A dive into hair space identities.

Navigate:

- Introduction and Writer’s Note

- Hair and Identity Construction

- Black Barbershops as Cultural Spaces

- Hair and Class

- Hair and Gender

- Client and Stylist Relationships, and Conclusion

- References and Images

Introduction

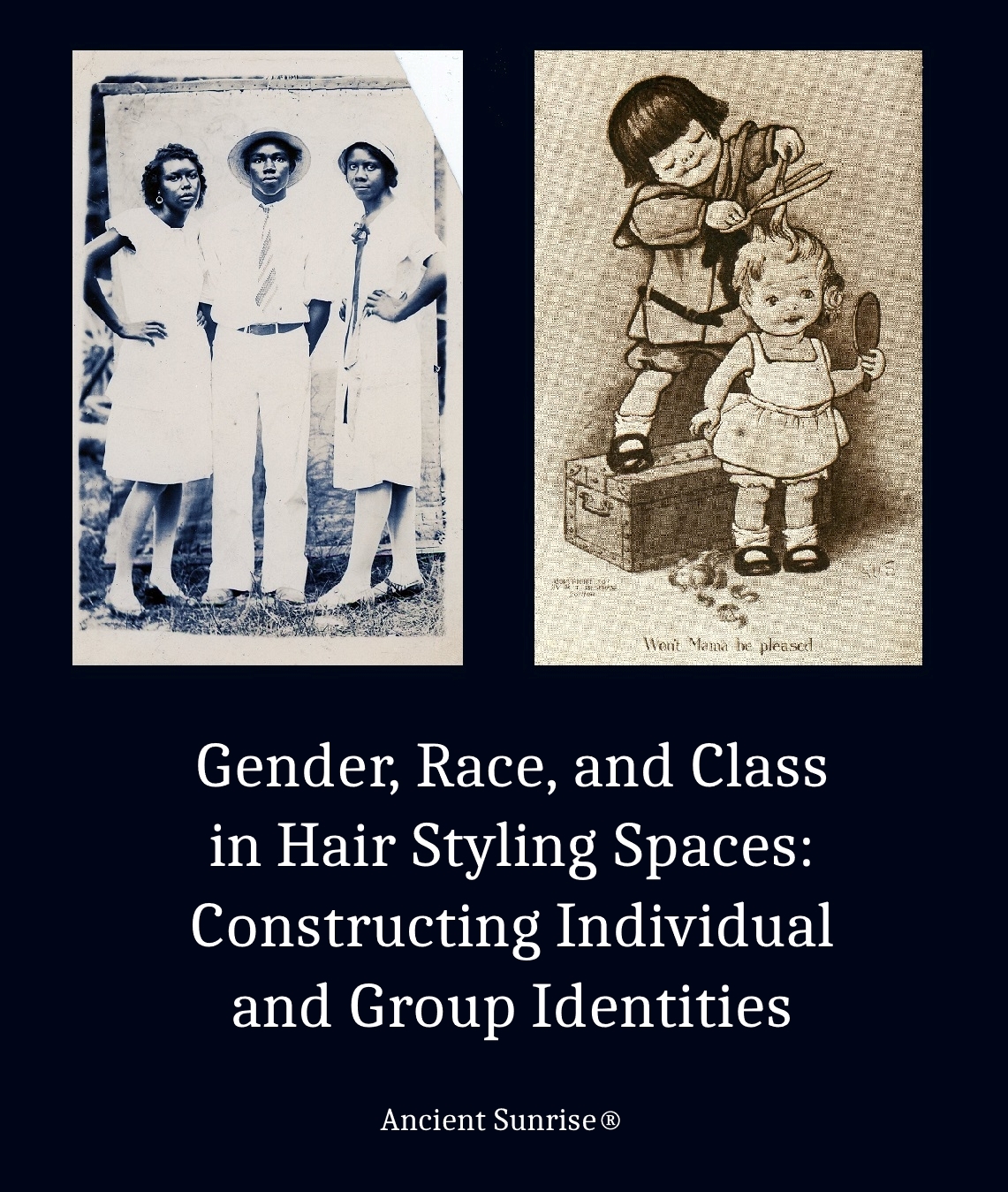

[Image 1]

Hair is complex. As a physical attribute of nearly every human, it is not only an object but an idea: a symbol of the self. As many sociologists note, hair is the most easily manipulated aspect of personal appearance, yet it must always be controlled, or managed in some way [1]-[4]. Hair grows whether or not we want it to. It grays and thins. Its texture and shape defies our wishes. Hair provides information on gender, age, social status, race, and even religion. Anthony Synnott writes, “Hair is perhaps our more powerful symbol of individual and group identity—powerful first because it is physical and therefore extremely personal, and second because, although personal, it is also public rather than private” [1]. When we do our hair, we are saying something about ourselves. Even if we leave it untamed and unwashed, shave it all off, or cover it, we are still signifying our identity and our relationship with society. As Helene M. Lawson notes in “Working on Hair,” “Within each culture styles may be used as symbols of power, signs of rebellion, or to emulate those who have more prestige” [4].

