water, apply, and leave for one hour.

#2

This product is made in India. It claims to be for dark hair and gives hair a “rich brown color and shine.” The ingredients listed are as follows: “Mehndi (Lawsonia alba), Aam Beej (Mangifera indica), Neem (Azadirachta indica), Arjun (Terminalia arjuna), Gambhari (Gmelina arborea), Daruhaldi (Berberis aristata), Kikkar gaund (Acacia arabica).” While henna is listed as the first ingredient, indigo is not mentioned at all.

The product is described as “ayurvedic,” which is a term relating to an alternative system of medicine often involving a number of herbs native to South Asia. Aam beej is mango seed. This is not a dye but is meant to condition hair. Ancient Sunrise supplies mango seed butter here. Neem is another popular ayurvedic herb used for hair conditioning in either a powder or oil form. Neem does not dye hair. Arjun is an ayurvedic herb. It appears to have potential dyeing properties on fabric but needs a mordant. Its ability to dye hair is unknown. Gambhari, also known as English Beechwood, is used in ayurvedic medicine and claims to condition hair and stimulate growth. It does not dye hair. Daruhaldi is also known as Indian Barberry. The plant is used to dye fabrics and tan leather due to its high level of tannins. Its effectiveness in coloring hair is unknown. Kikkar gaund, also known as Gum Arabic, is both eaten and used in topicals. Because it contains a high amount of mucilage, it can act as a thickener or binder when mixed with water. It is a common ingredient in both cosmetics and food. It does not have dye properties.

Like sample #1, this product’s instructions recommend mixing the powder with water. It recommends leaving the paste in the hair for half an hour for conditioning, and one hour or longer for “maximum color highlights.” In one Amazon review, a customer said that the product made her hair “really red.” It is likely that the absence of indigo and the ineffectiveness of the other herbs meant for coloring caused the result to be red rather than brunette.

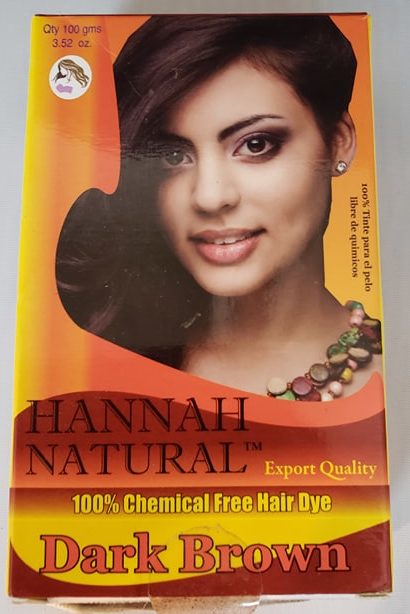

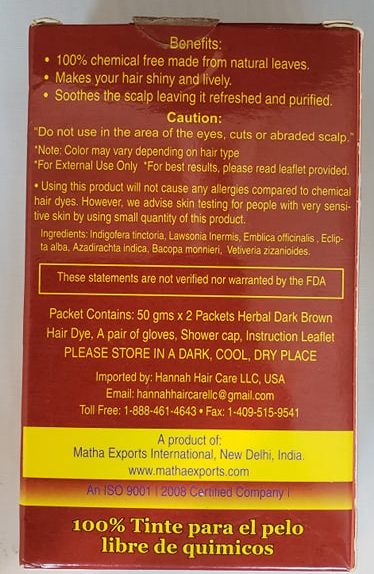

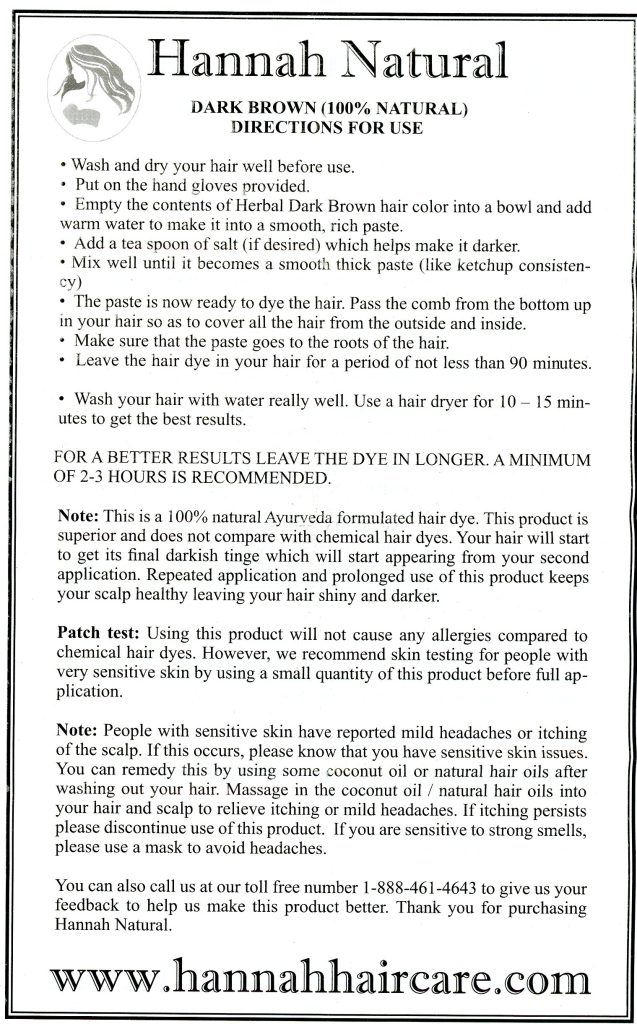

#3

This product is from India. The color result advertised on the label is “dark brown.” The ingredients are as follows: “Indigofera tinctoria, Lawsonia Inermis, Embelica officianalis, Eclipta alba, Azadiracta indica, Bacopa monnieri, Vetiveria zizaniodes. The first three ingredients are indigo, henna, and amla powder respectively. A dark brunette mix should have a higher proportion of indigo to henna. Amla powder functions as an acid and aids henna/indigo mixes in binding to the hair effectively for a darker result. Eclipta alba, also known as bhringraj, is an ayurvedic herb known for its potential hair growth properties. Azadiracta indica, as mentioned before in sample #2, is also known as neem. Bacopa monnieri, also known as brahmi, is an ayurvedic herb that claims to promote hair growth. Finally, vetiveria zizaniodes is also called vetiver, which is another ayurvedic herb meant to condition hair and stimulate growth. Vetiver has a pleasant scent. Ancient Sunrise carries a soap bar which contains cardamom and vetiver. Except for the initial three ingredients, the remaining reported ingredients are ayurvedic herbs without dyeing properties.

The package includes gloves, a plastic cap, and an instructional pamphlet. It includes warnings about sensitivity and instructions for patch testing. The product warns about potential headaches and itching. This is most likely in reference to the reaction to indigo powder, which causes some people to have discomfort. To learn more about plant dye powder allergies, read “Plant Dye Powders and Seasonal Allergies.”

The product recommends using coconut oils or other oils to relieve itching or headaches. Itching after using plant dye powders is often due to acidity or failure to fully rinse out all residue. Because this product contains ingredients other than henna and indigo, it is difficult to determine if something else may cause such a reaction. To learn more about dryness and itching after using plant dyes, read “Why Hair Feels Dry After Henna and How to Fix It.”

The instructions recommend mixing the powder with warm water and a teaspoon of salt. Ancient Sunrise recommends adding salt to indigo paste to help the dye bind more effectively to the hair. Because this product is a premixed powder, it is not possible to mix salt with indigo paste separately before adding it to the henna paste. This product recommends leaving the paste in the hair for 2-3 hours. It also recommends using a hairdryer after rinsing. Heat can help deepen the resulting color. However, as with the other samples, this product does not recommend a dye-release period.

#4

This product is from India. The ingredients are listed as follows: “Mehindi, Harred, Berhera, Amla, Shikakai, Coffee, and other Herbal…”

Mehindi is another word for henna powder. Harred, also known a harad or haritaki, is an ayurvedic herb with a variety of reported health benefits. Its scientific name is Terminalia chebula. It does not dye hair. Berhera (Terminalia bellerica) goes by many names including behara and belleric. It appears that the combination of haritaki, belleric, and amla powders is often known as “triphala,” a popular ayurvedic herbal remedy. Amla has been mentioned before and is an effective dye-release agent as well as a popular ayurvedic herb. Shikakai is an herb used for cleansing and conditioning hair. The addition of coffee is most likely for the purpose of color, but coffee is not an effective hair dye. Katha (Acacia catechu), also known as catechu, is an herb used both in medicines and in food as a spice. It is used as a dye for wool, silk, and cotton. Its effectiveness as a hair dye is unknown.

The ingredients list does not include indigo powder. Overall, the product appears to be henna along with a number of ayurvedic herbs, with coffee and katha potentially affecting the color result.

This product recommends mixing the liquid with “light hot water” (warm water?) in an iron bowl and letting it sit for 2-3 hours. The use of an iron bowl when mixing henna is an old tradition and is meant to affect the dye-release in a way that causes a darker result. It is now known that using iron is not necessary. There are no additional instructions regarding preparing the hair, applying, processing and rinsing. There is no inner pamphlet, standard warnings or patch test instructions.

