When it comes to henna for hair, the simplest mix is the best. Having a basic understanding, the bare essentials, of the nature of henna and other plant dye powders will lead to beautiful results. Henna is different from boxed dye, so some nervousness or confusion is normal. The internet is filled with conflicting information which makes henna seem more complicated than it is. Ancient Sunrise is built upon decades of research with the goal of providing knowledge and high quality product to the public. The purpose of this article and others in the Henna for Hair 101 series is to educate new henna users so they will feel confident in their knowledge, and excited to begin.

The Beginning

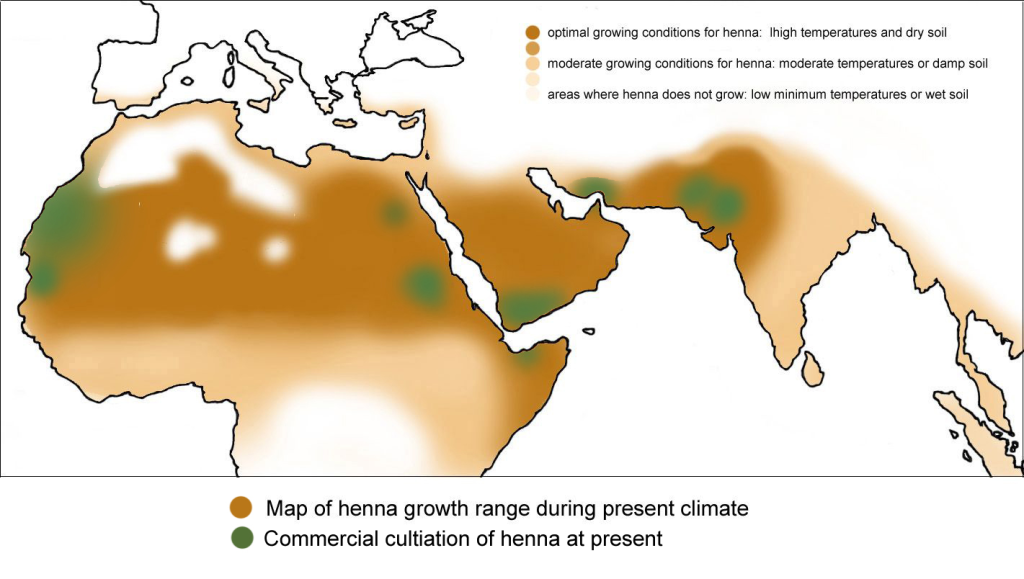

Henna has been used for centuries across the world, in the Middle East, Northern Africa, and South Asia, where the lawsonia inermis plant grows in hot, arid climates. Henna as a hair dye has grown in popularity as many choose to move away from conventional hair dyes. And for good reason. PPD (para-phenylenediamine) and related chemicals are common ingredients in the majority of commercial hair dyes, and can cause serious reactions which will worsen with each exposure. 100% pure BAQ henna is an effective and permanent way to get a beautiful hair color that strengthens and conditions the hair rather than damaging it. Pure henna is safe to use. Adverse reactions are extremely rare.

Background

Henna has been used for since at least 3000 BCE to mask graying hair. In the Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula, Africa, and South Asia, the lawsonia inermis plant grows naturally in hot, semi-arid climates, and everywhere it grows, people have found uses for henna. Henna was used in ancient Rome, medieval Spain, and the Ottoman Empire as hair dye. It was introduced to Europe (where the climate is too cool for the plant to grow) during the 19th century through trade between England, France, and their North African colonies, then during the 20th century into the USA.