Hair carries the weight of gender, class, and race. Women are told that short hair would make them look “manly” or “lesbian” [5]. The opposite occurs for men who grow their hair long. Many white-collar workers see their hair as an investment in their professional success [6], [7]. African textured hair is especially political, and has a long and complicated history. When a person chooses to wear their hair in a way that falls outside of their social group’s norm, it is often interpreted as rebelling against the ideologies of that group.

[Image 2] Hair carries messages of identity and social group.

Because hair is so intrinsically bound in identity, the act of “doing hair” is ritualized. It is a social act that holds the weight of individual and cultural significance. Hair salons and barbershops become cultural centers, where identity is negotiated and created. The acts of choosing a hairdresser, communicating a desired look, and trusting the skill and physical touch of the hairdresser, create a unique relationship. Beyond the physical act of “doing hair,” hairstylists also function as emotional laborers, taking on the role of confidants, therapists or even role models (For examples, see [8]-[11]). Because each person wishes to look a certain way, be treated a certain way, and be among people with whom they share common interests, a person’s choice of salon or barbershop sheds light on their “desired self.”

This article explores hair salons and barbershops as cultural spaces where identity is communicated, negotiated, affirmed, and shaped. Salons and barbershops have historically been divided sharply along the lines of gender, race, and class. These spaces work to confirm a person’s identity within social constructs. Black barbershops have been well-studied as spaces in which black men engage in cultural exchange, and guide young men [10], [11], [12]. Barbershops as a whole have been almost exclusively masculine places where masculinity is affirmed and femininity is scrutinized [4], [6]. Beauty salons, especially higher-end ones, are predominately feminized spaces, but see a growing number of male clientele. As Kristen Barber noted in “The Well-Coiffed Man,” male clients of hair salons enjoy the pampering and personal attention they receive in hair salons, yet attempt to re-frame their motivations to affirm their masculinity [6]. Men who work as hairdressers in the feminized space of hair salons also have ways to negotiate their masculine identities [13], [14].

Spaces where hair is “done” are full of complex cultural transactions. They are places where ideas about cultural identity are spread, where personal identities are affirmed, and where desired identities are constructed. This article focuses on the relationships within grooming spaces and how clients shape and affirm their identities with the help of their stylists.

[Image 3] Doing hair is a social act.

Writer’s Note

I write this from the perspective of a researcher, studying the works of sociologists, ethnographers, and other academics. I am an Asian-American woman who grew up having her hair cut in the kitchen by her mother, then later at unisex chain salons which focused on efficiency and customer turnover. I’ve been to salons only a handful of times, and preferred to sit quietly while having my hair done. Thus, I did not establish a meaningful relationship with my stylists. The locations I visited catered to a predominately white, suburban population. I have no experience in male barbershop environments. My personal experiences may be a benefit, as I have little bias; I examine these spaces with emotional distance. However, there is always the possibility of unintentionally “othering” or making sweeping generalizations due to my lack of such experience. Therefore, I approach these topics with the awareness that the spaces I plan to write about are both unfamiliar and complex. I rely on the reportage of others, with the trust that their methods are sound and their conclusions justified.

This article is based on my readings of academic works, many of which involve both observation and the authors’ personal reflections. Those who wrote about black barbershops were themselves black men, and detailed their own experiences with barbershops [10], [11]. Other works focused on collections and analyses of interviews, or quantitative data. In these works, stylists and clientele were interviewed and/or observed in spaces that varied in location and demographic.

Any social space is made up of individuals, and the individuals set the tone of the space [10]. Therefore, each salon and barbershop has its own unique qualities. There will be spaces which do not fit the description of those observed in these studies. It is impossible to observe every hair styling space in existence; as with all research, some generalizations are necessary. My goal is to synthesize the ideas made across numerous works to shed light on a larger picture, without confusing generalizations for individual truths.

[Image 4]

Hair and Identity Construction

Hair and Identity Construction

For the sake of ease, I will refer to hair salons, beauty parlors, barbershops, and similar locations as “shops,” and those who work in them as “stylists,” unless it is important to make a distinction between specific types of spaces and workers.

In these shops, clients enlist the skills of stylists to help them achieve a hair style which matches their identity and/or their desired self. This requires communication and negotiation. Because stylists depend financially on a steady stream of clientele, and because clients have the freedom to choose a stylist, it is important that there is a feeling of understanding between the two. Clients often visit the same stylist once they find one that suits them. A client’s choice is influenced by many factors, not limited to the location of the shop, the price of the service, and the physical environment. Most important is the feeling that the shop and the stylist match the client’s idea of him or herself, and the trust that the stylist will effectively create their desired image.