The product claims to contain no chemicals or dyes and claims to cause zero side effects. Most likely it means no synthetic dyes. Caffeine is transdermal. The addition of coffee in this product may cause jitters and headaches.

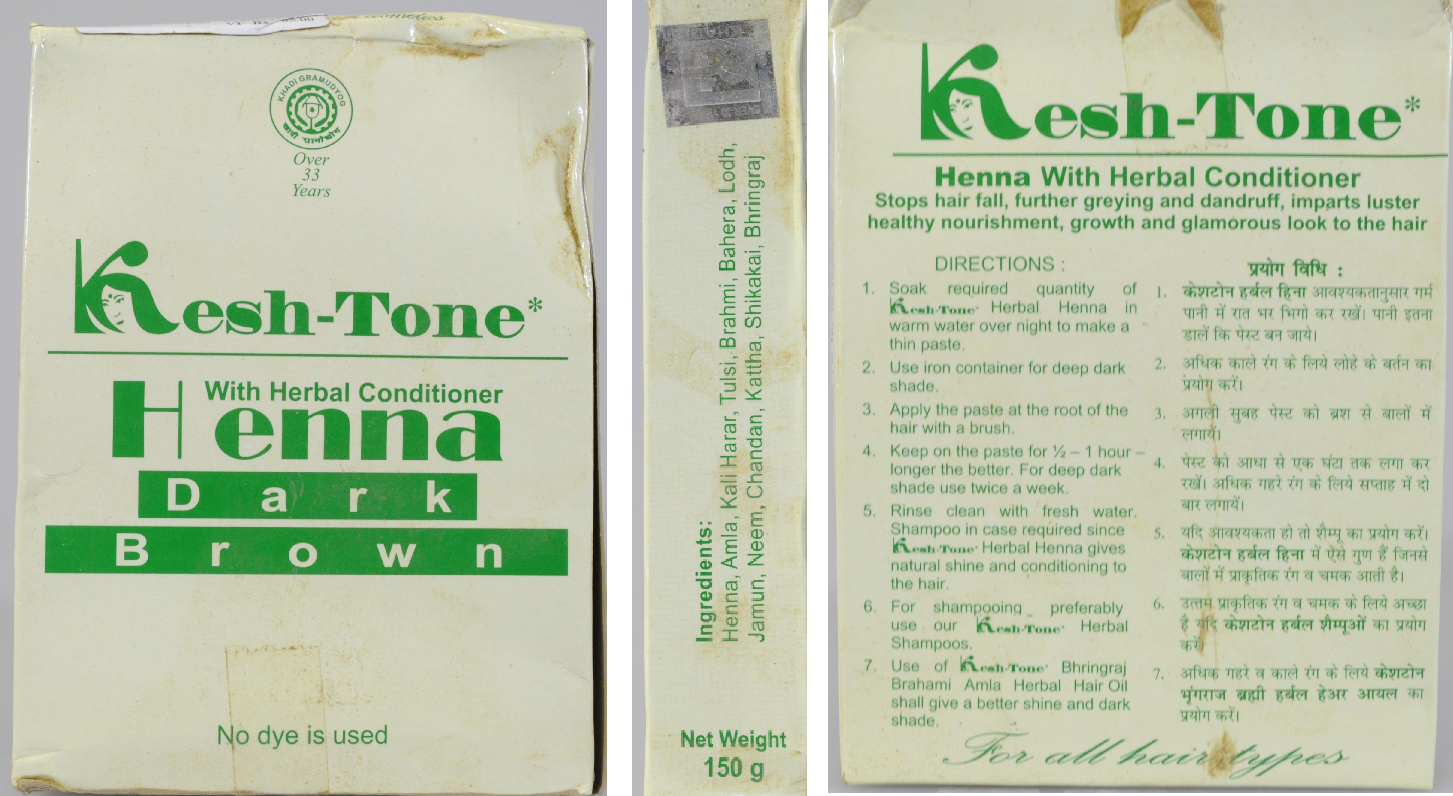

#5

This product labeled as henna with herbal conditioner for a dark brown result. The country of origin is India.

The ingredients are listed as follows: “Henna, Amla, Kali Harar, Tulsi, Bahera, Lodh, Jamun, Chandan, Kattha, Shikakai, Bhringraj.” Amla, shikakai, bahera, and bhringraj have been described previously in this article.

“Kali Harar” seems to be a misprint of “Kali Harad,” also known as harad , harade, or harred. This is the same herb as haritaki, which has been previously described. Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) is also known as holy basil. It is an ayurvedic herb used for many purposes. Lodh (Symplocos racemosa) is a tree used for ayurvedic medicine and whose bark is used for yellow dye. Its effectiveness as a hair dye is unknown. A brief account of the plant being used for dyeing hair yellow can be found here. Jamun (Eugenia jambolana) is also known as black plum. The bark and fruit are used in avurveda. While jamun does not appear to have dyeing properties, it does contain anthocyanins which may aid in cooling or neutralizing the brighter tones from henna. Ancient Sunrise Nightfall Rose fruit acid powder is made from the purple aronia fruit also contains a high amount of anthocyanins. Ancient Sunrise Nightfall Rose Powder can be found here. Chandan is also known as sandalwood. It can be used to dye wool or fabrics red or brown but requires boiling and a mordant. Its effectiveness as a hair dye is known. Kattha is another name for katha, or catechu, which is mentioned in sample # 4.

The instructions for this product recommend mixing the powder with water and letting it sit overnight. This product does not appear to contain indigo. Because amla and other fruit powders are included with henna, the powder may be acidic enough to be able to dye release overnight when mixed with water. Like other samples, the product recommends using an iron container, which is not necessary. The instructions recommend leaving the paste in the hair for ½ an hour to 1 hour or longer.

#6

This product is assembled and sold by an American company. The origins of the plant dye powders is not listed. This brand is commonly found in health stores in the US. The outer packaging reports that the ingredients are certified organic and contain no ammonia, peroxide, metallic salts, or PPD.

The ingredients are as follows: “Indigofera tinctoria (indigo) leaf powder, Cassia auriculata (senna) powder, Lawsonia inermis (henna) powder, Phyllanthus emblica (amla) fruit powder.” All reported ingredients save for amla powder are plant dye powders. Amla functions as an acidic component for dye-release and also assists in neutralizing warmer tones from henna and cassia.

The labeling and insert include warnings and patch testing instructions required from the FDA. Unlike some previous products in this article, this product recommends against using any metallic container or mixing implements. Metal such as stainless steel is fine to use when mixing henna. It does not cause any issues.

The instructions recommend mixing the pre-mixed powder with boiling water and applying it to the hair once it is cool enough. It claims that its “finer mesh botanicals do not need to cure.” That implies that only coarser sifts require dye-release time, which is untrue. The process of dye release involves the lawsone precursor molecules migrating from the dry powdered plant leaves into an acidic liquid environment where the molecules remain stable until the user is ready to apply. The boiling-water method will force henna to dye-release rapidly but the resulting paste will contain fewer stable aglycones and will therefore be weaker. It will often result in lighter, brassier, impermanent results.

Additional recommendations involve replacing some of the boiling water with egg or yogurt (“for extra conditioning,”), lemon juice or chamomile tea (“to bring out golden highlights”), hibiscus tea (to “intensify reds”) and coffee (“to enhance brown tones”). We know that these ingredients have little to no effect on the hair color result. Lemon juice can in fact cause the resulting hair color to oxidize much darker over time. Egg and yogurt will coat the hair and inhibit dye uptake. Coffee will not permanently color hair brown and will cause jitters and headaches. To learn more about what not to add to henna, read “Don’t Put Food on Your Head” and “Does It Dye Hair?”