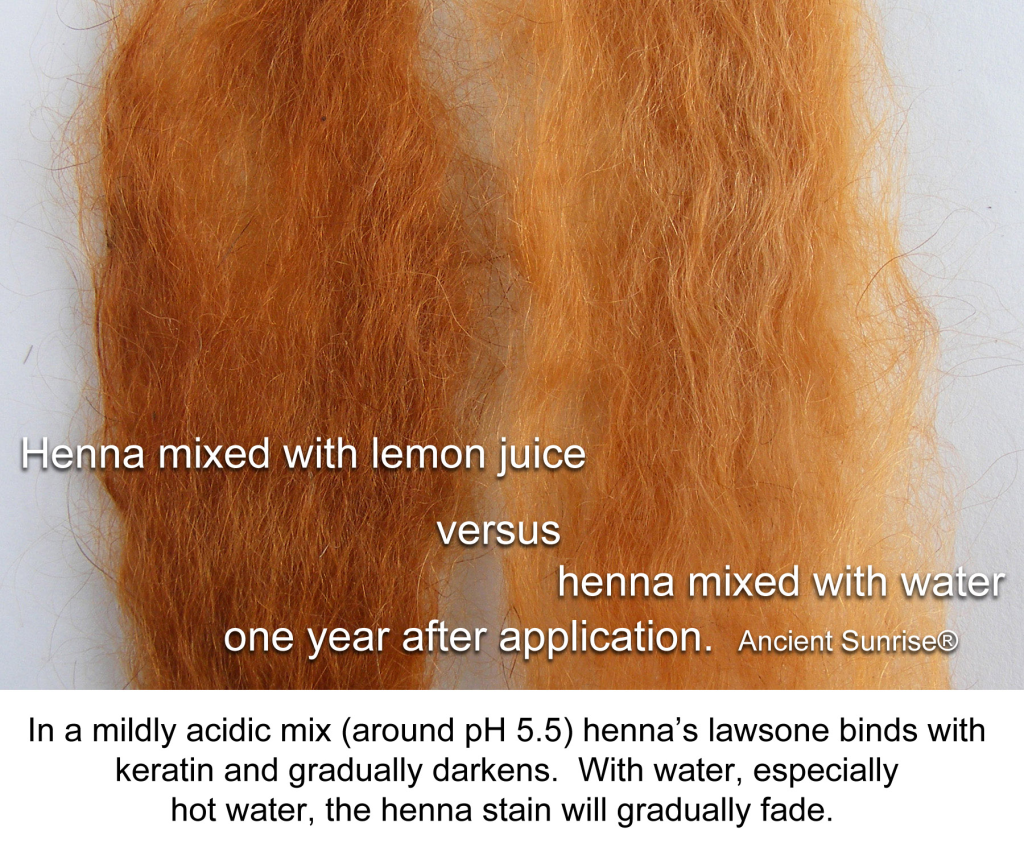

Techniques and recipes to henna hair are remarkably consistent over centuries and continents: henna, with a mildly acidic mix, and time. Many of these mixes are household mixes passed from mother to daughter; most are sufficient, but not as effective as they could be. Understanding the science of henna will help refine mixes without going astray.

During the 20th century, henna suppliers sold compound hennas to Western women who were unfamiliar with henna and who lacked the family-based understanding of henna. Suppliers added metallic salts and chemical dyes to henna in an attempt to simplify the process for Western use. These ‘convenient and modern additives’ only produced an inferior product that doesn’t work right.

Another pattern of henna gone astray comes from a growing interest in home health remedies. As people develop subclinical allergies to the chemicals in common cosmetic and house through constant exposure, they assume that avoiding manufactured chemicals and replacing them with ‘natural’ products will alleviate their symptoms. This is a logical connection, though there are as many allergens in the ‘natural’ world as there in the’ manufactured’ world. Since cosmetics contain oxidative dyes, detergents, and aromatic amines, all of which can be highly sensitizing, more and more people try mixing up something ‘natural’ out of the kitchen.

There are a myriad of blogs which cater to itchy and frustrated people hoping to find relief with homemade hair skin remedies. These ingredients— plant oils, coconut milk, egg, essential oils, coffee, and so on— find their way into henna mixes. Sadly, these rarely have any basis in solid science, are unnecessary, and are often counterproductive to a successful henna dye. You can read Henna For Hair 101: Don’t Put Food on Your Head to learn why.