Elements such as the name of the shop, the colors and décor used in the interior, and the images of people and hairstyles displayed, speak to the social identity of those who patron it. Some barbershops described in the studies had deer heads mounted on the walls, sports playing on the TVs, or “dirty magazines” hidden in a drawer [4]. The walls in Black spaces might display images of African American leaders, and styles specific to textured hair [10]. High-end salons choose softer colors and comfortable furniture. Even the reading material in waiting areas vary from space to space.

Emotional aspect of the stylist/client relationship must not be underestimated. Most stylists believe that the level to which their clients feel cared for is just as important, if not more, than the service itself. Stylists believe that making a client feel good about themselves is an important part of their work [6], [9], [10]. They must show they care not only about making the client look their best, but about the client’s personal lives as well. Stylists become confidants and informal therapists. This is not surprising, as grooming is an intensely communal behavior. A bond of trust is formed that allows the stylist to touch a client, work on the client with sharp tools, and talk to the client as if they are friends [6], [8], [9], [11]. Because of this, clients feel comfortable divulging personal information to their stylists. This relationship is more than a transaction of goods or services. A person most likely does not share such intimacy with their mechanic or accountant.

Many sociologists comment on the intimacy that comes with personal touch [6], [8], [9]. Fields such as nursing, physical therapy, and massage show similar patterns in emotional labor. Through touch and talk, the stylist affirms and helps to construct the client’s identity. However, the client and stylist may interpret this talk differently. Some stylists admit that they view emotional labor as simply part of their job. There is an understanding that clients who feel cared for will return, and therefore such behavior is simply necessary for good business. Others find great satisfaction in this aspect of their work, and see working on hair as only a means through which they positively influence others [7], [9], [10].

The feeling of care and community can extend beyond the one-on-one relationship between client and stylist to the space as a whole. When a shop is seen as a place for open cultural exchange, groups of clients and stylists engage in discourse and identity affirmation as part of the expected ritual. For children and young people, these spaces play a role in the enculturation into their social groups [4], [10], [11].

Black Barbershops

Black Barbershops as Cultural Spaces

In the case of Black barbershops and beauty parlors, the role of a grooming space as a communal center is intensified. Barbershops are places where men exchange ideas and information, and pass knowledge to younger men. They have been described as second only to the church as a space for cultural exchange [11], [12]. The act of cutting and styling hair comes second to the act of community, as men use a barbershop as a gathering place whether or not they are receiving services. While topics can range from sports, to history, to goings-on in the community, the discourse serves to strengthen the participants’ identities as members of the community, as men, and as African-Americans.

Black barbershops have a rich history in the civil rights movement and in the growth of the Black community. Hairdressing was one of the first professions available to Black people after emancipation. Initially, Black barbers served exclusively white clientele. While hairdressing was at the time viewed as a servile vocation, it allowed Black men an avenue of entrepreneurship and financial success. As times changed and clientele shifted, Black barbers took on roles of leadership in their communities, and used their revenue to fund community projects [10], [11], [15], [16]. They employed family members and members of the community, and provided a space where people, especially Black men, could gather to discuss important topics.

[Image 5]

The influence of these spaces have been recognized to such a degree that many studies have been conducted on using barbershops and beauty parlors to disseminate information on health issues [10]. Barbers are often respected role-models who see themselves as responsible for teaching and supporting young men. They are “trusted and respected information sources” [10]. The barbers and older clients ask young men how they are doing in school, and what their plans are for the future. They teach them how to talk to each other, and how to show deference to their elders. One client in Shabazz’s study said,

“I learned how to rap in the barbershop because you got to be sharp or they will take your head off, man. The young people don’t have no other spot where can be themselves. Men look out for men and we teach each other what’s real. I used to take my son with me all the time so he could soak up the knowledge. You can’t get that kind of love anywhere else” [10]

In this context, “rap” means to discuss or debate. The client notes that the barbershop teaches young men how to respectfully engage in discourse, and that the space is one in which men can be supported and mentored. Young men feel supported and affirmed in their identities as men and as Black people by learning and engaging in cultural practices. Black barbershops also preserve and teach the history of African Americans. The shop in Shabazz’s study was decorated with African American icons such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Barack Obama. The young men learn about aspects of Black history that aren’t taught in their schools. The Black barbershop is “a site where the cultural and racial familiarity of Back male bodies is acknowledged as meaningful” [11].