#7

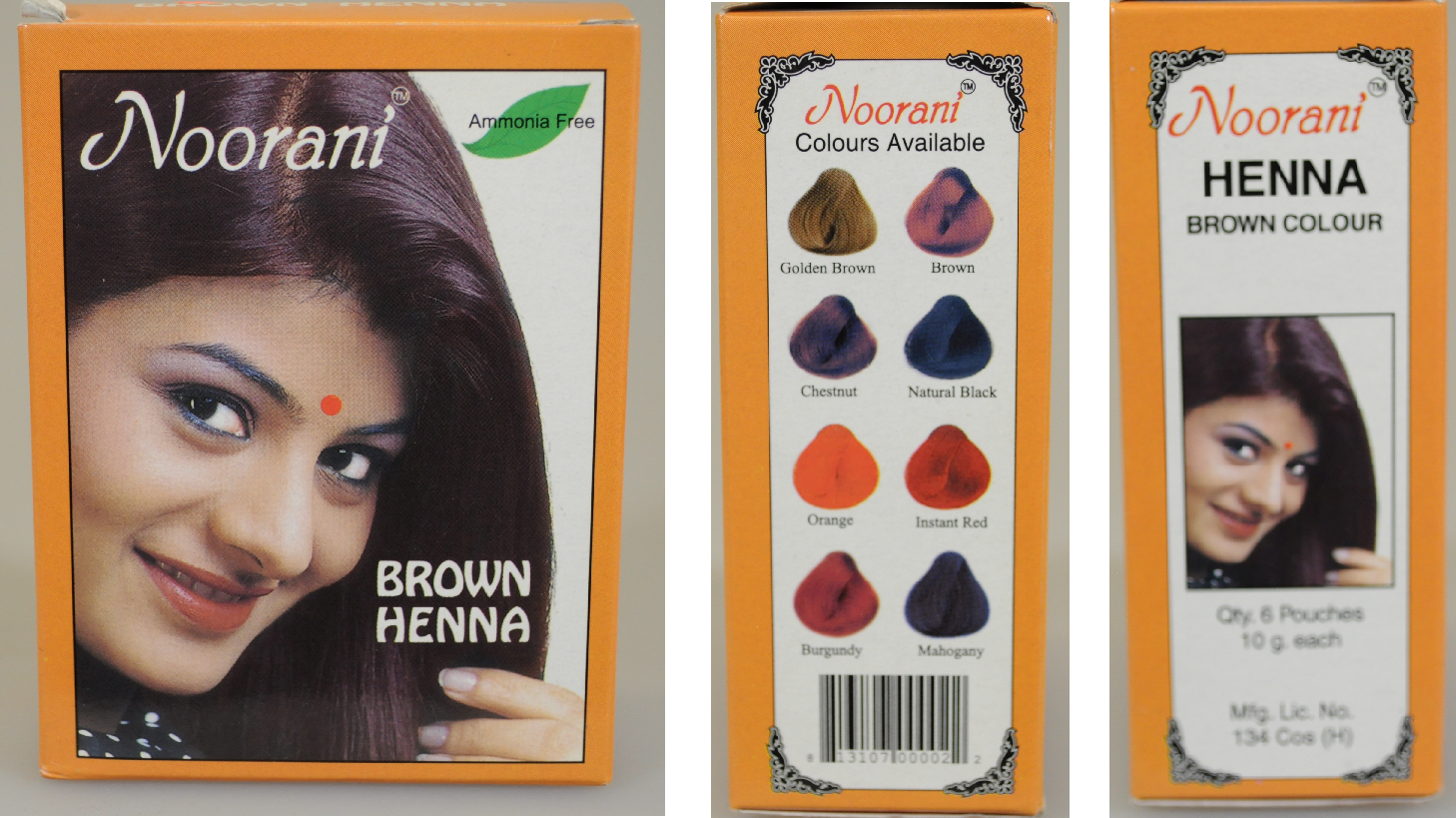

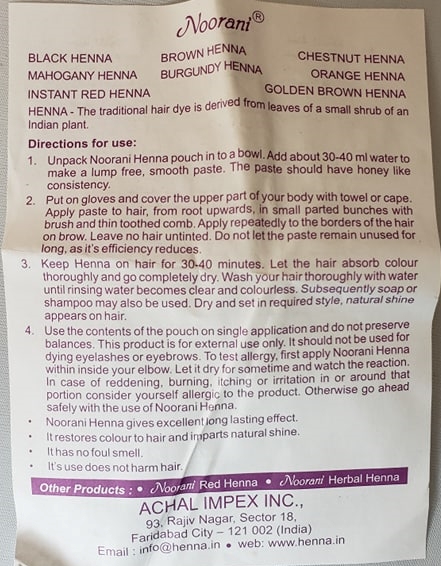

This product is from India. It is labeled as “brown henna.” A single box contains six thin, flat packets. Each packet further contains a small foil pouch containing 10 grams of product and an instructional paper. Each pouch is meant to be enough for one application.

The instructions recommend mixing a packet of powder with 30-40 ml of water (roughly two to three tablespoons). The paste is then to be applied and left in the hair for 30-40 minutes.

There is no ingredient disclosure in any part of the packaging. The small amount of product per application in combination with the short processing time suggests the presence of PPD or other synthetic dyes.

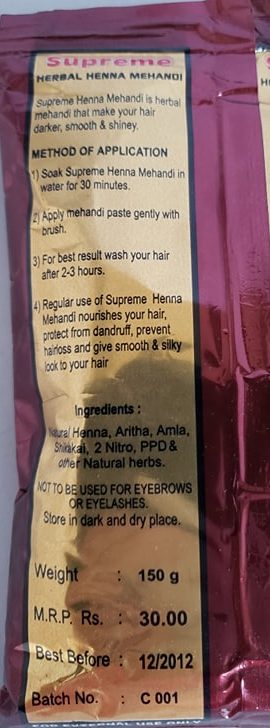

#8

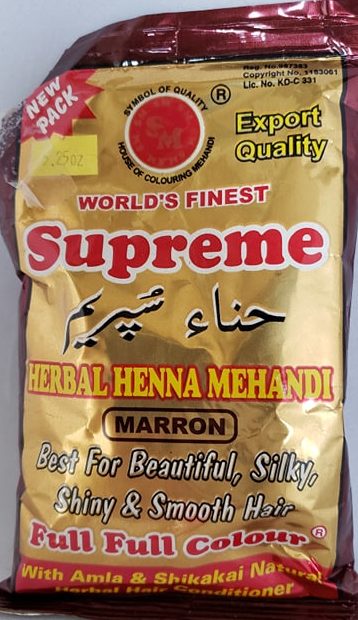

This final product is made in India. I can be bought online as well as in ethnic stores. “Marron” is another word for brown. The ingredients are as follows: “Natural Henna, Aritha, Amla, Shikakai, 2 Nitro, PPD & Other Natural Herbs.” While henna is the first ingredient listed, we can see at the end of the list, “2 Nitro, PPO, & Other Natural Herbs.” It is impossible to know what the other “natural herbs” are.

PPD is clearly listed. 2 Nitro is also known as 2-Nitro-P-phenylenediamine. It is a derivative of PPD. Aritha is also known as soapnut, which is used for cleaning. It contains natural saponins. It does not dye hair. Whether or not it is ideal to use a saponin in a henna mix is unknown. The natural soap may or may not affect dye uptake.

It is likely that the majority of the color effect in this product comes from PPD and its derivative. Indigo is not listed as an ingredient, yet the product claims to color hair brown. The instructions recommend mixing the powder with water and letting it sit for 30 minutes before applying, then leaving it in the hair for 2-3 hours. This is a very long time for a product containing PPD. Most box hair colors that contain PPD recommend processing for no more than half an hour.