Keep it Simple

The best results come from sticking to a pure and simple mix made up of two main components: The plant dye powders, and the acids. Once you understand the basics of the henna mix, you can expand your knowledge and tweak your recipe to get your ideal results.

The Plant Dye Powders

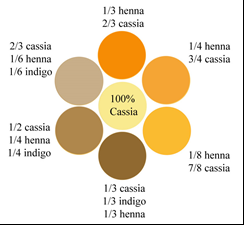

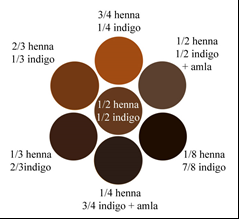

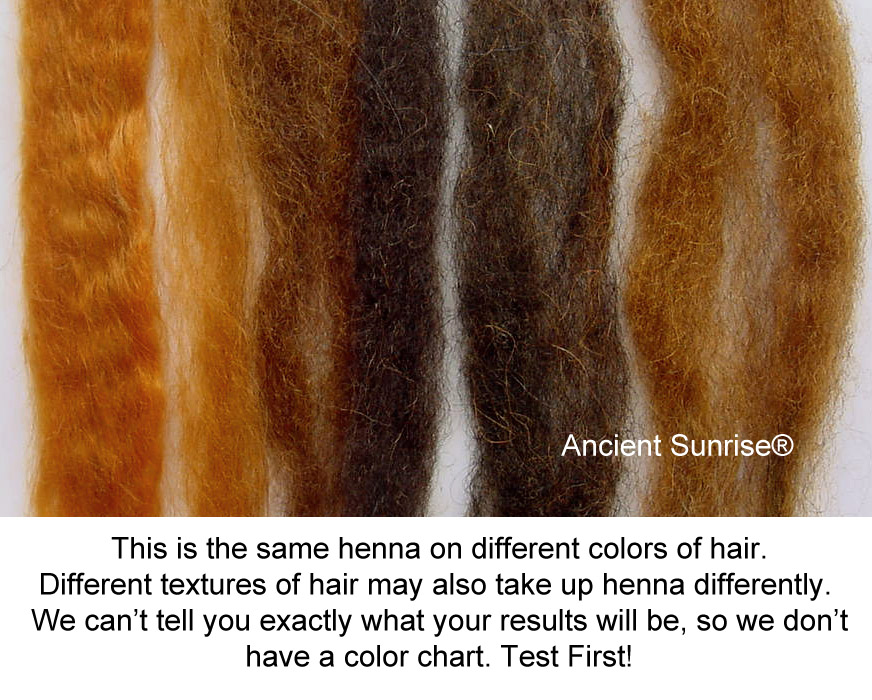

The bare essentials contain three plant powders—henna, cassia, and indigo—a person could achieve any natural hair color, from blonde to jet black. The final color depends on the ratio of these powders, and the choice of acid. While every mix contains henna, whether or not you need cassia and indigo will depend on the goal. All of these powders deposit color onto the hair, and cannot lift color out or lighten what is already there. In other words, if you have black hair, you will not be able to achieve a bright red result unless you lighten first.

After reading this article, be sure to check out Henna for Hair 101: Choosing Your Mix to learn how to decide exactly what you need to get the color you want.

Henna (Lawsonia Inermis)

Henna is probably one of the most important features of the bare essentials. The henna crop is grown in hot, arid climates and produces a natural red-orange dye called lawsone.

The henna leaf contains lawsone, an orange-red dye molecule. This is the base for most plant dye mixes. On its own, it will dye light hair to rich red and auburn tones. Henna powder must be mixed with a mildly acidic liquid, such as a fruit juice, or an acid powder plus distilled water. Leave this paste to sit at room temperature for 8-12 hours for the plant leaf to release the precursor molecule which will dye hair.

Cassia (Obovata(

Cassia’s light, golden-yellow dye brightens lighter hair, and adds golden tones to henna and henna/indigo mixes.