The kinds of information exchanged in barbershops vary with the environment. Other studies argue that Black barbershops teach sexism and misogyny when sexist language is used in the presence of young boys [17]. However, this is unlikely to be true of all Black barbershops, nor is it limited to only Black barbershops. As stated earlier, hair styling spaces have been distinctly gendered spaces, regardless of race. In such spaces, there is an idea of “men’s talk” and “women’s talk.” This talk does not necessarily have to be sexist or exclusionary; members of their gender group simply feel at ease being able to openly discuss certain topics without the presence of the other gender. This talk affirms the members’ group identity as men or women. The section on Hair and Gender will explore this further.

[Image 6]

Hair and Class

Hair and Class

Appearance is an important component of middle-class ideals. Those whose work depends on developing personal relationships with partners and clients believe that their appearance is an investment. At the same time, they often express the need for a style that is easy to manage, citing their busy lifestyle. They do not wish for styles that are too outlandish, as their work environments call for appearances that are clean and fashionable, but that do not draw excess attention.

Professional middle-class men interviewed in “The Well-Coiffed Man” expressed the desire for a “stylish” haircut, rather than the “old-fashioned” cuts they equated with barbershops. Equally important is their belief that the female stylists in salons treated them with more care and personal attention, whereas barbershops were places where men talked about “sports and sex” [6]. This suggests that these men felt that their professional, personal, and social identities were better served at salons, despite their perception that they were feminized spaces. Their disdain for the style and environment associated with barbershops suggest that they view barbershops as lower-class. As professionals, they saw their time at the salons as one of the only times they had for themselves, when they could relax, be cared for, and pampered. They also believed that the women who cut and styled their hair were more knowledgeable and skilled. These qualities justified the extra money they spent in comparison to going to a barbershop or unisex chain shop. The men believed that the time and money were necessary investments for their professional relationships, and well-deserved respite from their demanding lives. In contrast, a male client at a barbershop interviewed in Lawson’s “Working on Hair” stated, “I go to a barber to be neat and combed and presentable, not as an asset for attracting women or making money, like yuppies” [4]

[Image 7]

Middle-class professional women tend to prefer simple, “classy” cuts that are easy to manage [7]. They view “big, flashy” hairstyles and unnatural colors as lower-class, and inappropriate for their professional environments.Overall, there is an idea about what kind of hair is “appropriate” for a person’s identity and environment, and deviance from what is appropriate can be interpreted as anything from tacky to dangerous.

Debra Gimlin noted in “Pamela’s Place: Power and Negotiation in the Hair Salon” that there can be class tensions even within a hair styling space, when stylists with lower-class statuses work with higher-class clientele. Stylists wish to see themselves as experts of the beauty world, and want their clients to accept their advice on what they believe is a fashionable or the “right way” to wear hair in accordance to beauty culture. However, the clients’ ideas of appropriateness for their social class may not necessarily match. Stylists must choose to either assert their power as hair professionals, or defer to the desires of their customers. Some reported feeling that they had to sacrifice their professional opinions for the sake of giving the client what they wanted, even if they felt that the client’s choice style was unflattering. Gimlin believed that these stylists saw beauty standards as universal, and on a scale from “bad” to “good,” while their upper-middle class clients’ style choices were grounded in their social group, and were concerned with “appropriateness.” While a certain style might be beautiful for a celebrity on a magazine, it was not appropriate for their lifestyles as middle-aged professionals and mothers [6].