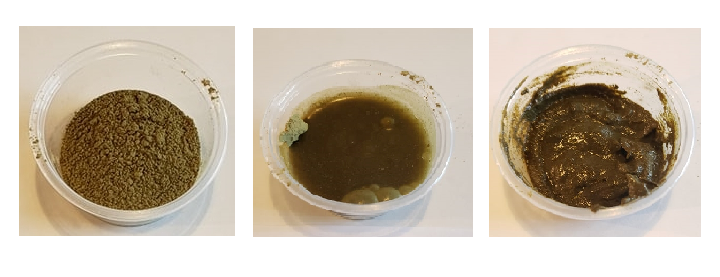

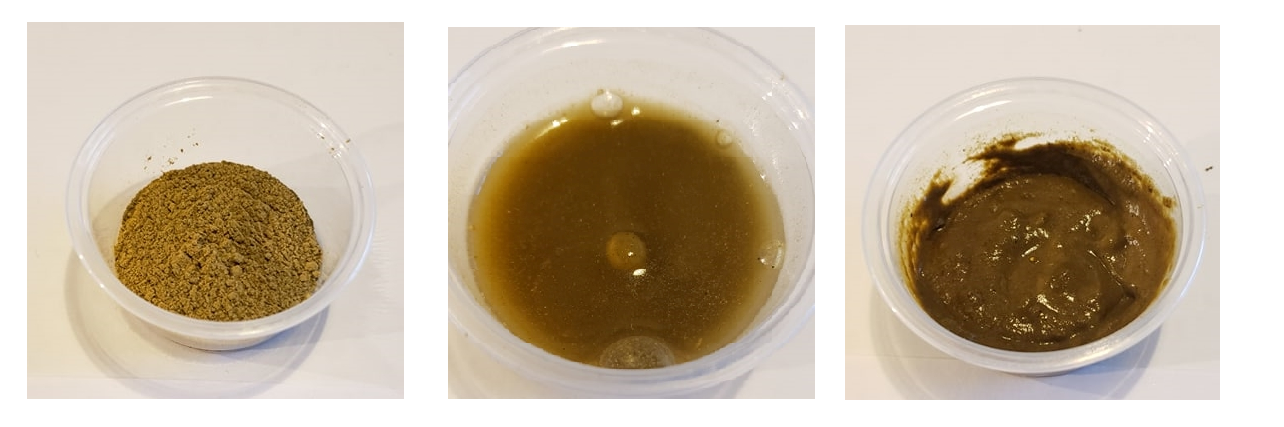

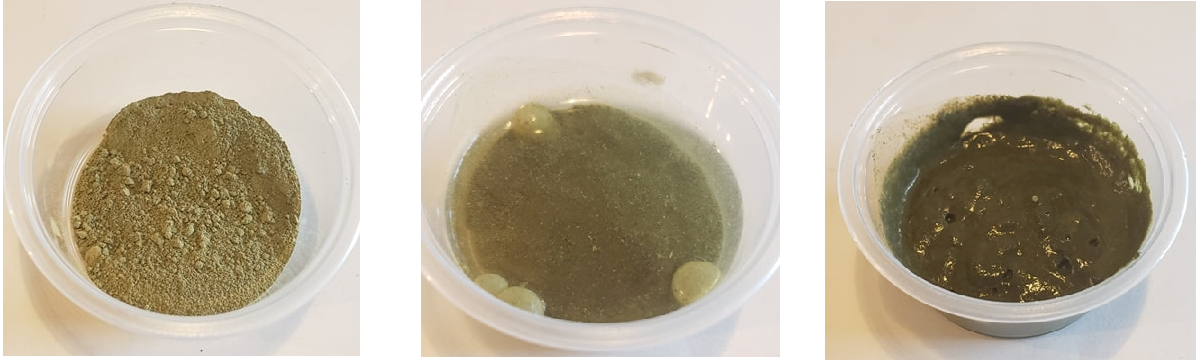

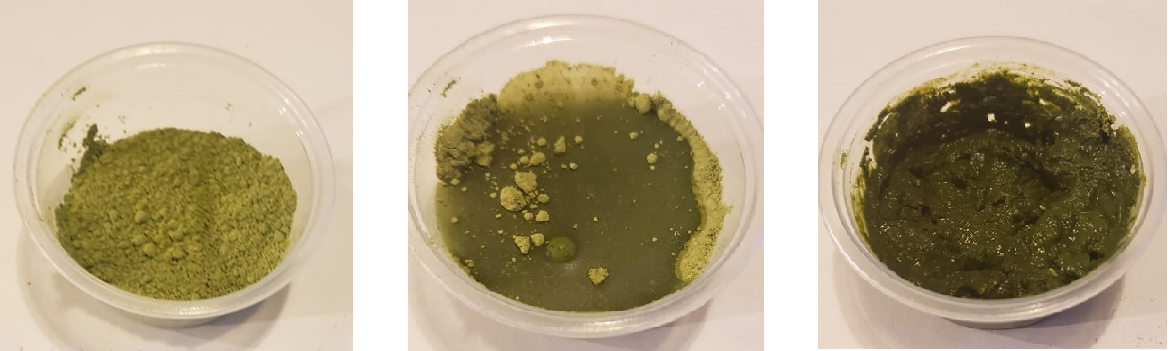

Powder and Paste Qualities

5 grams of each product was measured into respective containers. Color, scent, and texture was noted for each sample. Each sample was mixed with 15 ml of room temperature distilled water. Prior to stirring, one can often see larger plant particulates which rise the surface of the water. Color, scent, and texture of the resulting pastes were noted.

While plant dye powders can vary in color, it is not always indicative of quality or freshness. A common misconception is that fresh henna powder has a bright green color. In some cases, green dye is added to the powder to make the appearance more appealing. Pure henna powder can be pale brownish green to bright green in color. Indigo powder tends to be very bright green. When mixed with water, indigo will turn a deep green-blue. Additional herbal plant powders may affect the color of the powder and paste. What is not ordinary is for powders and pastes to be vivid orange or red, or very dark brown or black.

#1

The powder is a light olive green color. It has an earthy, plant scent without any strong synthetic, floral, or herbal scents. The sift appeared average to the naked eye. When water was added, the liquid turned a dark green color almost instantly. Some larger plant particulates (pieces of leaf, vein, or petiole) floated to the surface of the liquid. After stirring, the resulting paste was dark green, slightly gritty, and had a faint herbal scent.

#2

The color of this powder was a light, yellow-olive color. The scent was plant-like and neutral. The powder included some soft lumps that broke with a light touch. When mixed with water, the resulting paste was a medium green. Some larger plant particulates were visible floating on the surface of the liquid prior to stirring, but not as many as in sample #1.

#3

The powder was chalky sage green. The sift appeared normal to the naked eye. No strong scent was noted, but the classic “frozen peas” scent of indigo could be detected. Upon adding water, the paste turned a medium to deep green color. A fair amount of particulates were floating on the surface of the water. The paste had a stretchy, mucous texture which is common with hennas from certain regions.

#4

This powder was a dusty, light brown color. The scent of amla and other herbs was predominant. A considerable amount of larger plant particulates could be seen both in the powder and floating on the surface of the added water. The paste was a gray-brown color with a lumpy, gritty, and mucous texture.

#5

The powder was a dusty, light brown color, somewhat lighter than that of sample #4. No chunks or large plant particulates were visible. The powder had a notable “herbal henna blend” scent. When mixed with water, the paste frothed. The paste had a faint metallic and chlorine scent along with the herbal scent.

#6

The powder was a bright, light green color. There were not large plant particulates visible in the powder. The classic indigo scent was present. There was no noticeable herbal or synthetic fragrance scent. When water was added, the powder turned a bright green color. After mixing, the paste was thick and dense like wet clay. The paste was a similar color to cooked spinach.

#7

The powder was a green-gray color with some soft lumps that broke apart under light pressure. No discernible scent was noted. The paste frothed when mixed with water. The color of the paste was a chalky sage green.

#8

Immediately upon opening the package, this product had a strange, strong scent that was difficult to describe or identify. The color of the powder was terracotta orange. When water was added, some plant particulates could be seen floating on the surface. The paste was a bright orange-brown and had a thick consistency like icing.

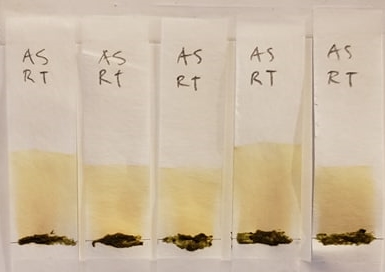

Ancient Sunrise Rajasthani Twilight Henna (ASRT)

This powder had a pale, yellow-green color and scent like dried grass or straw. After adding water, there were very few plant particulates noticeable on the surface. The paste had a mucous-like and lumpy consistency similar to cottage cheese upon first stirring. The paste became smoother and stringy after stirring. The color of the paste was a muddy greenish brown.

Ancient Sunrise Zekhara Indigo (ASZI)

This powder is fine and fluffy with a bright green color like matcha tea powder. It has a distinct scent that is slightly metallic and reminiscent of frozen peas. When mixed with water, the paste is dense and smooth like wet clay. The paste turns a deep, blue-green.

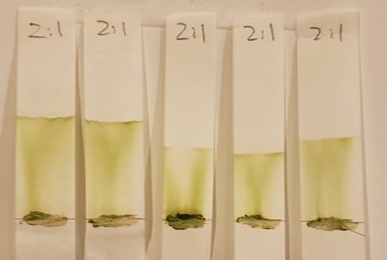

2:1 Ratio of ASZI and ASRT

For the purposes of this article, a mixture of two parts indigo and one part henna was created to mimic a premixed product intended to color hair dark brunette. Normally, henna and indigo pastes are mixed separately before being combined. This resultant powder naturally showed characteristics of both ASRT and ASZI. The color was a lighter green than indigo powder alone, and mixed to a dense and slightly slippery paste.

Chromatography

Paper chromatography is a simple method used to separate dyes and/or to determine the existence of dyes in a substance. A small sample of the substance is placed on a strip of paper which is lowered into a glass chamber where the end of the paper strip wicks a liquid solvent. As the solvent moves up the strip and through the sample, the dye or dyes are pulled up along the paper at varying rates. By comparing chromatography results of different “henna for hair” product samples, one can see speculate on the dyes contained in each sample. Part One of this series discusses the chromatography method in further detail.

Here is a time-lapse video of a paper chromatography test from Part One.

This group of samples was tested under the same conditions as the set from Part One. Samples were tested in

1) A solvent of 99% isopropyl alcohol for 20 minutes,

2) A solvent of equal parts distilled water and 99% alcohol for 15 minutes, and

3) A solvent of equal parts distilled water and 100% acetone for 15 minutes.

It was necessary to test samples under multiple conditions because the target dyes were unknown. As will be seen in the results, some dyes will react differently to each solvent. Unlike the samples in Part One, which were mixed with a leon juice dilution and allowed time for dye release, these samples were mixed with distilled water only. The resulting pastes were applied to the paper strips and tested immediately. This is because a number of the samples in this group contain indigo which releases rapidly and requires a neutral or alkaline environment. In addition, most of the products’ instructions recommended mixing with water only. In order to maintain consistency across samples, room temperature distilled water was used with each sample rather than following individual product mixing instructions.