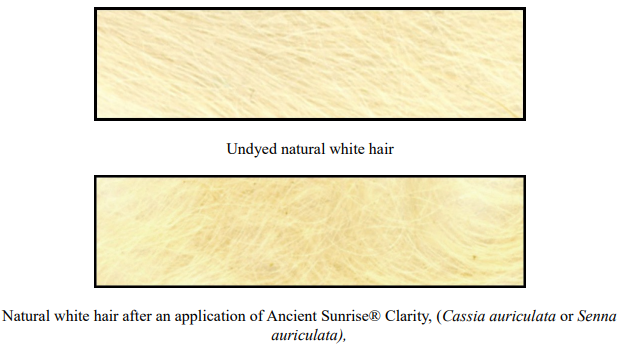

Cassia obovata contains a light golden-yellow dye molecule. On its own, it can brighten blondes, and give grays a light golden blonde tint. Cassia will not change the color of darker hair. It cannot turn dark hair blonde. It is also mixed with henna and henna/indigo mixes to create less saturated reds and brunettes. Like henna, cassia must go through a dye release with an acidic component.

This plant powder can also be mixed with distilled water and applied immediately to condition the hair. For better conditioning results, dye release the cassia first.

Cassia (Auriculata)

Cassia auriculata is a desert plant, though similar to Cassia obovata, is a separate crop. This particular plant powder does not stain the hair as well as cassia obovata. Most people will not get any coloring, even on pale hair. It is okay to substitute cassia auriculata in your henna/indigo mixes for cassia obovata.

Cassia auriculata can help enhance natural curls and conditioning the hair.

Indigo (Indigofera Tinctoria)

The indigo powder used for dyeing hair is partially fermented and dried; this is vashma or bashma indigo.

On its own, the dye molecule in indigo oxidizes from yellow to green, then blue. Indigo and henna together achieve brunette colors. When used in a two-step process—dyeing the hair first with just henna, then again with just indigo—the result will be jet black.

Indigo alone will dye light hair to a green shade that will oxidize to blue-green or blue-violet hues before fading. Dyeing with indigo alone is possible. Indigo by itself can make hair a blue color (similar to jeans). While it will not condition hair like henna or cassia, it can improve shine.

Vashma indigo goes under a natural fermentation in an alkaline medium to release the dye before it is dried and powdered. This makes it ready to use. Add distilled water, not an acidic liquid to make the paste, right before use. Indigo paste will begin to lose its dye strength in as little as twenty minutes exposed to the air. It is important to mix the indigo only when it is time to apply the paste.

Before preparing to add indigo into a mix, make sure that the henna/cassia/acid mix has dye-released. When you are ready, mix the indigo powder with distilled water, stir it into the dye-released paste, and apply immediately.

The Acid

Acid powders are an important bare essentials! Powdered acids derived from fruits are a great alternative to using fruit juice. They have a long shelf life, so they are easy to keep on hand. Just mix with distilled water! Find them at www.mehandi.com.

Henna and cassia need an acidic component and given time to dye-release. Fruit juices such as apple, cranberry, and orange do the job perfectly well and are widely available. You can also mix a fruit acid powder into the henna, and then stir in distilled water. Ancient Sunrise® carries a variety of fruit acid powders to suit all hair textures and color needs.

Lemon juice can be harsh and drying, and the result is a color that is initially bright and brassy, which oxidizes to a deeper, darker color over time. Apple cider vinegar has a similar effect. To avoid irritation and an overly acidic mix, dilute these acids with distilled water, or consider using something else.

Fresh apple juice is gentle on the hair and skin, and contains enzymes that accelerate the dye-release process. Henna mixed with apple juice will be ready within 4-6 hours when left at room temperature.