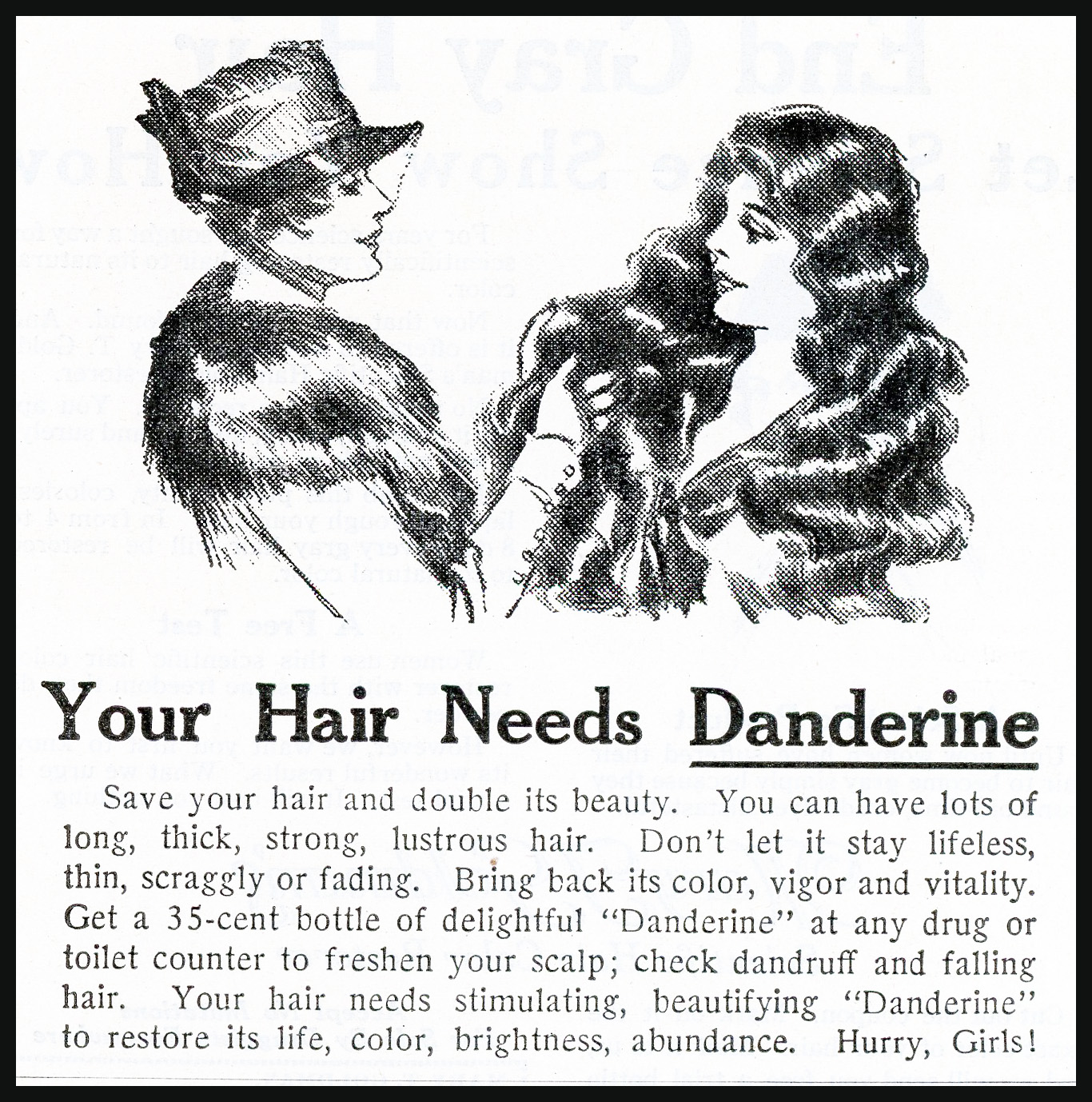

[Image 8]

Hair and Gender

Hair and Gender

Traditionally, western hairstyles for men and women are set in opposition to one another, as femininity and masculinity have been viewed as binaries. Women’s hair is longer, and styled more elaborately. Trends change often. A great deal of emphasis is put on optimizing youth and femininity, and disguising age. Men’s hair has changed considerably less during the past century; it is kept short, and less time is spent on daily styling. Men’s hairstyles have changed only more recently, influenced by the longer styles of the 1960s and 70s, the advent of the “metrosexual,” appearance-conscious man, and growing challenges to traditional masculine norms.

While men traditionally visited barbershops through the 1900s, several events such as the growth of white-collar jobs, and technological advances in hair care caused barbershops to fall in popularity [4], [18]. Barbering focused on the use of tools such as the straight razor and electric clipper to groom men’s head and facial hair. The invention of the safety razor led more men to shave at home. The entrance of women into the workforce introduced both more women hairdressers, and more women who visited those same hairdressers. Cosmetology embodied not only cutting, but dyeing, perming, conditioning, blow-drying, and so-forth. Salons and female hairdressers readily accepted the advances in technology while most barbershops did not, which contributed to their decline. By the 1970s, men’s hairstyles grew longer, requiring less cutting. “Once the uniform style for all men, the short back and sides became the preserve of older men and signified conservatism,” note Brookes and Smith, “The aging barber workforce found it difficult to accept the development of a youth culture with an emphasis on new styles that blurred the boundaries between masculine and feminine appearance” [18].

[Image 9]

While barbershops exist today, there are much fewer than there were a century ago. They are more often frequented by men who still desire the simple “short back and sides” cut. These spaces represent a resistance to time, as their technology and services have remained largely unchanged. They are almost exclusively men’s spaces catering to traditional ideals of men’s hair and men’s talk. In Lawson’s survey of barbershops, which varied in location and social class,

“All seventeen barbers said they disliked and would not style long hair, even if it was on men. They linked long hair to femininity and homosexuality, and bonded with clients about mutually articulating their dislike of ‘f*gs’” [4].

When asked about topics of conversation, one barber said, “We talk about business, what’s going on with companies in the area, whose business is in trouble, if they are selling it and so on. We discuss money and deal, guy stuff.” Many expressed discomfort about the idea of women entering the shop, though it was rare, because women also saw it as a men’s space. In Barber’s “The Well-Coiffed Man,” middle class professional men visited salons instead of barbers. “The men position themselves as ‘classy’ by comparing ‘salon talk’ to barbershop talk and by describing the barbershop as a place for the expression of working-class masculinity in which men talk about ‘beer and p*ssy,’ sports and cars” [6].