Results

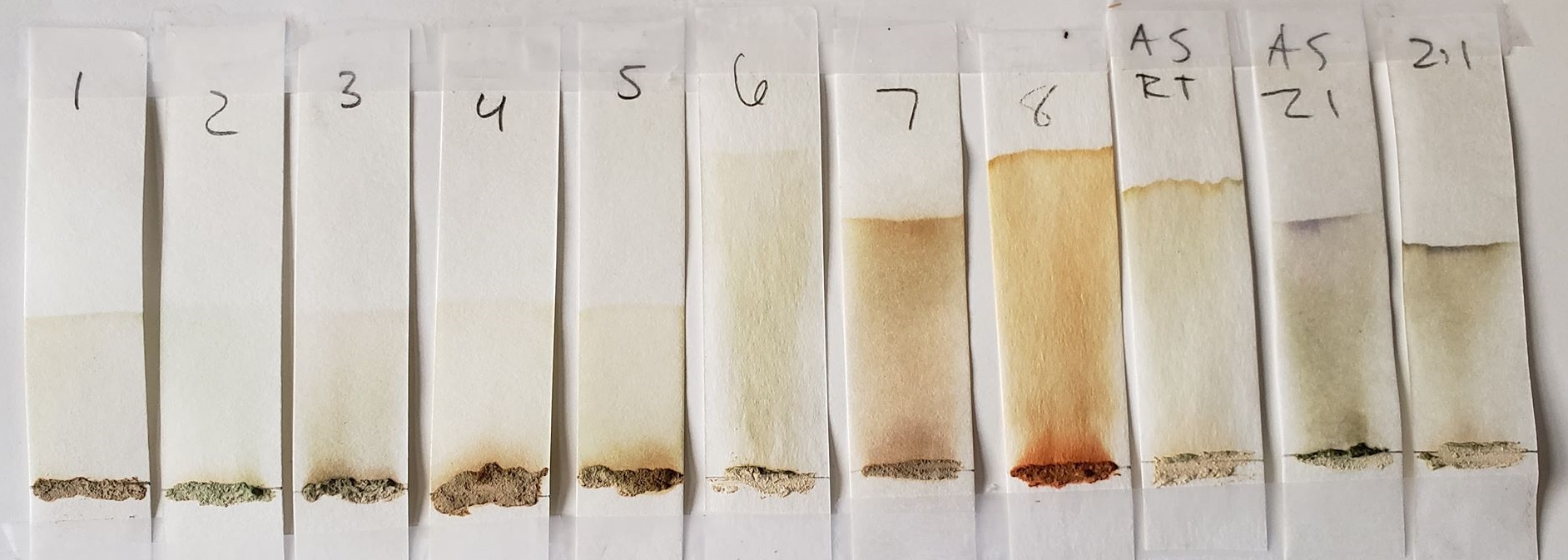

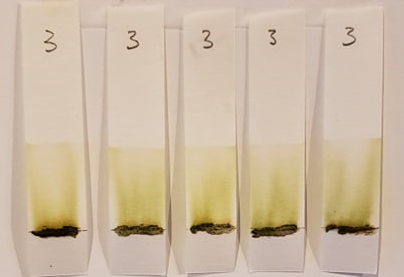

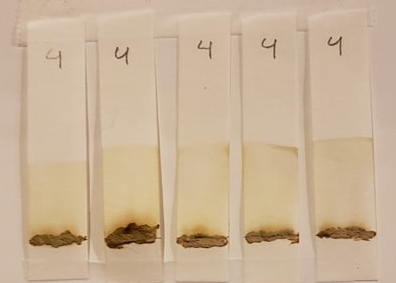

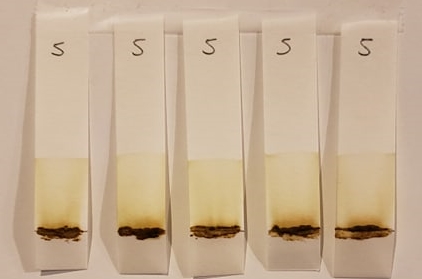

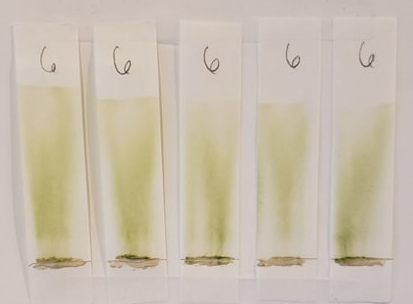

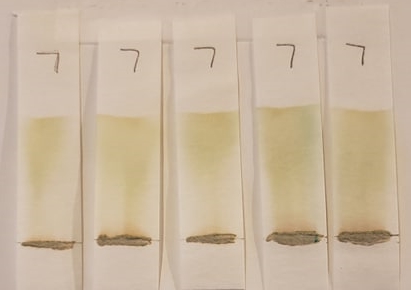

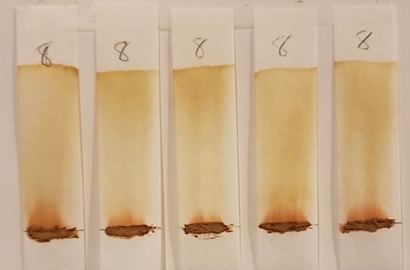

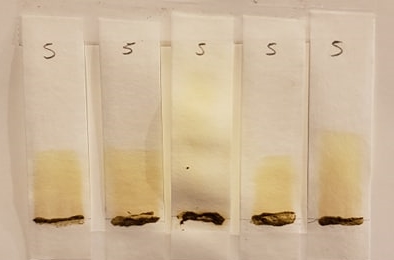

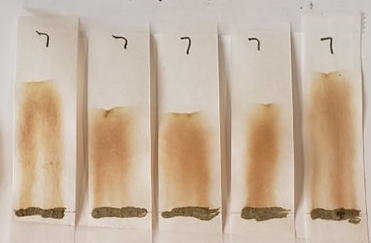

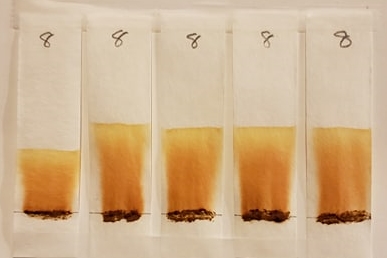

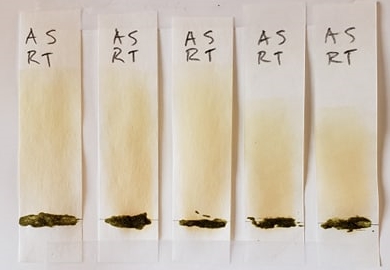

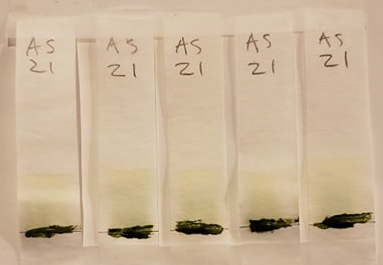

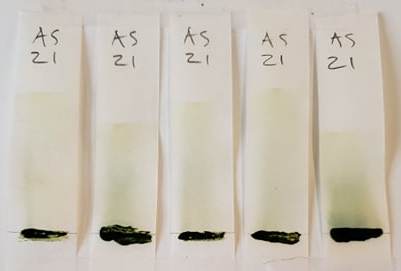

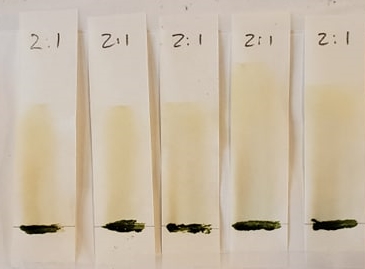

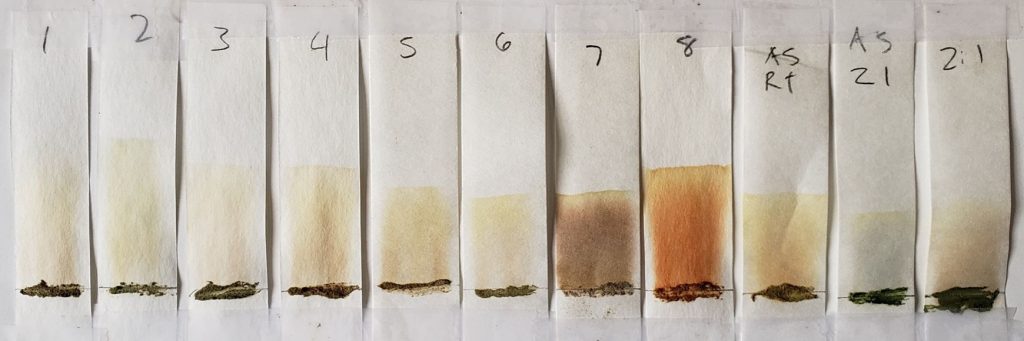

99% Isopropyl Alcohol for 20 Minutes

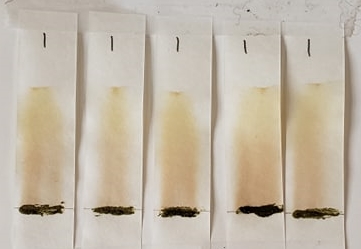

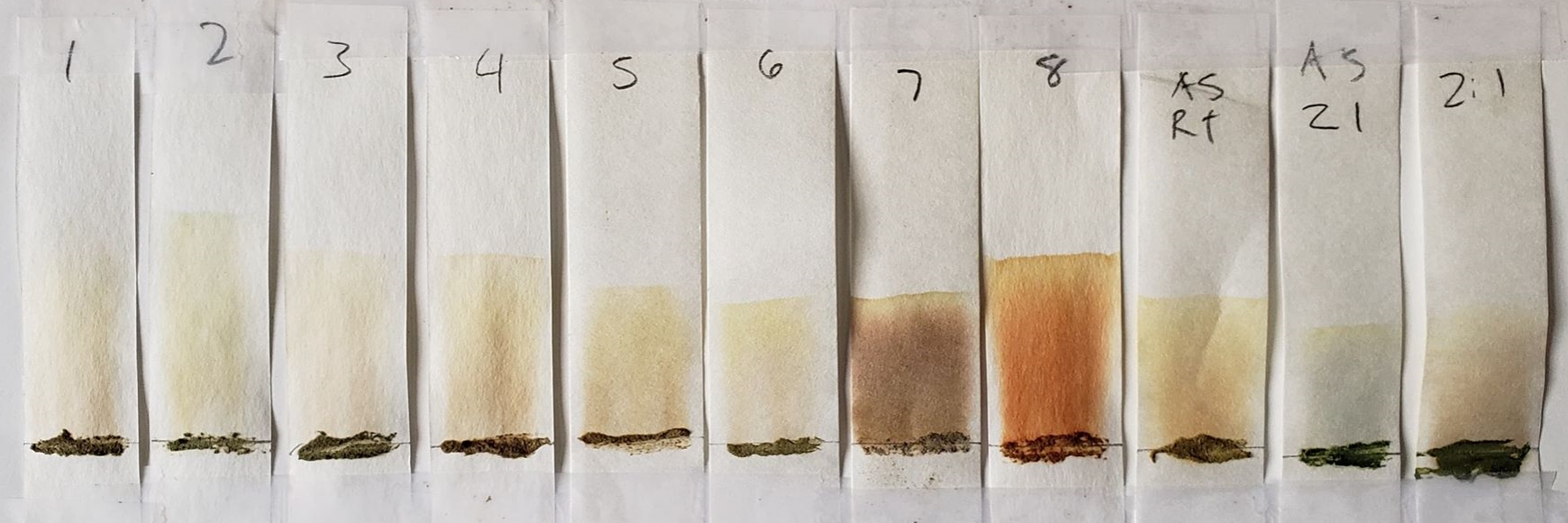

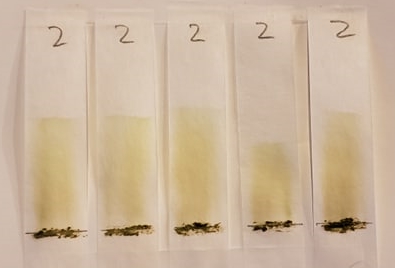

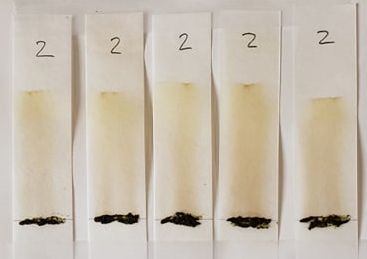

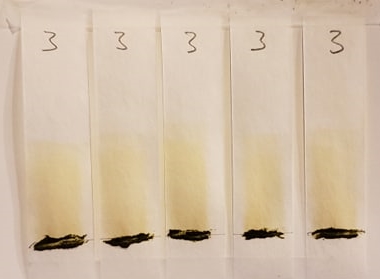

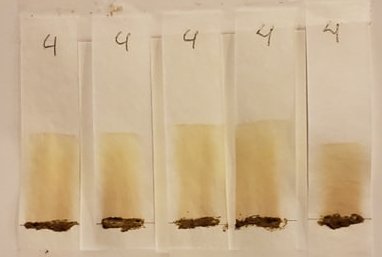

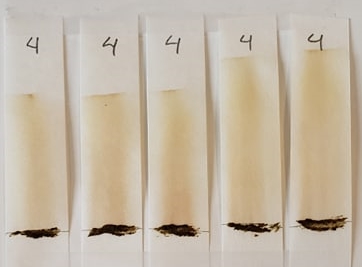

Each sample was tested on five individual paper chromatography strips. Most results were consistent; occasional inconsistent results were disregarded and attributed to variation in paper strip composition or other unforeseeable factors.

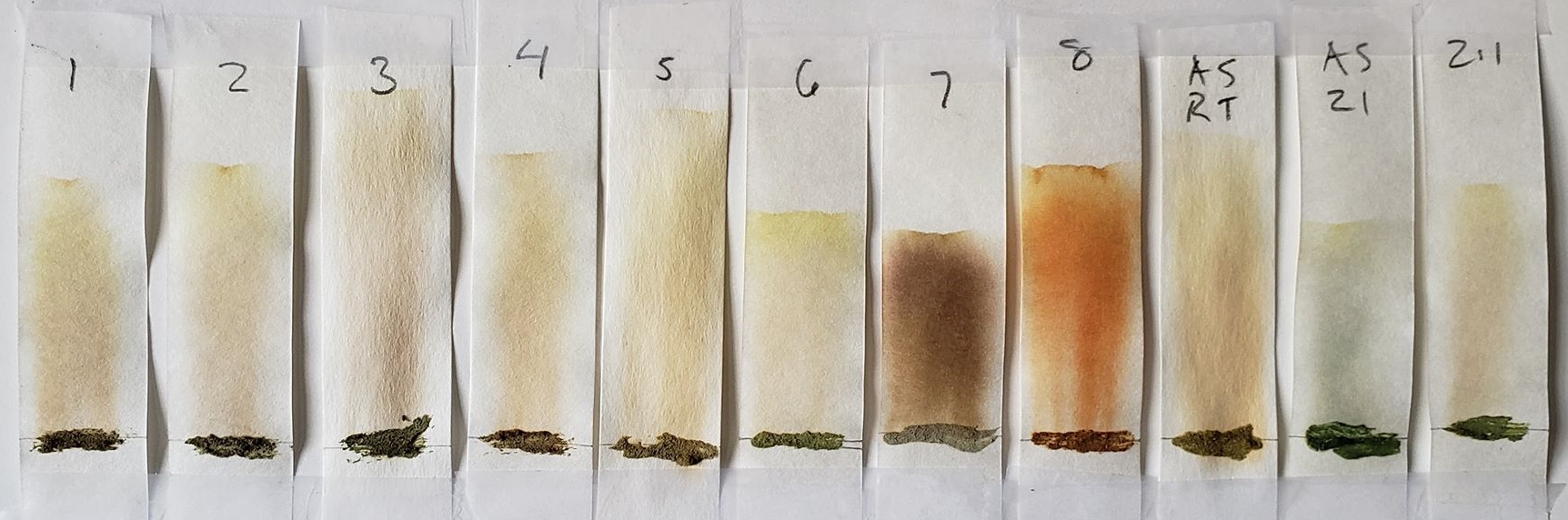

Below is a comparison of all samples including Ancient Sunrise Rajasthani Twilight Henna (ASRT), Ancient Sunrise Zekhara Indigo (ASZI), and a 2:1 ratio of ASZI and ASRT. One strip of each sample was selected to create this image. Note that the solvent front (the highest point reached by the solvent) is consistently lower in samples 1-5. This is due to inconsistency in the paper strip manufacturing rather than a difference in the product samples. However, it cannot be ruled out that the change in paper density may have affected the way we visually interpret the results.

Additionally, this image was taken after all samples had been tested and the paper strips had fully dried for several hours. Some samples lost color while others deepened in color. This will be discussed in the Limitations and Considerations section. Following images will show samples immediately following testing.

99% isopropyl alcohol is a virtually anhydrous solution. In other words, there is very little water. While a very small amount of water exists in the sample paste and in the solvent, it may not be enough to cause oxidation. Therefore, this condition should not reveal much lawsone or indigo dye. We see significant differences in the colors of samples 7, 8, and 2:1.

Sample#1