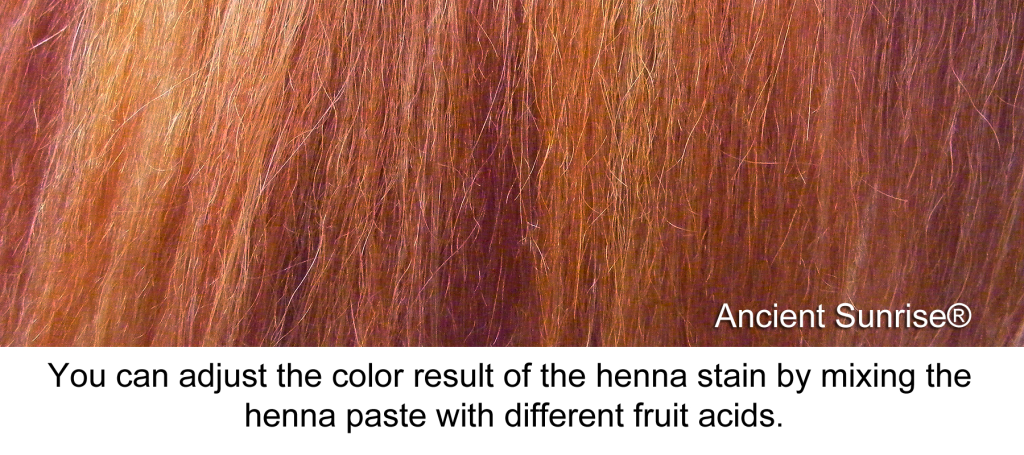

The acidic component may affect the tone of the henna. Some bring out brighter tones, while others add ash tones, or deepen the overall color by a few shades.

Do Not Use:

Wine, coffee, yogurt, egg, oils, coconut milk, or essential oils. These do nothing to help the color. They will make your mix smell and may prevent the dye from binding. In some cases they will cause a headache while the paste is on your head.

Tea might smell nice, but on its own is not acidic enough for dye-release.

Brightly colored plants, such as berries, beets, red cabbage, and hibiscus do not contain dyes that bind to the hair. Adding them in for hopes of a more purplish tone will be pointless.

Putting the Bare Essentials Together

Once you have determined your plant powder ratios, mix your henna and/or cassia together with an acidic component. If you are using an acidic powder, blend all of your dry ingredients first, and then add the distilled water. Pour the liquid in slowly while stirring, until the paste has the thick, smooth texture of creamy mashed potatoes. It should not be runny, but slowly drop off the spoon in a dollop. Cover this with plastic and leave it at room temperature for 8-12 hours.

When dye-release has occurred, the surface of the paste will be darker than the paste underneath, like a bowl of fresh guacamole after a day. You may see orange or red liquid collecting at the top. Dip a finger in the paste, or drop a small amount of the palm of your hand. The skin should show a bright orange stain when washed off after a minute. Note: if your mix is predominantly cassia, these signs may not be noticeable.

If you are not using indigo, you are now ready to apply your henna.

If You Are Mixing Henna and Indigo for Brunette Results:

After your first paste has dye-released, mix the indigo with distilled water only, until it is a similar consistency. Stir the two pastes together well, and apply.

If You are Doing a Two-step Process to Achieve Jet Black Hair:

Apply your henna for the required amount of time, rinse, apply freshly mixed indigo to clean hair within 48 hours. Do not mix the indigo until you are ready to apply it.

For tips on application, click here.

Recap of the Bare Essentials

The basis to a successful mix has only two components: plant dye powders, and the acid. Sticking to a simple mix will ensure the best results. Applying to clean, clarified hair and leaving the paste in for three hours will result in the best coverage. If desired, mixes without indigo can be left on for several hours. After rinsing, the color will take up to a week to oxidize. It starts brighter then deepens down into its final color.

If you are unsure about your mix, it is best to test first. Adjust your mix based on the results after oxidation. If you need help, feel free to contact Customer Service for advice!

For more information, feel free to consult the Ancient Sunrise® Henna for Hair E-book.

Author: Rebecca Chou

Edited: 2022 by Maria Moore

My daughters are henna users Ancientsunrise ..we thankyou for this clear wonderful information*

And we thank you for your continued support!

Sustain the excellent work and producing in the group!