While the stereotype about barbershops as overly-masculinized, misogynistic spaces may not be true in all cases, it seems that both the people who work at or frequent barbershops, and those who do not, have a concept of what the space is, and position their identities accordingly. Barbershop clients affirm their version of masculinity, while male salon clients reject it for a “classier” masculine ideal. Despite seeing themselves above the hegemonic masculine culture, male clients at salons dealt with their own internal conflict in affirming their masculinity. They acknowledged that salons were feminized spaces, and expressed wishes for televisions showing sports, and GQ or Esquire magazines in addition to the women’s magazine in the waiting area. (Note the target demographic for those magazines is very different from Guns and Ammo, or Ebony. These men are positioning themselves as both middle-class and white) [6].

These men also noted that the female stylist’s touch was a more pleasurable experience than a barber’s, and that they would not enjoy having their hair washed and scalps massaged the same way if they were at a barber. This can be interpreted as an implicitly homophobic feeling that enjoying a woman’s touch is acceptable, but enjoying another man’s touch is not. Note that the men who go to barbers affirm their masculinity by having their hair done by fellow men, but the men who go to salons would prefer to be styled by a woman because a male stylist might challenge the client’s sense of masculinity. Touch is intimate, but it can be interpreted as pleasurable and therapeutic, as an indicator of trust and community, or as a purely necessary component of having one’s hair cut, the intimacy ignored or repressed.

Despite cosmetology’s stereotype as women’s work, more men are entering the field. They often see advantages due to their gender. Even in feminized spaces, men are viewed as being more knowledgeable and skillful [4], [13], [18]. The most popular and successful stylists are men. It seems that because they are men in feminized spaces, people interpret them as unique, and therefore gifted or more serious in their work. Many women express preference for a male stylist. Similar to the men who enjoy the touch and care of their female stylists, women feel their femininity and beauty is affirmed by a handsome man who flirts and jokes with them, and who makes them feel beautiful.

The men who work in salons face their own needs to simultaneously fit into a feminized culture, yet affirm their masculinity to themselves and their peers. They acknowledge that they take on a certain personality when at work, acting more feminine or “campy,” as some put it, and say that they enjoy the company of their female coworkers and clients [13]. In many ways, they reject hegemonic masculinity. However, they make it a point to show that they engage in traditionally masculine activities such as fixing their cars when outside of the salon. Some heterosexual male stylists said they are often mistaken as homosexual when people learn of their profession, and expressed annoyance or frustration about this [13]. Therefore, these men continue to reflect society’s ideas of hair styling as primarily women’s work, and find ways to affirm their concepts of masculinity and heterosexuality within and outside of salons.

[Image 10] Manly men doing manly man things.

Because hair styling spaces are intensely embedded with messages of gender, class, and race, they become locations of enculturation for the children who are present. The physical enviroment as well as gendered talk affect the children’s ideas of group identity. In “Working on Hair,” a six-year-old boy accompanying his mother at a hair salon called the male stylist a “barber,” explaining,

“He is a barber because he is a man and he cuts hair. I think it would be fun to be a barber when I grow up, but I would only like to cut men’s hair because I do not want to touch girls. No girls get their hair cut where my dad takes me” [4].

Another boy from the same study said, “the barbershop is the best place for boys to be.” One girl said of her mother’s salon, “I learn girl stuff. I want a Braun [butane-fired] hot comb for Christmas. I want my hair dyed blonde when my mom says I’m old enough” [4].

In contrast, these spaces can also work to shift children’s gender ideas away from the traditional norm. One boy said of the salon he was in,

“My mom says she has taken me here since I was three years old. I have never been to a barber. I like the way Frank cuts my hair. My mom and dad say barbers do not cut hair as good. Frank cuts my dad’s and brother’s hair too” [4].

Clearly, the spaces that parents choose affect their children’s view. Some are taught that only barbers can cut men’s hair, while others are taught that they do not provide an appropriate style. The relationships that the children have with their family’s stylists begin at a young age.

[Image 11]

In “Fading, Twisting, Weaving,” Bryant Keith Alexander reminisced on his childhood experience visiting the neighborhood barber. He and his brothers dreaded it because the barber knew that their father wanted close, nearly clean-shaven cuts for all of them despite however much they begged for “just a little off the top.” His father had set down expectations of appearance for them. He later describes his experiences visiting both the men’s and women’s sides of another shop; the barbershop for when he kept his hair short, and the salon when he had his hair in locs. He noted that as a Black gay man, he stood somewhere in between, as the nature of talk on either side both welcomed and excluded him. The men’s talk of the barbershop affirmed traditional masculinity, and the women talked about men, and the struggles of being a wife and mother. Both sides were “marked by heterosexual discourse” [11]. As with other reports of men in feminized spaces, he felt welcomed by the women, but wondered if this welcoming was a sign of being seen as an “honorary woman,” a de-masculinized man.