The result had a very pale, yellow-green tone. While the stain appears mostly even from the point of application to the highest point reached by the solvent (also known as the solvent front), the deeper part of the stain appears to end about two thirds of the way up. This sample reported henna, indigo, centaurea, and beetroot as its ingredients.

Sample#2

Sample #2 had results which were paler in color. This was an herbal blend which contained henna along with many other herbs which may or may not have dyes. While Sample #1 contained some amount of indigo, this sample does not.

The result also showed some very slight green-blue vertical stripes which may suggest that dye was added to affect the color of the powder. This was seen in a sample in Part One of this series. Because it has been believed that a green henna powder indicates freshness, some manufacturers add dye to change the powder’s appearance. It is possible that this is what happened here. Part One discusses the practice in more detail.

Sample #3

The result was a yellow-green tone similar to the result for sample #1. Like #1, this sample also reported indigo in its ingredient list. The dyes involved in this sample did not move with the solvent as much as the previous two; much of the coloration remained lower near the point of application rather than rising all the way to the solvent front.

Sample #4

This sample’s results was closer to that of Sample #2. Sample#4 and #2 are both herbal blends which do not list indigo in the ingredients. Thus, the result is very pale because whatever henna may be included in the mix is diluted with herbal ingredients which contain no dye. However, this sample shows some dark red-brown banding that appears just above the point of application and does not move further up the strip. This is inconsistent with henna’s lawsone dye. It is unclear what may cause such results.

Sample #5

This was another henna/avurvedic herbal blend which did not include indigo in the ingredients list. Similar to Sample #4, the result was mostly pale with some darker red-brown banding just above the point of application.

Sample #6

It should be noted that while the solvent front for this sample is much higher than the previous five samples, this is most likely due to a change in the manufacturing of the paper strip rather than a factor of the sample itself. This sample showed a gray-green color which was darkest about halfway between the point of application and the solvent front. One can see some banding about a centimeter above the point of application. This sample reported indigo as its first ingredient, followed by henna, cassia, and amla. The result is visually similar to the results of samples #1 and #3.