Client Stylist Relationships and Conclusion

Client and Stylist Relationships

Stylists are very aware of the emotional aspect of their work. While some see it as a burden, most find satisfaction in it. As noted in the studies of Black barbershops, stylists often see themselves in an influential role, and willingly take on the part.

In “Look Good, Feel Better,” the authors refer to workers who provide beauty services as “beauty therapists” [9]. This category is not limited to hair dressing alone, and can include those who provide massages, facials, manicures, waxing, and so forth. The beauty therapists in the study drew parallels between their work and the work of healthcare professionals; they did not see themselves as simply providing beauty services, but rather doing work that helped to alleviate stress and to increase self-esteem. The clients’ emotions were an integral part of the work. The beauty therapists defined their occupation in terms of work with both feelings and the body, and referred to their services (hair styling, manicures, massage, etc) as “treatments.” In contrast to the stylists in “Pamela’s Place,” the beauty therapists in “Look Good, Feel Better,” did not see themselves as part of the industry that placed unobtainable standards of beauty on women. They did not believe that they pushed those standards on their clients. They saw their service as a way to help women become happier with themselves through beauty work, thus affirming the clients in their identities.

[Image 12] Touch creates intimacy and fosters community.

Despite the emotional component of working with bodies, stylists receive little to no formal training in emotional labor, and it is often seen as a “natural” part of being a woman, rather than a professional skill. Even the beauty therapists in “Look Good, Feel Better” saw it as something a person simply had a knack for, or a skill developed over time. Because the process and products of emotional labor are not tangible, and because it has long been an assumed part of certain industries– especially those dominated by women, it is too often overlooked as a real component that demands skill and affects a business’s success. Recently, more and more people in fields that deal with customers’ emotions are demanding that this component of their work be recognized officially in job descriptions, training, and fair pay. Emotional labor is being recognized as actual work rather than an expected trait of female workers.

In a hair styling space, the effect of the stylist/client relationship on the client’s identity is two-fold: First, the stylist provides a service that helps the client achieve an outward appearance that agrees with their identity. Second, the stylist and client establish a relationship that is focused on the client’s emotional needs and affirms their feelings about themselves. While the relationship can be emotionally intimate, it is focused on the client. There is no requirement for the client to reciprocate identity-affirming talk to the stylist. Whether or not this connection is genuine on the part of the stylist does not seem to have an effect, as long as the client feels it is genuine. Even if the client is aware that emotional labor is part of the stylist’s job, even a transient illusion of being cared for is often enough. This goes back to the intimate and communal nature of touch and talk. For example, a woman may enjoy the touch and playful flirting from a male stylist whom she knows to be homosexual; even though she is aware that he is not sexually attracted to her, she still enjoys the feeling of attention from a man.

The topics of discussion do not necessarily have to be deeply personal. Men in barbershops would most likely deny any therapy-like talk. However, discussing common interests such as sports, business, and cars works to affirm the men’s ideas of themselves, and forms a community of shared masculinity. These are spaces in which “men can be men,” or “women can be women,” suggesting that gendered spaces offer a unique respite from daily interactions with the other gender. This can be positive and identity-confirming, or, as described earlier, can be seen as implicit indoctrination into societal norms.

[Image 13]

Conclusion

A person chooses their hairstyle based on their ideas of their personal identity, and of their identity within social groups. As hair is a very public indicator of identity, people are aware that their hair transmits messages about themselves to those around them. The act of doing hair is deeply personal and ritualistic, as it involves groups of people engaging in touch and talk. Through this intimate relationship, a client and stylist communicate, negotiate, construct, and affirm the client’s identity.

Hair styling spaces are centers of cultural discourse, where members of the same social groups validate each other and share information. They engage in talk that affirms their group identities. Oftentimes, this talk compares the group with other groups seen to be opposite. In masculine spaces, members discuss sports, money, sex, and other topics that affirm traditional masculinity. In middle-class and upper-middle-class spaces, clients express their needs to be seen as professional and stylish, but not “tacky,” or “old-fashioned.” In Black spaces, older members of the community instill knowledge and encouragement to younger members, teaching them what it means to be Black men or women. For children, hair styling spaces become part of their process of enculturation, influencing their ideas of gender, class, and race at a young age.

Clients use their stylists as confidants and informal therapists, often divulging deeply personal information. Emotional labor is seen as a natural part of beauty work, and stylists acknowledge that the success of their business relies not only on the quality of their services but also the personal connection. For some stylists, these relationships are genuine and contribute to their sense of satisfaction. For others, it is a source of stress.