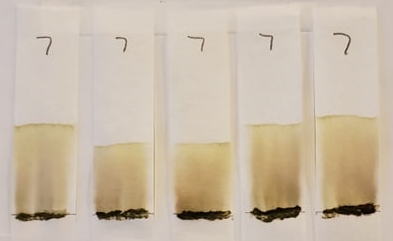

Sample #7

This sample differed from previous samples. There was a light red-brown band just above the point of application as well as some green vertical striping, most noticeable in the paper strip second from the right. As the sample dried and oxidized, the overall color deepened further and the green tone was overtaken. This effect was unlike that of most other samples which darkened very little. This product did not include a list of ingredients. The green coloration is very likely due to the same kind cause as in sample #2: an added synthetic dye rather than indigo.

Sample #8

This sample showed results unlike any of the previous seven samples. The overall stain was deep orange with a very noticeable red-brown band above the point of application. While the product reported two forms of PPD in addition to henna and some ayurvedic herbs, this does not explain the vivid orange color. There is very likely another dye or number of other dyes which were not listed.

ASRT

The Ancient Sunrise Rajasthani Twilight henna sample showed a pale stain that was similar to samples #1-6 but had a warmer orange tone. This would make sense as this is a pure henna whereas the other samples in this collection are blends of henna and other plant powders.

ASZI

This sample was pure Ancient Sunrise Zekhara Indigo. The result was a deep olive green color with some hints of banding about halfway between then application point and the solvent front. As the sample dried, the color oxidized to a pale, gray blue.

2:1 ASZI/ASRT

This sample was a blend of two parts Ancient Sunrise Zekhara Indigo and one part Ancient Sunrise Rajasthani Twilight henna. This mix is what is recommended for dark brunette results. The color was much like the results for pure indigo powder, but with a slightly warmer tone due to the addition of henna. When the paper strips dried, the color oxidized to a cooler brown tone.

Of the eight samples, sample #6 came closest in appearance to the 2:1 indigo/henna mix. Sample #6 reports indigo as its first ingredient, followed by cassia auriculata, henna, and amla.

Sample #3 also reports indigo as its first ingredient, then followed by henna, amla, and a number of herbs that do not dye. The results from sample #3 also have a similar, gray-green tone, but much lighter. It is likely that the strength of the plant dyes was diluted with the addition of other plan powders.

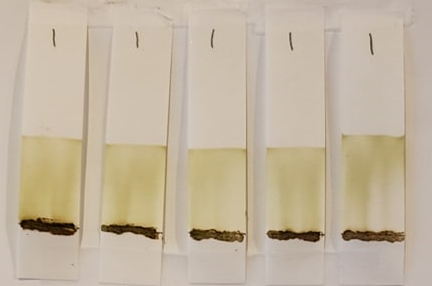

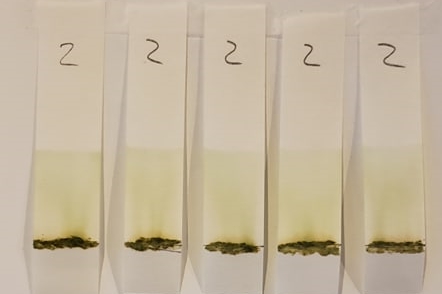

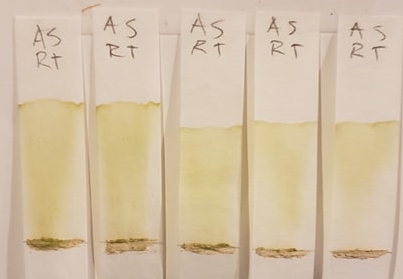

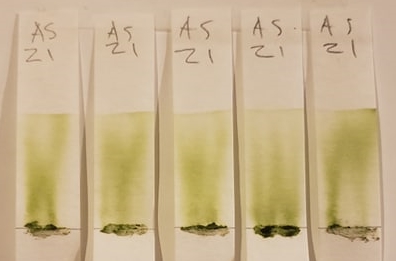

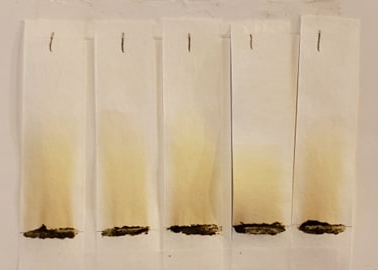

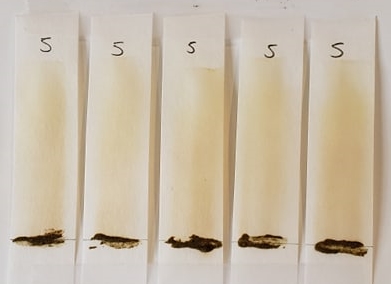

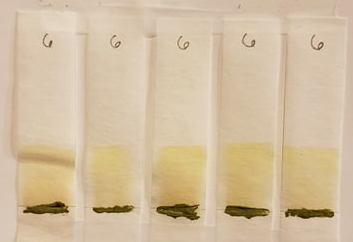

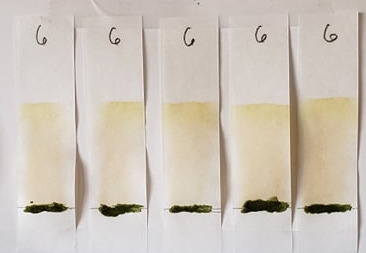

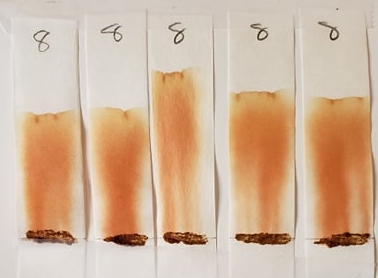

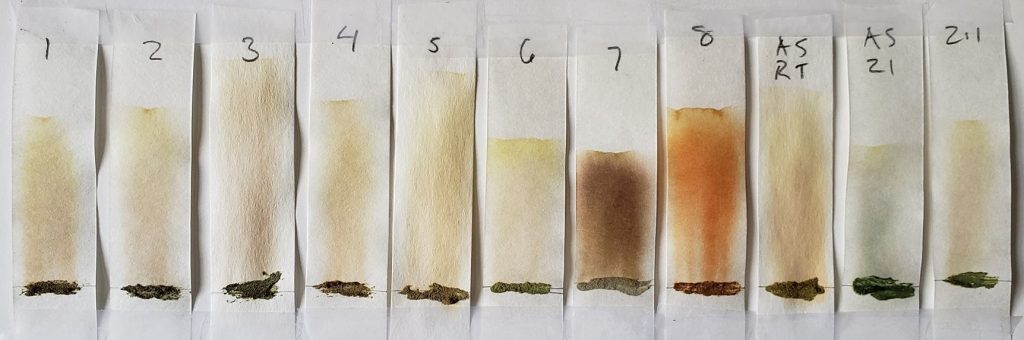

1:1 Dilutions for 15 Minutes

The results from an anhydrous solvent such as isopropyl alcohol will differ from that of a solvent containing water. In prior tests, using pure acetone as a solvent yielded results that were not useful; therefore, pure acetone was not used as a solvent condition in this series at all. In the case of the lawsone and indigo dye molecules, they require at least some water in order to oxidize. While the samples in the 99% isopropyl alcohol condition above were mixed with a few milliliters of water, it was not quite enough to allow the colors of the dye molecules to show.

This section reports results of the using A) a 1:1 mixture of isopropyl alcohol and distilled water and B) a 1:1 mixture of acetone and distilled water. Overall, the stains on the samples were much more visible. Results from both conditions were relatively similar to one another. Samples #7 and #8 were especially unique.

Below are results for both conditions. The top image shows the results for the 1:1 alcohol/water solvent condition. The bottom image shows results for the 1:1 acetone/water solvent condition.

Sample #1

Results from this sample were a pale orange tone which was darkest below the halfway point between the point of application and the solvent front, suggesting a wide dye band. As the paper strip dried, the color appeared lighter. The acetone/water solvent condition yielded a darker result and seemed to show a muted, red-brown section from the point of application to roughly halfway up, and a lighter orange tone closer to the solvent front.

Sample #2

Sample #2 appeared very similar to sample #1 but lighter in color. In the 1:1 alcohol/water solvent condition, the stain more even from the point of application to the solvent front. In the 1:1 acetone/water condition, a similar red-brown tone is visible from the point of application to about 2/3rds of the way up. While there was a light green streak in the results for the 99% isopropyl alcohol condition, a green tinge can be seen in the 1:1 alcohol/water condition. The green dye moved all the way up to the solvent front, where it created a thin line. The green tone was no longer visible under the 1:1 acetone/water condition. This suggests that whatever caused the green color is a dye that interacts differently with acetone and alcohol.

A faint green line is perceptible at the very edge of the solvent front in sample #2.