Hair, identity, and social grooming are such complex phenomena that this article barely skims the surface. Future articles will explore individual components, such as: the politics of hair in times of social change; hair rituals marking transitions and rites of passage; and race and ideal beauty. Stay tuned for more explorations into the individual, social, and symbolic nature of hair.

References

References

[1] Synnott, Anthony. “Shame and glory: A sociology of hair.” The British journal of sociology 38, no. 3 (1987): 381-413.

[2] Hallpike, Christopher R. “Social hair.” Man 4, no. 2 (1969): 256-264.

[3] Leach, Edmund Ronald. “Magical hair.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 88, no. 2 (1958): 147-164.

[4] Lawson, Helene M. “Working on hair.” Qualitative Sociology 22, no. 3 (1999): 235-257.

[5] Hirschman, Elizabeth C. “Hair as attribute, hair as symbol, hair as self.” GCB-‐Gender and Consumer (2002).

[6] Barber, Kristen. “The well-coiffed man: Class, race, and heterosexual masculinity in the hair salon.” Gender & Society 22, no. 4 (2008): 455-476.

[7] Gimlin, Debra. “Pamela’s place: Power and negotiation in the hair salon.” Gender & Society 10, no. 5 (1996): 505-526.

[8] Toerien, Merran, and Celia Kitzinger. “Emotional labour in action: Navigating multiple involvements in the beauty salon.” Sociology 41, no. 4 (2007): 645-662.

[9] Sharma, Ursula, and Paula Black. “Look good, feel better: beauty therapy as emotional labour.” Sociology 35, no. 4 (2001): 913-931.

[10] Shabazz, David L. “Barbershops as cultural forums for African American males.” Journal of Black Studies 47, no. 4 (2016): 295-312.

[11] Alexander, Bryant Keith. “Fading, twisting, and weaving: An interpretive ethnography of the Black barbershop as cultural space.” Qualitative Inquiry 9, no. 1 (2003): 105-128.

[12] Marberry, Craig. Cuttin’up: Wit and wisdom from black barber shops. Doubleday Books, 2005.

[13]Robinson, Victoria, Alexandra Hall, and Jenny Hockey. “Masculinities, sexualities, and the limits of subversion: Being a man in hairdressing.” Men and masculinities 14, no. 1 (2011): 31-50.

[14] Ahmed, SM Faizan. “Making beautiful: Male workers in beauty parlors.” Men and Masculinities 9, no. 2 (2006): 168-185.

[15] Mills, Quincy T. ““I’ve Got Something to Say”: The Public Square, Public Discourse, and the Barbershop.” Radical History Review 2005, no. 93 (2005): 192-199.

[16] Harris-Lacewell, Melissa, and Quincy T. Mills. “Truth and soul: Black talk in the barbershop.” Barbershops, Bibles, and BET (2004): 162-302.

[17] Franklin, Clyde W. “The Black male urban barbershop as a sex-role socialization setting.” Sex Roles 12, no. 9-10 (1985): 965-979.

[18] Brookes, Barbara, and Catherine Smith. “Technology and gender: barbers and hairdressers in New Zealand, 1900–1970.” History and Technology 25, no. 4 (2009): 365-386.

Images

[Image 1] Left: Original photograph of African-American siblings from family album in Philadelphia area, est. mid 1920s, USA, private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD image collection

Right: Original postcard, “Won’t Mama Be Pleased!” 1920s, USA, private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 2] © 2008 Alex Morgan for TAAB conference, Shrewsbury, UK, from photograph of young Japanese woman with lacquered, styled, hair, 1920s.

[Image 3] © 2008 Alex Morgan for TAAB conference, Shrewsbury, UK, from photograph by Lehnert & Landrok, North Africa, 1904 – 1914

[Image 4] Photographic postcard, Belgian, early 20th c., private collection Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 5] Original studio photograph of African-American man, 1920’s, from family album in Philadelphia area, private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 6] Original studio photograph of African-American man in zoot suit, 1940s, private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 7] © 2008 Alex Morgan for TAAB conference, Shrewsbury, UK, from original photograph of a woman in Pittsburgh, PA, wearing male clothing, 1940s.

[Image 8] Danderine advertisement from magazine, 1920s, USA, private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 9] © 2008 Alex Morgan for TAAB conference, Shrewsbury, UK, from studio photograph of two young men, Boston area, USA, 1920s.

[Image 10] Informal snapshot of men’s bodybuilding competition, 1970s USA, private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 11] Postcard of cat cartoons by Eugen Hartung, 1950s, published by Alfred Mainzer Inc., private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 12] V34189, “A Beauty Parlor in the Island of Zanzibar, Africa. The Swahil Women Take Great Pains with Their Hair.” Stereoscope card by Keystone View Company, early 20th , private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD

[Image 13] Postcard, early 20th century, “I’m almost ready,” private collection of Catherine Cartwright-Jones PhD