Sample #3

Sample #3 was, like in the first condition, very similar to samples #1 and 2. No distinct banding is noticeable, but the stain gradually fades as it approaches the solvent front. In the 1:1 acetone/water condition, the solvent moved much further up the paper strip. This is most likely due to a variation in the paper itself. As the samples from the 1:1 acetone/water solvent condition dried, the color oxidized moderately and showed a soft brown tone.

Sample #4

Sample #4 was similar to the previous three samples. There is no distinct banding and the color appears relatively even from the point of application to the solvent front, but fades somewhat as it approaches the solvent front. There is a muted red-brown tone from the point of application to about halfway up to the solvent front. Above the halfway point, the color is lighter and brighter. The color of the results deepened slightly after the paper strip dried.

Sample #5

The paper strip in the center of the 1:1 alcohol/water solvent should be disregarded as an inconsistent result most likely caused by a variation in the paper strip. In the 1:1 acetone/water solvent condition, the height of the solvent fronts matched. Sample #5 showed an even, light orange stain and no distinct banding.

Sample #6

This sample was very similar to samples #1-3. The result was pale and even with no distinct banding. On some strips in the 1:1 alcohol/water condition, the color appears darker neat the point of application and gradually fades toward the solvent front. In the 1:1 acetone/water condition, the color appears to be more concentrated near the solvent front in a brighter orange band.

Sample #7

The darker color is much more prominent in this condition in comparison to the result from using 99% isopropyl alcohol solvent. As the paper strip dried, the color oxidized further. This sample did not include an ingredients list in its packaging. The deep, almost purple-gray tone suggests that this sample may contain PPD. A previous test of black hair dye containing PPD yielded results which had a similar color, but much darker.

Sample #8

The bright orange color detected in the first condition is even more prominent in this second condition. While pure henna can color hair and skin a deep orange color similar to this, it is clear that this vivid orange tone is cause by some other type of dye. The lawsone dye molecule requires a slow and steady dye release period in an acidic environment. Given the right conditions, a good lawsone stain will oxidize to a deep orange to reddish-brown on light hair. This product, on the other hand, was tested immediately after being mixed with distilled water. It yielded a vivid orange result immediately.

ASRT

Both conditions resulted in a light, orange tone which slightly after the paper strips dried. In comparison to the 99% isopropyl alcohol condition, the dye is more visible. This is likely because the lawsone dye molecule was unable to release and oxidize as well in an anyhydrous condition; in other words, some amount of water is necessary for lawsone to create a visible stain.

ASZI

While the initial result of the 1:1 alcohol/water solvent condition was paler, some potential banding can be seen in the 1:1 acetone/water condition. The result shows some muted blue-green tone upon removal. After the paper strips dried and oxidized, the color of the results in both conditions deepened to a blue-violet tone. This is in line with the normal oxidation process of the indigo molecule.

2:1 ASZI/ASRT

In both conditions, the results of the 2:1 mixture of ASZI and ASRT appeared initially pale orange in tone. This is likely because the lawsone dye from the henna was more visually prominent at first. However, as the paper strips dried and the dyes oxidized, more of the cool tones from the indigo molecule emerged, turning the overall color a muted brown tone. Based on this result, one would expect that other samples which include more indigo than henna should show a similar result. However, with the exception of samples #7 and 8, the products tested in this article all yielded pale orange brown results that look more similar to the ASRT sample than the 2:1 mixture.

Discussion

Samples # 1, 3, and 6 reported indigo in their ingredients disclosures. One would expect for the chromatography results to appear similar to that of the 2:1 mixture of Ancient Sunrise Zekhara Indigo and Ancient Sunrise Rajasthani Twilight henna, and different from the sample of Ancient Sunrise Rajasthani Henna alone.

In the 1:1 solvent/water dilution conditions, the sample of Ancient Sunrise Zekhara Indigo alone yielded results which were green at first, and which oxidized to a pale violet tone. This tone deepened the result of the 2:1 mixture. This is especially noticeable in the 1:1 alcohol/water condition. After drying, the result was a light, cool brown. One would expect to see a similar tone in samples #1, 3, and 6. Samples #1 and 3 show some slightly cooler tones in comparison to the ARST sample and other samples which did not include indigo. Sample #6 did produce a greenish color in the 99% isopropyl alcohol condition. After the paper strip dried, that color oxidized to a cooler brown tone that was more prominent that the previous five samples of the same condition. In the 1:1 acetone/water condition, the result of sample #6 was much lighter, with a golden band appearing just below the solvent front.

Assuming that the product tested did include henna and (in the case of #1, 3, and 6) indigo, it is likely that the addition of other plant powders diluted the appearance of the lawsone and indigo dyes. The quality of the plant dye powders could have also affected the results.

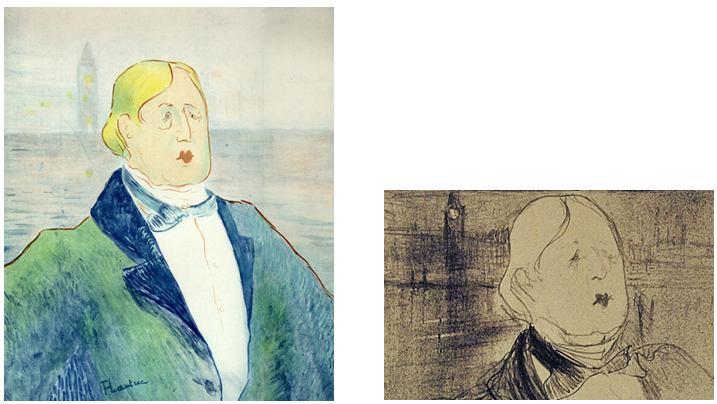

The most salient results came from samples #7 and 8. Sample #7 did not include any ingredients disclosure on its packaging whatsoever. Nor was any information about ingredients available online. The fact that Sample #7 provided extremely small packets of powder, each of which is meant as one application, suggests a high likelihood of the product containing oxidative dyes. The product is reminiscent of many small, concentrated powdered hair dyes which contain PPD which are sometimes used to create “black henna.” These powders have little to no scent. A true henna product requires at least 100 grams of powder to color collar-length hair of average thickness. It is meant to be made into a thick paste, rather than a thin, paint-like liquid.

This is an example of a powdered PPD-based hair dye. Very little powder is necessary for a complete application because the dye is concentrated.

Sample #8 reported PPD and 2 Nitro, a derivative of PPD, on its ingredients list. However, the results of the chromatography tests yielded deep orange results. PPD alone results in a deep, violet-black stain depending on the concentration. This product appears to have a lower concentration of PPD (this does not mean it is safe!) and another dye which is not reported. The ingredients list includes the phrase “other natural herbs.” It is possible that one of the “other natural herbs” is responsible for the orange color. However, it is more likely that the product includes a synthetic dye, possibly an azo dye or a concentrate food coloring, to bring about this result.

Sample #2 showed some faint, green-blue vertical streaks in the 99% alcohol condition. In the 1:1 alcohol/water condition, the same color can be seen at the solvent front. This result different from the blue-green tones of indigo. Unlike indigo, it did not oxidize to a deeper blue-violet tone over time. Additionally, the dye appeared in streaks rather than as a consistent stain. Sample #2 did not report indigo in its ingredients list. It is likely that this sample included a synthetic dye meant to alter the color of the powder itself. A similar effect appeared in Part One of this series.

In all, samples #1-6 showed visually similar results with some variation. They were visually comparable to the ASRT sample and 2:1 ARZI/ASRT samples. Sample #2 showed some blue-green streaks which suggest an added synthetic dye. Sample #7 yielded a very dark brown result which suggests the presence of PPD. Sample #8 yielded a vivid orange result which is very likely due to an added synthetic dye.

Limitations and Considerations

The purpose of this article was to compare a number of products labeled and sold as “henna for hair” products which claim to color hair brunette or brown. It is important to note that the results of the paper chromatography tests are in no way meant to indicate the color result of using any of these products on hair. Paper and hair do not dye the same way, nor was the purpose of this article to demonstrate hair color results.

The hope was that the results of the paper chromatography tests would show distinct color bands which could be compared to Ancient Sunrise henna and indigo results to determine the presence of lawsone and indigo dyes. However, very few results showed distinct dye bands. Future tests should consider new solvent conditions which may show clearer results. Tests using more advanced chromatography methods would be able to separate and identify dyes more successfully.

As noted earlier, the paper strips used for the chromatography tests varied in density. This caused the solvent to move more quickly and higher up the strip in some tests, and more slowly in others. This was an unforeseen factor caused by inconsistent manufacturing. Future tests should make sure to use high quality paper strips which are reliably consistent.

The results of the chromatography tests changed in color as the paper strips dried and as the dyes oxidized. Some dyes oxidized more than others while some colors faded rather than darkened. Because there was no way to test all samples at the exact same time, each paper strip was at a different stage of oxidation when all samples were completed. While photos of each sample was taken just after removal from the processing tank, variation in lighting and camera settings made it difficult to visually compare results. Future studies should take into consideration camera and lighting control.

The final step in this exploration of premixed “henna for hair” products would be to investigate a number of products marketed for coloring hair black. No doubt many products labeled as henna in this category will contain PPD. In some cases, “black henna” sold for both hair and skin is simply a highly concentrated PPD product with little to no henna content. Future investigations should follow the same or similar procedures as Part One and Two of this series to investigate such “black henna” products.